Early life and training

Orozco first became interested in art in 1890, when his family moved to Mexico City. Going to and from school each day, he paused in the open workshop of José Guadalupe Posada, Mexico’s first great printmaker, whose grotesque caricatures and illustrations appeared in sensational broadsides (single printed sheets intended for a largely illiterate public) devoted to reporting lurid crimes and political scandals. Orozco was captivated by Posada’s strong images and vivid style, and for the rest of his life he acknowledged the early influence of the master engraver.

Orozco began night classes in drawing at the Academy of San Carlos. Toward the end of the 1890s, his pursuit of art was interrupted when he obeyed his father’s wishes that he study to become an agronomist and, later, an architectural draftsman. When he was 17, however, he lost his left hand in a laboratory accident, and he abandoned his architectural studies. He reentered the Academy of San Carlos in 1905 with a renewed passion for painting, and he assiduously set about to become a competent painter.

Britannica Quiz

Ultimate Art Quiz

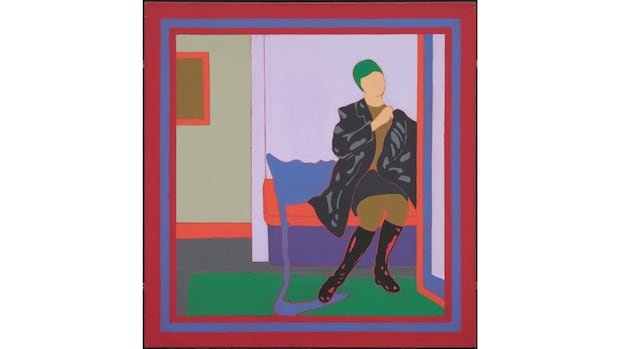

One of Orozco’s teachers at the Academy was a radical artist named Gerardo Murillo, who had assumed the Aztec name of Doctor Atl. He urged artists to reject the cultural domination of Europe and to cultivate Mexican traits in their work. Inspired by Doctor Atl, Orozco conscientiously began to explore Mexican themes and to draw more directly from scenes of daily life. He became a caricaturist for an opposition newspaper and haunted the barrios, or slums, of Mexico City, painting a series of watercolours dealing with the lives of prostitutes that was collectively titled House of Tears. When civil war broke out in Mexico in 1914, Orozco supported the forces of Gen. Venustiano Carranza by working as a satiric artist on the revolutionary paper La vanguardia (“The Vanguard”), which was edited by Atl.

Mature work and later years

In 1917 the negative reaction of critics and moralists to the exhibition of his House of Tears paintings compelled Orozco to leave Mexico for the United States, where he lived for several unhappy years in San Francisco and New York City. On his return to Mexico in 1920, he found that the new government of Pres. Álvaro Obregón was eager to sponsor his work, and, along with his colleagues Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and others, he was commissioned to paint murals (1923–27) on the walls of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City; these artists’ efforts initiated the Mexican muralist movement. Orozco was dissatisfied with his early murals there; he decided they were too derivative of European traditions, and he destroyed many of them. Those works dating from 1926, however, such as Cortés and Malinche (1926), show him coming into his own style, achieving a monumentality unprecedented in Mexican art.

In 1927 the government withdrew its patronage and protection from Orozco and his fellow muralists, and the subsequent attacks of critics and conservatives again convinced him to move to the United States. Humiliated in his own country, he consciously strove, after settling in New York City, to forge an international reputation that would force his countrymen to recognize his value as an artist. He gradually became known in American art circles and was commissioned in 1930 to paint a major mural in the refectory of Pomona College in Claremont, Calif. In choosing to do a mural of Prometheus, Orozco temporarily abandoned social criticism and historical subjects in favour of a more universal theme: the self-sacrificing Titan from ancient Greek mythology who brings man fire. Orozco also turned away from the relative stylistic repose of his earlier murals. Inspired by the tortured figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, he portrayed Prometheus as a monumental pseudo-Michelangelesque giant, straining his powerful muscles against the burden of his fate. By contrast, Orozco’s murals (1930–31) at the New School for Social Research in New York City, dealing with the themes of universal brotherhood and social revolution, suffer from a slavish use of “dynamic symmetry,” a theory fashionable in the 1920s that purported to represent the ancient Greek system of proportions.

In 1932 Orozco made a brief trip to Europe, where he viewed the art of England, France, Spain, and Italy. Although he was impressed with the paintings of Pablo Picasso, his even deeper admiration of the Byzantine mosaics of Rome and Ravenna is reflected in his great series of murals (1932–34) in the Baker Library at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. Orozco created two series of murals there that correlated to two main scenes, The Coming of Quetzalcoatl and The Return of Quetzalcoatl. This dichotomy contrasted the stages of human progression from a primeval, non-Christian paradise to a Christian, capitalist hell. Byzantine mosaics also clearly influenced the pictorial style of Modern Migration of the Spirit, but such scenes as Gods of the Modern World and the Quetzalcoatl murals achieve unique levels, respectively, of grotesqueness and of sweeping force.

With a mature body of work and a firmly established reputation, in 1934 Orozco returned triumphantly to Mexico, where he painted the mural Catharsis for the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City (1934). In this eschatological work he depicted a laughing prostitute lying among the debris of civilization’s last cataclysm. The pessimism that increasingly marked his work finally culminated in his Guadalajara murals (1936–39), which he painted in the lecture hall of the University of Guadalajara (1936), the Governor’s Palace (1937), and the chapel of the orphanage of Cabañas Hospice (1938–39), respectively. In these murals Orozco recapitulated the historical themes he had developed at Dartmouth and in Catharsis but with an intensity of anguish and despair he never again attempted. He portrayed history blindly careening toward Armageddon. The only hope for salvation in these works is the self-sacrificing creative man who Orozco depicted in Man of Fire, the circular painting in the hospice dome.

In Orozco’s subsequent murals—such as those in the Gabino Ortíz Library in Jiquilpan (1940) and in the Palace of Justice in Mexico City (1941), as well as National Allegory (1947–48) at the Normal School in Mexico City—he emphasized nationalist themes to the exclusion of the universal. Canvases such as Metaphysical Landscape (1948), however, hint at a growing mysticism, and its abstract style suggests that Orozco may have been on the brink of nonfigurative painting when he died.

Orozco became a national hero in his later years, honoured as the leader among those who raised Mexican art to a position of international eminence. He published his autobiography in 1945 (Eng. trans. 1962). In 1947 the president of Mexico awarded him the Federal Quinquennial Prize, which recognized him as the outstanding Mexican figure in the arts and sciences of the preceding five years.