Drawing on his new book about George Little, Peter Wakelin writes about the artist’s life-long commitment to recording urban and industrial landscapes.

George Little wrote in 2004: ‘Everywhere the images of my choice are disappearing: pithead wheels, slag heaps, heavy industry, the fishing industry, even the streets of workers’ houses, and the Swansea docks as I knew them are virtually no more … my subject matter is almost a memory.’

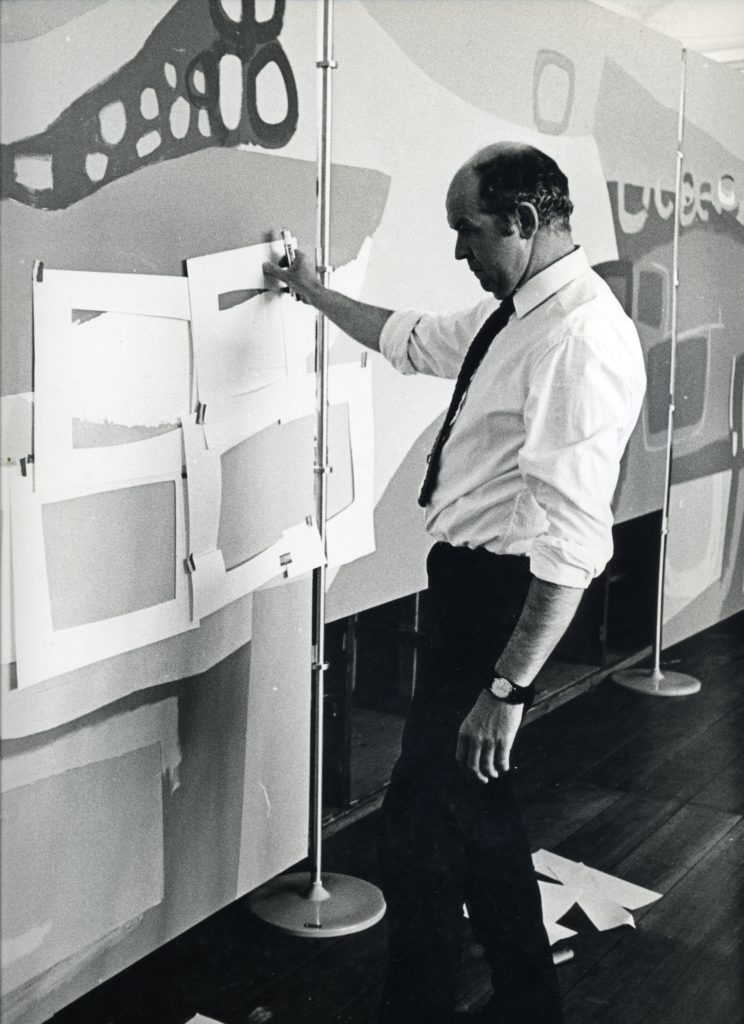

Born in the east end of Swansea in 1927, George Little grew up next to the abandoned copper works, slag heaps and still-busy docks of Dylan Thomas’s ‘ugly, lovely town’. As a teenager the destruction of the Swansea Blitz was seared into his imagination. He trained at Swansea College of Art and the Ruskin School of Drawing in Oxford and taught art history at Swansea University.

Heavy industry and the gaunt aftermath of deindustrialisation generally inspire horror or repulsion, but for those with the eyes to see them differently, such environments are compelling. Generations of artists have been drawn to them, as have writers, filmmakers, designers, archaeologists and urban explorers.

Sites of working industry have a compelling scale, visual complexity and mystique. And where industry has ebbed away, distress and dereliction have often left behind a beauty in the sad grandeur of decay or the miracle of natural regeneration.

No artist has been more committed to interpreting industrial and ex-industrial environments than George Little. Born in the east end of Swansea in the lead-up to the Great Depression, he spent his long life exploring the nearby docks, bomb sites, abandoned copper smelters and left-behind streets.

He captured these environments in paintings, drawings, collages and photographs from the late 1940s to his death in 2017. He also sought parallels elsewhere: in the South Wales coalfield, Anglesey, South Yorkshire, and as far afield as Berlin and New York.

Fascination with ruins is an artistic tradition that goes back to the eighteenth century, when poets and painters sought bare ruined choirs and ivy-clad castles as objects of aesthetic interest and symbols of transitory existence, as when Turner painted the overgrown nave at Tintern Abbey and Shelley imagined the broken statue of forgotten ruler Ozymandias.

Artists who discovered valid themes in the overwhelming power embodied in sea-cliffs, waterfalls and mountains found similarly ‘sublime’ qualities in the mines, mills and furnaces of the industrial revolution, which split open the earth, built vast structures or transformed rock to white-hot metal.

In the early twentieth century, the subjects of industry and ruination coalesced as traditional and heavy industrial sectors contracted and dragged dependent communities with them. The Second World War made further wounds. That was followed by long processes of deindustrialisation, urban decay and serial renewal.

George allied himself with artists of the preceding generation who sought to comment on this changing world like John Piper and Graham Sutherland: modernists interested in abstract forms, surreal connotations and expressive colours.

George liked to quote another of those painters, Prunella Clough: ‘It helps perhaps that so much of the industrial material is already abstract.’ He saw in his subjects not just patterns, colours and textures but strange, ambiguous forms, associations and moods.

Interest in the visual legacy of run-down towns and derelict industrial sites still grows. They are backdrops in photoshoots for fashion magazines and album covers, filming locations for thrillers and post-apocalyptic horror, and prime subjects for photographers and painters, who hunt the grandeur of decay across the world, from deserted Chernobyl to abandoned car plants in Detroit.

George found this material on his own doorstep. The docks of Swansea in his youth still teemed with rail lines and cargo ships framed by the verticals of coal hoists and cranes.

The centre of the town was bombed flat before his eyes in 1941. And the four miles of valley above the mouth of the River Tawe, once known as ‘Copperopolis’ and packed with smelting and manufacturing works, was being abandoned site by site.

In that space of valley, the German writer Peter Sager noted in the Pallas guide to Wales, ‘there were no less than 150 metal-processing works in 1890. Half a century later, this area of 1,200 acres had become the biggest industrial wasteland in the whole of Britain.’

There is much to be learned from George’s long project to interpret these legacies. He was never nostalgic about past industry or its effects. He knew the suffering that mining and smelting had brought, and he appreciated that the colours in the slag that so excited him were the poisonous residues of arsenic, copper, iron, tin, lead, zinc, cadmium and nickel.

He was glad of reclamation and the return of grass and trees, provided some reminders of the industrial inheritance remained.

He liked to say that all his work was ‘based on facts’ he found in his environment. But he transformed those facts of colour, form and texture, bringing his own response to bear on them.

He found both pity and dignity in his subjects, whether the docks when they were busy or the later detritus of quays left to weeds and rust, polluted waste tips, half-ruined works, run-down streets of workers’ settlements or the wasteland of the lulled and bombed-out town. His compositions brought redemption where it might be least expected.

The ‘ugly, lovely’ oxymoron coined by Dylan Thomas captured simultaneously the warmth of his and George Little’s hometown on its glistening bay and the sadness of its industrial decline and scruffy irregularity. George found a visual language to restate the contradiction. He did something extraordinary in his expression of the place.

As his friend, the historian Prys Morgan, wrote in 2017, he transformed its ugliness into ‘memorably lovely paintings’.

George Little: The Ugly Lovely Landscape by Peter Wakelin is available direct from Parthian or at a launch event at Tabernacle Church, Mumbles, at 7pm on 16 November. It is also available from all good bookshops.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.