I’m not really ready to think about a world without David Lynch yet. But I have at least realised in the days since his passing that Lynch was probably my introduction to genuine art – art which I felt like I was part of the genuine audience for. This came with Twin Peaks, which I first watched, terrified and confused and thrilled and delighted, when I was 12. My mental life was massively expanded by that show. I was that kid at school brushing my hair like Cooper – back when I had hair! – and walking around talking into a TV remote like it was a dictaphone and really trying to like coffee. (I was eventually successful on that front.) What an idiot I was, and yet Cooper, I still feel, is an extremely good role model. Pretty much ideal, really.

Anyway, over the last few days a lot of people have been thinking about Lynch in relationship to video games, and that feels like at least a tiny way into considering a world without him. There’s the PS2 ads he made, of course, and there’s all the people he influenced – explicitly, like Remedy, and implicitly like… well, I have my suspicions.

All that is great, but what I want to talk about today is a moment from the movie David Lynch: The Art Life, which a dear friend suggested I watch this week. It’s a documentary about Lynch’s life, his memory of his childhood and his endless project of creating art – just by living, it sometimes seems. My friend said it was the only time he’d ever seen Lynch as he truly was. It’s a documentary but it feels like we’re seeing Lynch as he is when he’s all by himself.

It’s a completely fascinating movie – it’s beautiful, to use a word that Lynch himself was very fond of. And there’s this magical moment that I’ve rewatched about four times so far. Lynch is talking about his idyllic childhood in the late 40s, early 50s. What did he like to do more than anything? He liked to sit in a hole dug under a tree with his best friend. His dad would partly fill the hole with water from a hose so there was mud to play with. Lynch’s verdict? “Forget it!“

My dad belongs to the same generation as Lynch, and so I understood that “forget it”. It meant that there was no higher compliment available, that his joy was fairly topped out. Sitting in the mud with your pal, squishing the mud, the way that Lynch, a noble old fellow in his studio in LA, squeezes something disgusting and beautiful onto the piece of bronzed wood he’s using as a canvas. Sunlight. Open skies. This is living. Friends, a mood, sensation: forget it.

When I think of my own “forget it” moments – and inevitably I think about them in games as much as in life – they’re often quite similar to what Lynch was remembering. They don’t involve mud and holes, but they involve fun for its own sake, and fun that creates a moment, that encourages you to stay, regardless of progress, or ticking things off in a quest line or anything like that.

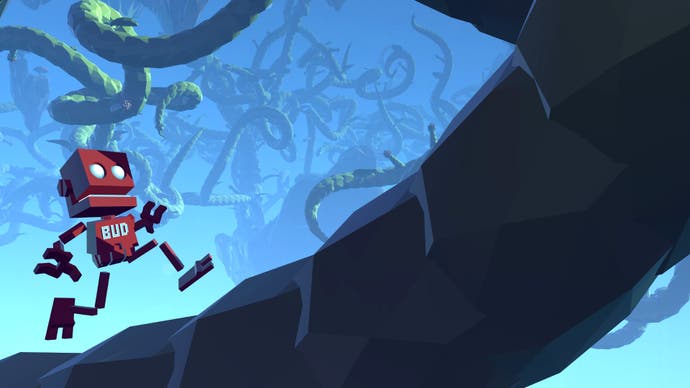

I’m thinking of the same games I always bang on about inevitably – climbing and falling in Grow Home, jumping between buildings in Crackdown, finding a new path or stopping in a glade in A Short Hike. Yep, my same old nonsense, but that’s the point. Lynch’s art, while frequently scary, is filled with pleasures, and they’re the pleasures of being immersed in a world that feels comprehensive, and which has the playful details to prove it. The murder mystery, but also the cherry pie and coffee.

You start to see this everywhere in Lynch, this thing that I in turn value most in games: experience for the sake of it, experience that’s undirected but deeply compelling and often joyous. It must be fostered, protected. As Lynch hacks a multimedia work together in modern LA, bending wire into handwritten words and then getting endearingly frustrated when he can’t drill them into the panel he has in mind – “Motherf***er!” – he talks about how his mother knew that he loved to draw and then made sure that he was never allowed colouring books. “A beautiful thing came to her,” he says – that word again. “They would be restrictive and kill creativity.” Testify!

A few last quotes that fill me with different kinds of enthusiasms for creative works like movies and like paintings and like video games. In his childhood, Lynch was not allowed to wander far from home, although certainly further than most kids are allowed today. “My life was no bigger than a couple of blocks,” he says. Sounds small? Not to a kid. “Huge worlds were in those two blocks. Huge worlds.” Look closely, I think he’s saying. Look clearly. There is wonder all around you. There is potential – possibility space, and I’m probably misusing that term but whatever – in all directions.

And surrealism. More specifically what surrealism is often for. This isn’t in the documentary, but when I think of Lynch and games, rather than remembring his PS2 ad, I think of something he said in an interview once. I haven’t even tried to look for the precise quote just now, because the wording in my memory is perfect – I can hear it in his shaking, defiant, Jimmy Stewart voice: “Every Christmas,” he said, always speaking as if he was enunciating vital travel instructions into a telephone and down a very crackly line, “every Christmas we got a gun.”

He was talking about childhood again, and that peculiar Americana that he tapped so beautifully and weirdly in so many of his films and TV shows. Christmas morning rendered stuttering and gauzy in cinefilm, boxes under the tree for the kids, and every time, one of those boxes would contain a toy gun. Hooray!

I think of this quote a lot, and it’s because for me it gets deep into Lynch’s work, it gets through it and out the other side, in fact, and back into our world. Lynch was a surrealist, sure, but a lot of surrealism is about making people question the bizarre things in their own lives that they take for granted and which they maybe should look at a bit more. In other words, and this is by no means an original thought, a lot of the impact of his work was grounded in realism.

And maybe he saw the real world more clearly than a lot of us. Every Christmas I got a gun. What an absolutely bizarre sentence, and yet how much more bizarre that it’s true. 50s kids played with toy guns. And probably not just 50s kids. My parents never allowed toy guns in the house, but I have a vivid memory of my brother one morning eating a piece of toast strategically until it looked like a gun and then shooting me with it. Wild.

So yes, that quote makes me feel like I’ve properly opened my eyes to something very strange about a lot of us, something that’s always been there, and that I haven’t seen clearly because it’s always been there. From here I could segue to the fact that I’ve always just accepted that lots of games involve guns and shooting when guns and shooting aren’t things I’m particularly keen on in other parts of my life. But that feels a bit too obvious. Instead, it makes me want to try to think like Lynch a bit more – to look at the things in life, and by extension, the things that you often get in games, the kinds of things that seem to creep into games without anyone explicitly planning for them, and try to see them more clearly – see them for their easy unforced surrealism, see them afresh and see how weird they are.

(This stuff is serious, too, particularly for Lynch. There was a lot of fun and a lot of joy in his movies, but I had a brilliant chat with a game developer a while back who made a very persuasive case that Twin Peaks’ third season was a perfect depiction of the way that late capitalism had hollowed out entire communities and made a way of life impossible. I had missed it, with all the pie and coffee and donuts but it changes things completely.)

Last quote, and this has been doing the rounds recently on TikTok and other places. It’s Lynch talking about how he made films that involved suffering but he didn’t want his collaborators to suffer while making them. He wanted a pleasant set. He wanted, he said, to “get more happiness in the doing.” What a simple thought – and how beautiful! A reminder, perhaps, to pick and choose in art, in games, and foreground the stuff that makes the moment vivid and worthwhile.

Thank you for everything, David Lynch.