CHAPTER 16

RED BIRD, BLACK WALL

Rusty wing

A dead dark thing

Crows too loud now

When red bird sing

—“Red Bird”

“Whatever you do, do not wear those horrible pants,” Jo Harvey instructed Terry, looking him up and down. He grinned mischievously and made a resolution to wear the horrible pants, which were made of a striped mattress ticking material as uncomfortable as it was hideous. They’d just left dinner at a beautiful almost-house high up in the Hollywood Hills and were driving home in their battered Volkswagen Beetle. The lavish construction site was the unfinished home of an older couple, Dean Whitmore and Will Huffman, who were renovating and expanding their mansion, adding several additional rooms. Terry had been working for them since he’d completed his junior year at Chouinard, doing light construction, gardening, and handyman tasks. It was a solid, steady summer job that he’d found, like many of his gigs, on the Chouinard help wanted bulletin board. He and Jo Harvey were “absolutely busted” at this point, and a free dinner prepared by elders was like manna from heaven.

A week earlier, Terry had been standing around in Dean and Will’s living room waiting for Dean to cut cheques for him and a few other straggling workers. Restless and bone-tired, he noticed a piano in the corner of the room, traced his fingers down the keys, looked around, and sat down. He was one of the last labourers left that day, and his employers were out of sight, so there wasn’t anyone to bother. Anyway, in his limited interactions with them, the mansion’s owners had always seemed kind, if a bit distant. An out gay couple, especially a middle-aged one (Dean was 43 at the time), was certainly still an astonishing novelty to someone who had grown up in Lubbock. But Terry’s time at Chouinard had opened his mind and dismantled his prejudices about other people’s private lives and choices of sexual partners, which he figured were not any of his damn business. “What the hell,” he thought, and pressed his fingers onto the keys experimentally, letting a few chords ring out in the obscenely large, and largely empty, room. It was a beautiful, rich sounding grand, hard to resist; these days he was only playing out of tune, often ancient uprights, like the one he had acquired for $150, a gift from Katie and Harv Koontz. (The following year, 1966, he abandoned it in his Descanso Street apartment after sawing off its corners to fit it up the stairs, smashing through an exterior wall and triggering a lawsuit in the process; Pauline contributed to its replacement.) In the evenings after work, he’d been writing as much as he could, and he was more satisfied with some of his recent songs than he was with his drawings, which seemed to be spiralling solipsistically into themselves, never expanding into something external or autonomous.

In 1964, after a knock down, drag out fight with Jo Harvey, “a free for all screaming pan thrower” — a fairly regular occurrence as he spent more and more time in the studio and away from Jo Harvey, even sneaking out of bed at night to work — he’d written “Red Bird”, which he considered his first song worth keeping, the first one “that felt like a real song”, and perhaps still his most personally significant. Even though it sounded to him suspiciously similar to Johnny Cash’s 1958 hit “Ballad Of A Teenage Queen”, or perhaps because of it, he recognised its fully fledged nature, and its primacy among all his other songs, almost immediately. “Probably because it’s strange,” he wrote of its cryptic lyrics about an allegorical red bird prisoner in New Orleans, “I felt great about the song and dumped yards of neurotic agony into it.” Jo Harvey lay in bed upstairs in their rental duplex on Benton Way in Rampart Village, where they lived for the majority of Terry’s college years, listening to him work it out, her rage settling into curiosity. “Red Bird” was the song that his friends always wanted to hear him play, the undisputed favourite among his peers. Sometimes he doubted if they knew the names of any of the others.

He liked “Freedom School” too, though he sensed correctly that its context of Chouinard politics might be too opaque to appeal broadly. Provoked by his fellow students’ incipient anti-Disney protests, as well as his struggles with his own work, it stands out for its topicality and apparent ambivalence about his education.

Sitting at the piano in Hollywood Hills that afternoon in the summer of 1965, he played neither of those songs, however. Instead, his fingers settled into the opening A major chord of a tune called “Big Time Hollywood Businessman”, appropriate, he thought wryly, given the location. He played for a few minutes, pushed back the piano bench, and saw Dean standing in the doorway grinning.

“I didn’t know you could play like that. Did you write it?”

After recovering his composure, Terry answered affirmatively and nervously. He hoped Dean hadn’t taken offence at the subject matter.

“How’d you like to be on television? I produce a program called Shindig!”

Shindig! was a new music variety show on ABC, shot in front of a live audience but heavily edited, that pandered, rather shamelessly, to a teenage demographic in thrall to rock and roll and soul. It was only in its first season, having premiered a year earlier, a last minute replacement for its predecessor, Hootenanny, which had been oriented toward folk revival fare that was now, at least according to ABC executives, hopelessly passé, having been decimated by the British Invasion. Terry and Jo Harvey had watched Shindig! occasionally, though at 22 years old, they were already older than the target audience.

“Well, yeah, I’d like that, I guess,” Terry squinted and grinned right back, unsure if this was a joke.

Dean invited him to dinner that weekend, where they could discuss the opportunity further, asking him please to bring his lovely wife. Dean’s previous familiarity with Jo Harvey was limited to an episode weeks earlier when, on her way to pick up Terry from work, she had stalled their Beetle on the steep, winding road up to the house, slipping backward off the shoulder and denting the car. Frustrated and embarrassed, she leapt out of the vehicle, and she and Terry hollered orders and abuse at each other at a distance, much to Dean and Will’s surprise and amusement.

Over the course of drinks and dinner, Jo Harvey managed, as she often did, to charm her hosts utterly, laying on her aw-shucks confidence, dazzling storytelling chops, and honeyed Lubbock accent as thick as the title of another recent Allen composition, “Smooth Butter Device”. Will, who had grown up in the South, was particularly beguiled, resulting in him and Dean protectively taking this young couple of naive West Texans under their collective Hollywood wings, employing Terry more, occasionally feeding them both, and offering nuggets of show-business and life advice.

At dinner Dean instructed Terry to attend an audition a few days later, writing down the address for him. Terry showed up at “some place out on Western Avenue, some little rathole”, where he rushed through Lead Belly’s “Lining Track” until the casting director told him to stop playing—he’d made the cut. They gave him a date and told him to await future instructions. As producer, the final decision was technically not Dean’s, but since Terry was completely unknown compared to the other talent that Shindig! was regularly attracting — Sam Cooke, The Everly Brothers, The Beatles, The Beach Boys, The Rolling Stones, The Hollies, and Allen’s hero Bo Diddley — it seems likely that Dean had put in a good word to grease the wheels. If there had been any remaining doubts about Terry’s viability as a performer, Dean had forgotten them in his and Will’s delight at Jo Harvey’s dinner performance.

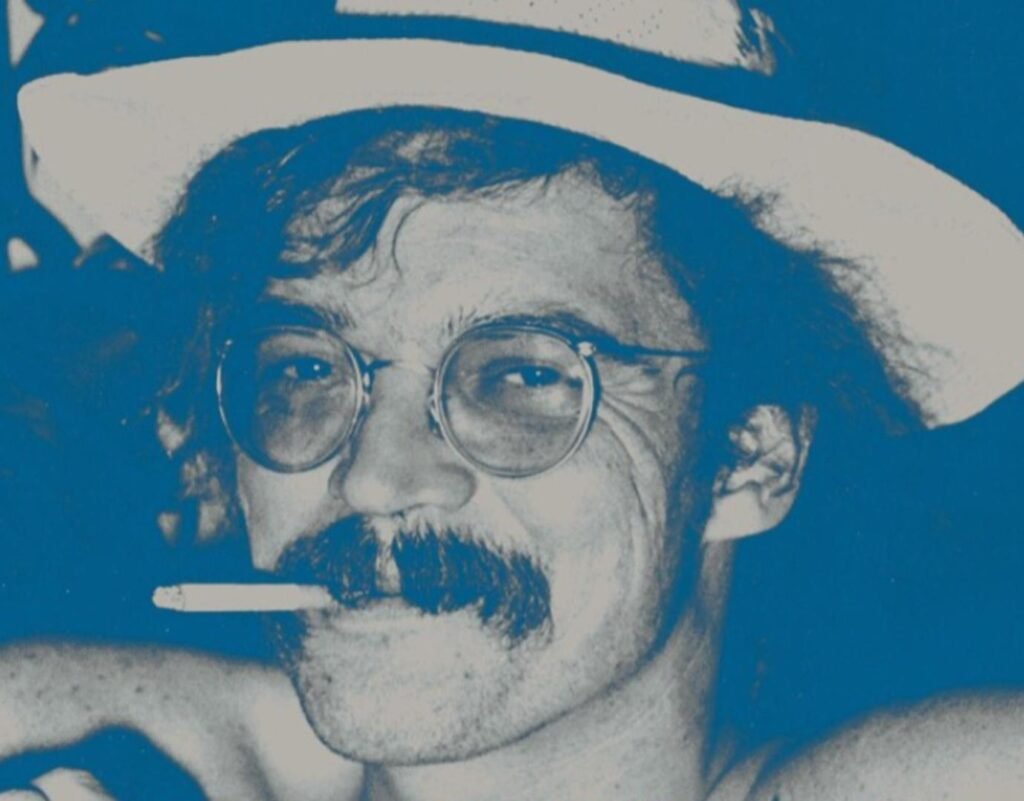

Weeks passed without Terry thinking much about his impending television debut, until the date of filming approached. Filled with dread, he drove to the studio, where he was cursorily introduced to the director, Richard Dunlap, and the host, Jimmy O’Neil, neither of whom appeared impressed with his appearance. He was wearing the horrible pants, which he regretted as soon as he walked on set, with suede Chelsea boots and a dark waistcoat over a light collared shirt. His hair, unruly and densely curly, though still relatively short, resembled, in his words, “a Brillo pad”.

His heart fell when he discovered that he was the sole novice artist booked for the episode, which would air a few weeks later, on 4 August 1965. His fellow performers included The Righteous Brothers, who would debut “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling”, and the Great Scots, a gimmicky, be-kilted beat band from Nova Scotia whom Terry regarded dismissively as “some Beatles rip off group”. He was more excited about his female co-stars: the infectious New Orleans vocal trio The Dixie Cups, of “Chapel Of Love” fame, who had recently released their hit version of the Mardi Gras Indian classic “Iko Iko” (Terry was a sucker for New Orleans music), and the languid, radiantly sexy London singer Marianne Faithfull, a protégée of The Stones and their manager Andrew Loog Oldham.

Unsure what to do with himself or where to stand, Terry walked over to the most approachable looking cluster of musicians he saw, who were gathered around the back line, laughing. Led by Billy Preston, the multi-talented keyboardist, singer, and songwriter who had backed Little Richard and Sam Cooke and would, within a few years, work with The Stones and join the inner circle of The Beatles at the brink of their breakup, the Shindig! house band, ridiculously dubbed The Shindogs, also had an integral Lubbock connection, which was, as Allen puts it, “really fortuitous”, considering his agitated state of mind. Two Crickets were, respectively, a regular featured player and a steady Shindog: guitarist Jerry Naylor, who fronted The Crickets for four years after David Box’s death, and pianist and honorary Cricket Glenn D Hardin. Naylor immediately shook Terry’s hand and set him at ease. The two commiserated about David’s tragic death the year before. Jerry introduced Terry to the other Shindogs, an astonishing lineup of brilliant young musicians on the cusp of fame, including, at various times, Glen Campbell, Leon Russell, Delaney Bramlett (later of Delaney & Bonnie), and guitarist James Burton (the only one Allen clearly recalled meeting).

When it was Terry’s turn to play, a stage manager told him he would have two minutes to play his two songs and that, due to set changes, unlike the other performers, he would not be joined by the programme’s famously kinetic, often silhouetted backup dancers. He brusquely pointed out the cameras and the position of the piano. Terry nodded, understanding nothing, sweating through his shirt. He stepped cautiously into the centre of the vast stage set, empty except for the absurd piano they’d found for him. An enormous upright with tawdry baroque detailing and filigrees, lit with a spotlight, it looked like it was borrowed from the saloon set of a Western TV series, which it may well have been, in an attempt to provide some visual interest and regional context for this gangly Texan’s solo act.

Terry’s brief clip, black and white like all the Shindig! footage, represents the earliest surviving example of his music as recorded to time based media, either visual or audio. It begins with the camera on a crane above the shoulders of the silhouetted Shindogs. As it’s lowered, the camera tracks across the soundstage toward Terry, already hunched over the meretricious upright, pounding away at “Red Bird”, at a tempo even brisker than usual. As the camera approaches from behind, you notice how his vest is awkwardly scrunched halfway up his back. You can hear and see his right Chelsea boot stomping away heavily on the riser to keep time, heel and toe swivelling wildly, the first manifestation of a percussive feature that has plagued many sound engineers and broken many piano pedals over the decades and is still evident in all his music today. As the camera turns to shoot him in profile and then close up, Allen himself turns toward it in three quarters profile, alternately smiling and snarling through the lyrics, head waddling and nodding maniacally. He’s wearing a harmonica rack, which is suddenly revealed to be jury-rigged with a kazoo, an instrument never again featured in his music, which he toots for an entirety of four measures — four seconds — in a transitional gesture before accelerating the same chord progression and rhythm just slightly and tearing into “Freedom School”.

The unnatural screams of young girls erupt periodically, seemingly randomly, encouraged by mechanical teleprompters in the audience, and then suddenly subside. They sound like screams of terror, more apposite to horror movie than matinee idol. More kazoo follows between verses, and his voice drops into an occasional growl as he bares his teeth. By the end of this obviously rushed, slightly unhinged performance, Terry, his eyes squinting and bugging behind his heavy black-framed glasses, resembles some demonically possessed avatar of Buddy Holly. Suddenly he stops playing and rotates on his piano stool to the audience, looking abashed and relieved, and very much himself, a shyly smiling 22 years old young man, slouching with his hands shyly between his knees, drained of all that freneticism, wondering what on earth he is doing there. A title reads, as if by way of apologetic explanation, “…THAT WAS TERRY ALLEN”. The whole thing is over in one minute and 44 seconds, safely under the allotted time.

Out in the audience, Jo Harvey was thrilled, beaming with pride, perhaps the only person there who did not need to be prompted to scream in delight. Sitting right behind her was a smartly dressed British man in his early thirties, obviously not a local or a teenage audience plant. He raved about the performance, exclaiming repeatedly, “This guy’s great!” When, following her husband’s set, Jo Harvey turned to introduce herself, he cordially introduced himself in turn as Brian. Dean quickly informed her that “Brian” was in fact Brian Epstein, the manager of The Beatles, who was presumably there because of his friendship with Faithfull. He asked Jo Harvey for their phone number, shook her hand again, and told her that he’d be in touch. Elated, Jo Harvey told Terry about the exchange as soon as they had a private moment together. “I told Terry, ‘We’re going to be so rich!’” They’d only been in California two years, Terry was still in school, and here was their big break. After the shoot wrapped, they drove to Dean and Will’s to celebrate and asked to borrow a few hundred dollars — Terry claimed $200, Jo Harvey $500 — which they assumed they’d easily be able to pay back as soon as Epstein called and signed Terry. He’d be on TV every week, they were certain. They drove down to Laguna Beach for the weekend and blew the entire loan. Brian Epstein didn’t call on Monday. He never would. “Of course, nothing happened,” Terry said. He had to pick up extra hours to pay his patrons back. Exactly one week after Terry’s episode was broadcast into living rooms across the nation, a too common incident of police brutality perpetrated against a young Black man named Marquette Frye ignited five days of riots — sometimes known today as the Watts Uprising — in and around the Watts neighbourhood of South LA, throwing the city into chaos and racist hysteria. The tumultuous era we regard in cultural historical terms as ‘the Sixties’ had officially arrived in Los Angeles.

The rush of Shindig! and the disappointment of its anticlimactic aftermath impelled him to concentrate more seriously on his songwriting. He secretly wondered if Epstein would have called had he chosen different songs to play, earworms impossible to forget over the course of a weekend. Of course, he didn’t have many others from which to choose, at least not any that felt sufficiently current or vital for national television. So he got to work, grinding down pencils to their nubs and emptying pens on pages of lyrics. Through 1966 and 1967, songs piled up, in various stages of completion and degrees of satisfaction. He didn’t own a tape recorder yet, so they all still existed only in lyrical form in notebooks and songbooks, handwritten and typewritten, respectively. Most of these mid 1960s songs are built on two, or occasionally three, major chords, alternating riffs, mid-tempo to positively peppy, with additional changes at turnarounds and choruses. There are seldom bridges or multiple parts. The titles are often amusingly evocative, if sometimes outrageously florid, and the lyrics tend to be either incomprehensibly bizarre and disjointed or forgettably slight.

He still regularly performs many of the songs he began writing immediately following this period, some of which he has recorded more than once, but his pre-1968 songwriting output, much like his visual art output of the same era, is notable for its dead ends, entombed (unusually for Allen, who never learned to read music) in sheet music transcribed for an abortive publishing deal and unresolved recording sessions. Other than “Red Bird”, Terry would never revisit any song from this stack, allowing them to languish in the past.

Truckload Of Art: The Life And Work Of Terry Allen is published by Hachette Books.

Wire subscribers can read George Grella’s interview with Terry Allen from 2020 in The Wire 432 and Byron Coley’s review of Truckload Of Art: The Life And Work Of Terry Allen in The Wire 484 via the online library of back issues.