African-American artist Faith Ringgold died on April 13, 2024, at her home in Englewood, New Jersey. She was 93.

At a time when the possibilities for African-American women and female artists were almost nonexistent in the US in general and in the art world in particular, Faith Ringgold developed a remarkable oeuvre with originality, strength, coherence and relevance over five decades. Her work was born out of a visceral need to be an artist, to be able to create art and make it visible to the broadest audiences. It was also born out of her reasoned need to be a liberated and independent woman. It reflects both the realities of her life as an African-American artist from the neighbourhood of Harlem, in New York, where she maintained a home her whole life, and the political and social context in which it was created, in the United States from the 1960s until today. What sets Ringgold apart is the way she managed to merge her art and her life, her artistic and political commitments.

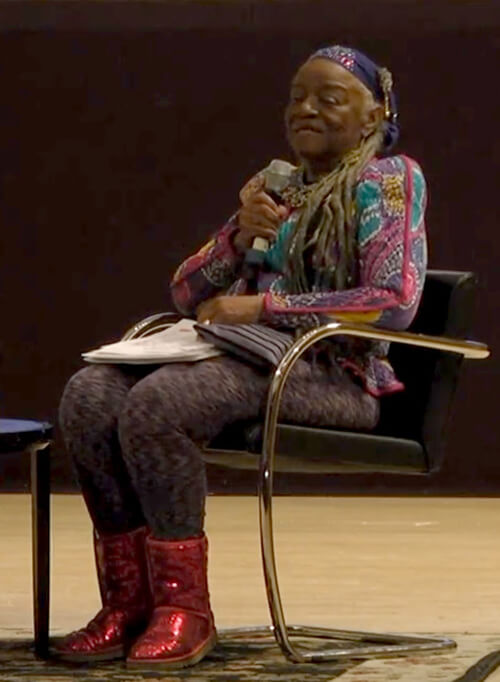

Like Louise Bourgeois and countless women in art history, Ringgold’s work received its due institutional recognition in the very last decade of her life. I discovered her work in the late 2000s when the MoMA exhibited her masterpiece American People Series #20: Die, 1967 (acquired in 2016). I met her in New York in 2022, when I invited her to present her first solo exhibition in France, at the Picasso Museum. She was an extremely admirable woman, intelligent, strong, warm and generous. She was also impressively beautiful, dashing and well-dressed, even in her 90s. Reading her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge: The Memoirs of Faith Ringgold (originally published in 1995), should be mandatory as her story is truly inspiring. A daughter, a sister, a wife, a mother and an educator before she could be an artist, her life and work are continuously intertwined. Her tenacity is matched only by the quality and coherence of all of her works.

Ringgold’s first paintings from the early 1960s, including Early Works and American People Series, to the 1971 mural For the Women’s House, already contain many of her interests: Greek busts, modern art and—in particular—Cubism, African aesthetics and the tradition of masks, etc. They announced what would later appear in her work, namely re-readings of the history of modern and contemporary art at the time of Black Power and the “Black is Beautiful” slogan, followed by the feminist movement. From the beginning of her career, Ringgold strictly painted oils on canvas. At the beginning of the 1970s, she began inventing new artistic forms that were more suited to her needs: “Tanka [thangka] paintings”, posters, “murals”, “soft sculptures”, performances, quilts—paintings drawn, painted and written on colourful fabrics sewn into patchworks— and even children’s books. The plurality of her work makes it particularly remarkable. Regardless of the formats, she combined both artistic and artisanal materials and techniques, blended high and low culture, simultaneously invoked modernity and vernacular traditions and systematically ignored any hierarchies between her artistic formats. She created a resolutely popular aesthetic, with the desire to contribute to the advent of true African-American art.

Ringgold’s artistic project also became a political one. She started to represent everything she observed around her to immortalise what wasn’t represented in contemporary American society, as African Americans were systematically made invisible. In doing so, she told stories that made history, from a female and Black point of view. Her aim was more to experience the world rather than solely represent it and to show a collective experience rather than illustrate individual stories. By questioning art history and its canons as well as the very definition of the avant-garde and modernity, by appropriating African cultural heritage and by absorbing the most innovative and radical ideas of her time, Ringgold managed to create a unique artistic language and invented a truly African-American aesthetic.

At the beginning of a new decade, Ringgold transformed an innovative artistic format: the quilt. With Echoes of Harlem (1980), an important new chapter of her career began. With the quilts, she finally was able to fuse text, image and design. Denigrated because they were exclusively associated with women, Ringgold chose to work in quilts for their direct connection to the history of slavery in the United States, speaking to slaves’ matriarchal societal organisation and to their desire to preserve and transmit African heritage to their descendants. The sets of quilts entitled The French Collection (1991-94) are certainly Ringgold’s most famous works. They appear to be the culmination of all her formal and conceptual research and illustrate the maturity with which she was able to develop her style.

Created during an artist residency in the south of France, the 12 paintings that compose the series tell the story of a young African-American, Willia Marie Simone, who left the US in the 1920s to live in France, become an artist and participate in the modernist movement. This character was already mentioned in the early 1970s when Ringgold produced a series of performances. If it seems partly inspired by the life and aspirations of the artist, it was the stylist Mrs. Willi Posey, her mother, who served as her model. Through this deliberately fictional story, full of anecdotes and autobiographical, historical, philosophical and aesthetic references, Ringgold took up the work of the masters of Western painting, revisited art history to denounce its ethnic and sexual homogeneity and recalled the role played by people of African origin within modernity.

In one of these paintings, Le Café des Artistes: The French Collection Part II, #11 (1994), Simone holds in her hands the lecture she is giving to an impressive group of European and African-American artists, including six black women, seated at the terrace of a Parisian café about her “The Colored Woman’s Manifesto of Art and Politics”. She explains that she decided to become an artist in order to be free and declares: “We must speak, otherwise our ideas and ourselves will remain invisible and inaudible.” Ringgold will forever remain this founding, unique artist who paved the way for generations of artists, of women, of artists and women of colour and well beyond. As for me and my daughter, who wasn’t yet two years old when we met her, we will keep hearing her beautiful voice tell us: “You can fly.”