Shanghai’s five-year “Our Water” cultural exchange campaign kicked up a gear in April with the opening of acclaimed ink painting artist Chen Jialing’s first exhibition in Paris, France.

“Chen Jialing: Une Vie au Bord du Fleuve” (A Life by the River), which runs until April 21 at the city’s Réfectoire des Cordelier, is a major feature of Our Water: Flowing From Shanghai — Intercultural Dialogues Among World Cities, an international platform to promote urban cultural exchanges and cooperation. The event also coincides with the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France.

Born in 1937, Chen is an artist and professor at the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts whose unique style blends traditional and modern, and oriental and Western artistic elements. He studied under Chinese ink painting masters such as Pan Tianshou and Lu Yanshao, and works in various formats, including wood prints, ceramics, furniture, and textiles.

Here, Chen and curator Cao Dan discuss the exhibition and the deep cultural roots connecting China and France.

The Paper: What were the inspirations and curatorial ideas behind “Une Vie au Bord du Fleuve”? What do you hope audiences will pay particular attention to?

Chen: Water provides very beautiful imagery, symbolizing beauty and purity. I believe that French audiences will like it. I have painted the “10 Scenes of West Lake,” as well as other famous rivers and mountains, such as those in Guilin (in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region) and Huangshan Mountain (in Anhui province). Ink painting is able to capture the unique charm of the Chinese landscape.

To show its diversity, the exhibition also features porcelain works, which many French people have shown a fondness for. I’ve made a new attempt to combine porcelain with ink painting, designing a series of works that include porcelain plates, arrow quivers, and vats.

The arrow quivers are my early works, while the porcelain plates have been specially created for this exhibition in France. I chose the iris, the national flower of France, as the decorative pattern, which I believe the French will love. I also incorporated the lotus, which has a deep meaning in Chinese culture. Together with the iris, it forms a bridge between Chinese and Western cultures.

The exhibition aims to be a breakthrough in porcelain technology. I hoped that by mastering heat control, my porcelain could embody properties that lie somewhere between porcelain and pottery. After many trials, I was finally able to do so, creating pieces that have the hardness of porcelain and the simplicity of pottery. By doing this, I have demonstrated my wish that the friendship between France and China will have the strength of porcelain and the sincerity of pottery.

The exhibition also includes three large vats, one of which is 1.8 meters in diameter. The larger the diameter of the vat, the more difficult it is to forge. I made two iris vats and one pomegranate vat. The red pomegranate represents fruitfulness, unity, and love, while the iris represents our goodwill and friendship toward the French people. These vats are not only a continuous pursuit of artistic creation but also a demonstration of the modernization of Chinese industrial and handicraft ceramics.

Cao: We chose a giant space in France as the exhibition venue (Le Réfectoire des Cordelier), which embodies strong elements of Western religion. During the preparation process, we decided to enrich the space with large-sized works to stunning effect. For example, there are numerous pillars in the exhibition space, and we have skillfully utilized them to distribute the paintings in different areas.

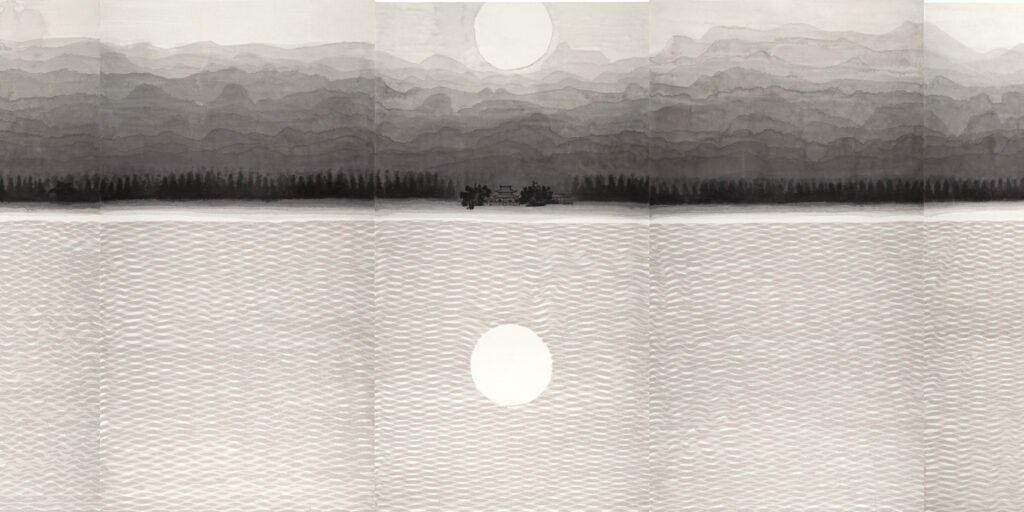

When the theme of “Une Vie au Bord du Fleuve” was decided, we discussed how to create works around the element of water. Chen created a new batch of ink paintings based on his original works. These paintings have been inspired by Chinese landscapes, and most of the large-sized paintings are in black and white. Chen’s art is characterized by his exquisite mastery of ink and wash, especially the layering of ink, to create rich layers and special effects. His works have the flavor of traditional Chinese ink painting, with some elements of Western abstract art blended in. I believe that Western visitors will feel the unique artistic charm in his works.

In addition, we interviewed Chen for a 10-minute documentary, which will be shown at the exhibition together with “Chen Jialing,” a documentary directed by Jia Zhangke, to give the French people a comprehensive understanding of his life and artistic creations.

We will also organize a series of activities for children and the public, and invite them to try their hand at drawing with Chinese brushes on rice paper. In addition, French sinologists will share their insights on Chinese painting. What’s more, Eric Lefebvre, the director of the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, will serve as an academic advisor and lead a discussion with Chen during the exhibition.

The Paper: What’s the meaning behind the exhibition’s theme, “Une Vie au Bord du Fleuve”?

Chen: The curation originated from the cooperation between the French team and Shanghai International Culture Association, with the aim of celebrating the 60th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and France. Though the preparation time for the exhibition was tight, the team worked hard to present the splendor of the two countries’ waterfront cultures. The theme “Une Vie au Bord du Fleuve” was chosen because, on one hand, water is the source of life, which has universal and global significance. On the other hand, water symbolizes goodness and harmony in Chinese culture.

The Seine River in Paris and Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek and Huangpu River are important channels for cultural exchange between the two countries. The team wanted me to create water-based landscape paintings in the form of ink paintings to show the friendly bonds between the Chinese and the French.

The Paper: What do you feel is the relationship between rivers and art in the cities of Shanghai and Paris?

Cao: Rivers are closely related to human civilization and the history of cities. A river is a city’s soul. Shanghai and Paris are both fashionable and cosmopolitan cities, attracting many literary figures and artists. Shanghai is a center of the arts, and it has birthed the “Shanghai style.” Many art museums are located along the Huangpu River and Suzhou Creek. Though the rivers in Paris and Shanghai are different, they are both important features from which energy flows.

Rivers used to be the main means of transportation; their banks were lined with factories and warehouses, as well as the homes of dockworkers and sailors. As urbanization progressed, factories and transportation gradually moved away, leaving behind only fading memories and old photographs.

Chen is an outstanding artist who carries the past to the present. He has inherited the traditional essence of the older generation of Chinese ink artists, and at the same time has innovated and developed his artistic skills. Overseas art has influenced his artistic creation, especially his experiences living in Europe, where he was inspired by modern artists such as Gauguin and Cézanne. His works are a fusion of traditional ink and contemporary visual art, creating a unique artistic style.

Artistic exchanges between Shanghai and Paris are not rare. In fact, the Chinese artworks that Chen saw at the Musée Guimet in Paris had a profound impact on him, making him realize that Chinese art has a unique charm. Inspired by his teacher, Lu Yanshao, he realized that art creation should be free and joyful, without constraints.

The Paper: What’s your understanding of the common cultural bonds between China and France?

Chen: The development of Chinese modern art has deep roots in France. The earliest art school in Shanghai was founded by Liu Haisu, who was deeply influenced by his studies in France. Xu Beihong and other artists who studied in France also played an important role in the art education system after the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

My own art career has been impacted by French education, too. Lin Fengmian, as an early bridge between Chinese and foreign art education, played a key role in founding the National Academy of Fine Arts (China Academy of Art). Lin was one of the artists who stayed in France, and his artistic philosophy had a profound impact on China’s art education.

China and France also have deep roots from a political point of view. For instance, former Chinese leaders Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping both studied in France. This political affiliation has further deepened the exchange and cooperation between China and France in various fields.

Actually, China has an intangible relationship with France in politics, arts, and the humanities. The relationship is both intentional and unintentional. We hope that through joint efforts, we can set a new benchmark of friendship and promote further exchanges and cooperation between China and France.

The Paper: What are your expectations for the collision between traditional Chinese art philosophy and French culture?

Chen: From the perspective of human nature, people’s pursuits are similar no matter whether they’re in the East or the West: the desire for freedom, the pursuit of a better life, and the desire for romantic and emotional fulfillment. This common ground makes us find resonance and seek understanding.

Historically, the West started to pay attention to the needs of human nature during the Renaissance, while China began to awaken after the May Fourth Movement in 1919. The great depth and richness of Chinese culture has given us a unique perspective on human nature, which also makes us express ourselves in a unique way. Concepts of peace, freedom, equality, and fraternity are in line with the needs of Chinese civilization.

As a form of expression, art is constantly advancing. The endless efforts of several generations have led to the remarkable achievements of today’s Chinese art.

A version of this article originally appeared in The Paper. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and is republished here with permission.

Translator: Eunice Ouyang; editors: Xue Ni and Hao Qibao.

Sponsored content by Sixth Tone × Our Water

(Header image: Details of “Autumn Moon on a Peaceful Lake,” 2024. Courtesy of Chen Jialing and the Doors Art and Culture Agency)