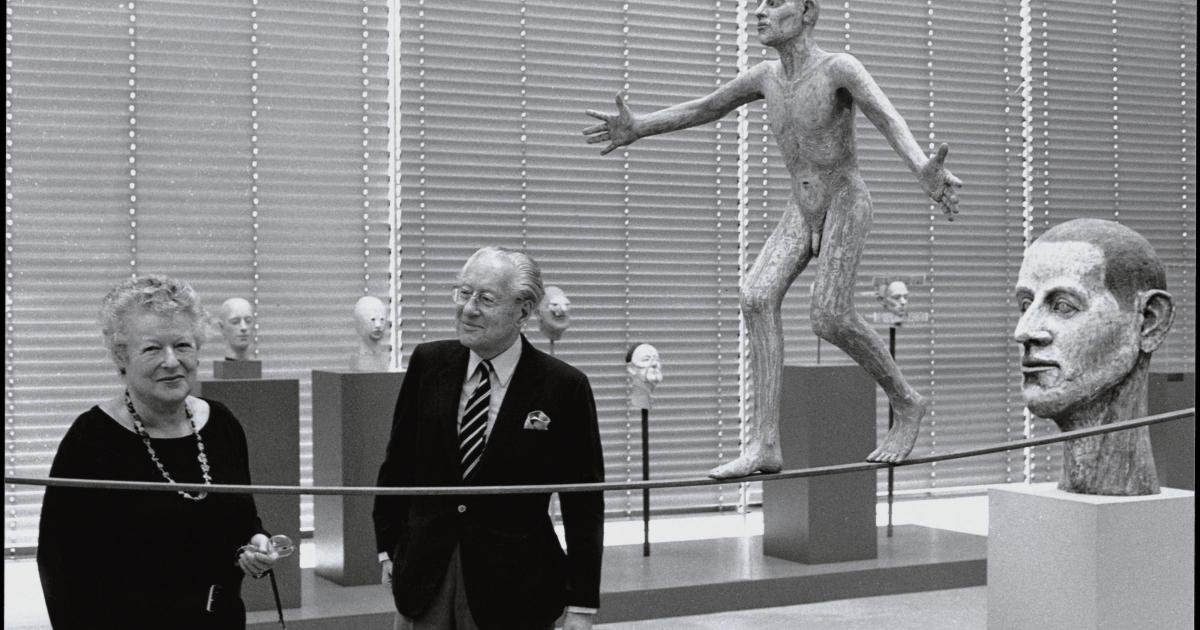

Mike Smith meets Michael at his home in Alvaston

A man is wandering alone through a dense wood when he comes to a fork in the path. He is faced with a difficult decision about the route that he should follow, for there is little to choose between the alternatives. Eventually, he decides to opt for the left-hand path and steps out purposively on his way, even though he finds it difficult to dispel lingering doubts about the wisdom of his decision. As he walks, he turns his head to glance back at the route that he might have taken.

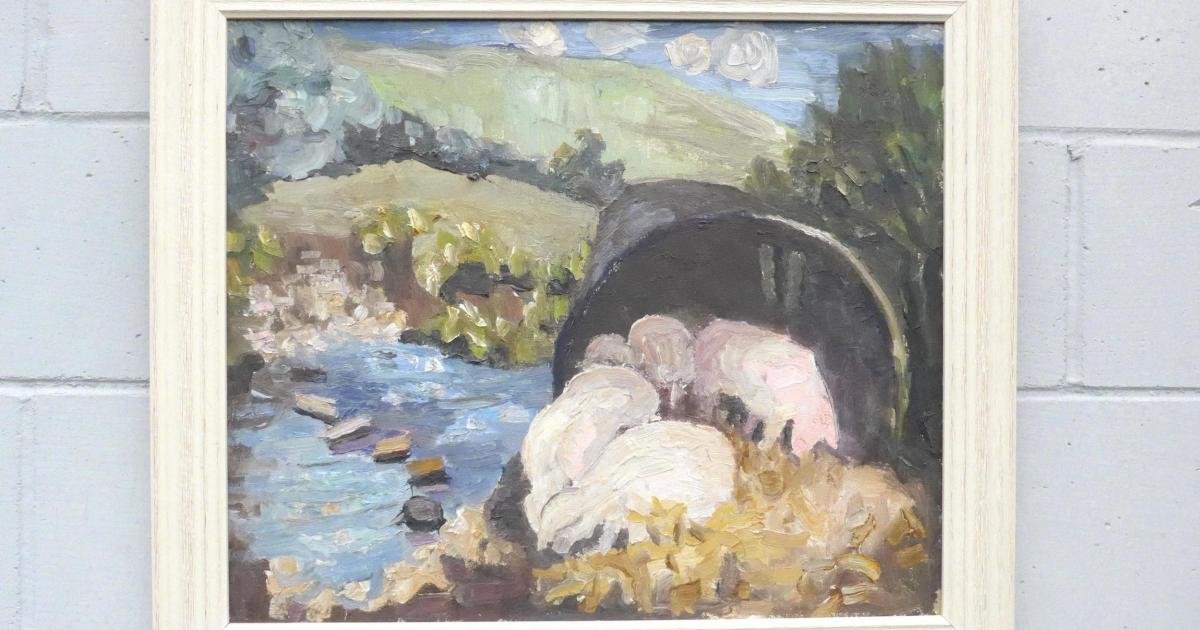

This story is told in a painting by Derbyshire artist Michael Cook, who clearly took his inspiration from Robert Frost’s well-known poem ‘The Road Not Taken’. Michael’s picture speaks clearly to everyone, because it is a graphic illustration of the many difficult choices that face all of us as we take our journey through life.

As I would discover when I spoke with the artist at his home in Alvaston, near Derby, Michael has had to make some difficult choices of his own at various points in his life, but his decision to pursue a career that would make use of his artistic talents was not one of them. In fact, that choice was made when he was still a pupil at his junior school in Melbourne.

Recalling the reason for this early decision, Michael said: ‘A teacher called David Bell recognised my artistic ability and provided me with lots of encouragement. He even gave me a wall in the classroom where I could paint and draw. When other members of the class were listening to a story at the end of the school day, I would be allowed to create pictures on what became known as ‘Michael’s Wall’. I can remember producing illustrations from ‘The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe’ whilst the class was listening to the story being read by Mr Bell.’

When Michael moved at the age of eleven to a secondary school at Chellaston, he discovered the art books in the school library, where he saw reproductions of paintings by the likes of Leonardo and Picasso. He also recalls being particularly impressed, even at that age, by the work of Marc, Munch and Feininger, all of whom have clearly left their mark on his own style. With regard to subject matter, Michael says, ‘Most of my pictures recall the days that I spent wandering alone through the Derbyshire countryside, where I discovered both the beauty and the pain of Nature.’

Although Michael was determined to follow a career in art, he was pragmatic enough to select a further education course in graphic design, thinking that it would prepare him for a steady job, rather than leaving him to starve in a garret as a struggling artist. However, he was delighted to find that his course did include life-drawing classes, which became his only real training in fine art.

Looking back on his 20-year career as a graphic artist in the publishing industry, Michael said, ‘I have no regrets, because my job allowed me to make some of my most enduring friendships, but I did become increasingly frustrated as time passed. Hoping to find work that would benefit people, I even took on some extra employment as a mental health worker. I also began to reduce my working week as a graphic designer so that I could devote some days to painting.’

The decision to become a full-time artist was almost made for Michael by his employers when they started issuing redundancy notices to many of their staff. But the possibility of living entirely by his art was brought home to Michael by the success of his first one-man show at the Ingleby Gallery in 2000, when he sold every one of the 23 paintings in his exhibition. One of the people who bought his work was David Bell, the mentor from his primary school days.

Although Michael now lives as a full-time artist, he admits that he is fortunate in having the loyal support of his partner, Paul Dimmock, a gardener at Elvaston Castle, who is happy to become the main bread-winner during occasional dips in cash-flow. Pleasantly surprised that his pictures have sold so well, Michael says, ‘in many ways, my art does not fit into what is fashionable, but the impression that I get from many of the people who like my work is that they have been a bit starved of meaning and beauty in much of the art that is currently on the market.’

Michael produces paintings that are both beautiful and meaningful. He begins each new painting with a few bold marks, often starting with random squiggles, without having any idea about his final image. As he builds up his picture in acrylic paint, he combines all the elements in the composition into an integrated whole, whether they are human figures, flora or fauna, often making use of wave-like forms. When he is happy with the result, he works over the entire painting with oil pastels.

Even after all these years, Michael’s paintings are essentially a distillation of memories from those childhood rambles through rural Derbyshire. Some pictures feature lone wandering figures that appear to be dreaming or searching as they undertake long journeys. Other paintings depict animals, always drawn from memory, rather than from life, and usually shown in the act of leaping, prowling or hiding.

Michael said, ‘I deliberately employ Nature as a metaphor for emotions and I also use human figures to express mystery and spiritual longing, but I have absolutely no intention of hitting people over the head with meaning. I want to leave room for them to make their own response to my paintings.’

Although many of the subjects in the paintings have emerged from the artist’s own imagination and memory, he is equally adept at responding to commissions where he has been given a theme. A painting commissioned for the baptistery at the Church of St Augustine at Bolton is an interpretation of ‘Moses Striking the Rock at Horeb’ and a picture called ‘Every Dream I Dream is You Somehow’ is a poignant and touching response to a request from Johan Hearn for a tribute to the memory of her late husband, David. It comprises images of things that were important to him in life.

Michael was one of just ten artists nationwide who were asked to submit a design for a tapestry for the high altar at Winchester Cathedral. Eventually, the competition was won by the celebrated artist Maggi Hambling, but Michael is obviously delighted to have been asked!

Collaborations have been a feature of Michael’s recent work. For example, ‘The Garden in Darkness’, a series of 13 paintings created for the chapter house at Southwell Cathedral, was accompanied by written responses from Rosalind O’Melia, music from violinist Joy Gravestock and puppetry from Jane Darrell. At this year’s Melbourne Festival, he will be exhibiting ‘Thank You for the Rain’, in collaboration with Rosalind O’Melia, artist John Rattigan and lettering-artist Elizabeth Forrest. And for the Wirksworth Festival, he will be asking Rosalind to provide written responses to ‘The Hours’, a series of five paintings based on the monastic day.

Michael is delighted that his work is on show in churches. Although he was single-minded about following his career path, he took more time to accept the religious beliefs that now inspire many of his pictures, which nevertheless remain meaningful for people without faith. In effect, his painting of ‘The Road Not Taken’ can be read as a metaphor for his spiritual life. After by-passing a path that would have led him to religion much earlier in life, he is now following ‘The Road Not Taken’.

Michael Cook’s work can be viewed on www.hallowed-art.co.uk.