“At times, I felt like it was the best way to be. The race conflict in the US is often framed between black and white, and if you’re neither you get to opt out of the conversation. You’re not burdened by it, at least when you’re young,” he says.

Although my paintings are not about Hong Kong objectively, they’re almost an obscure, refracted vision of Hong Kong

Years after moving to New York, Shew came across the portraiture of Alice Neel and Martin Wong, whose subjects included Asian-Americans. Deeply inspired, he saw “a thread I wanted to follow and pull on”. And so he began to paint portraits of Asians.

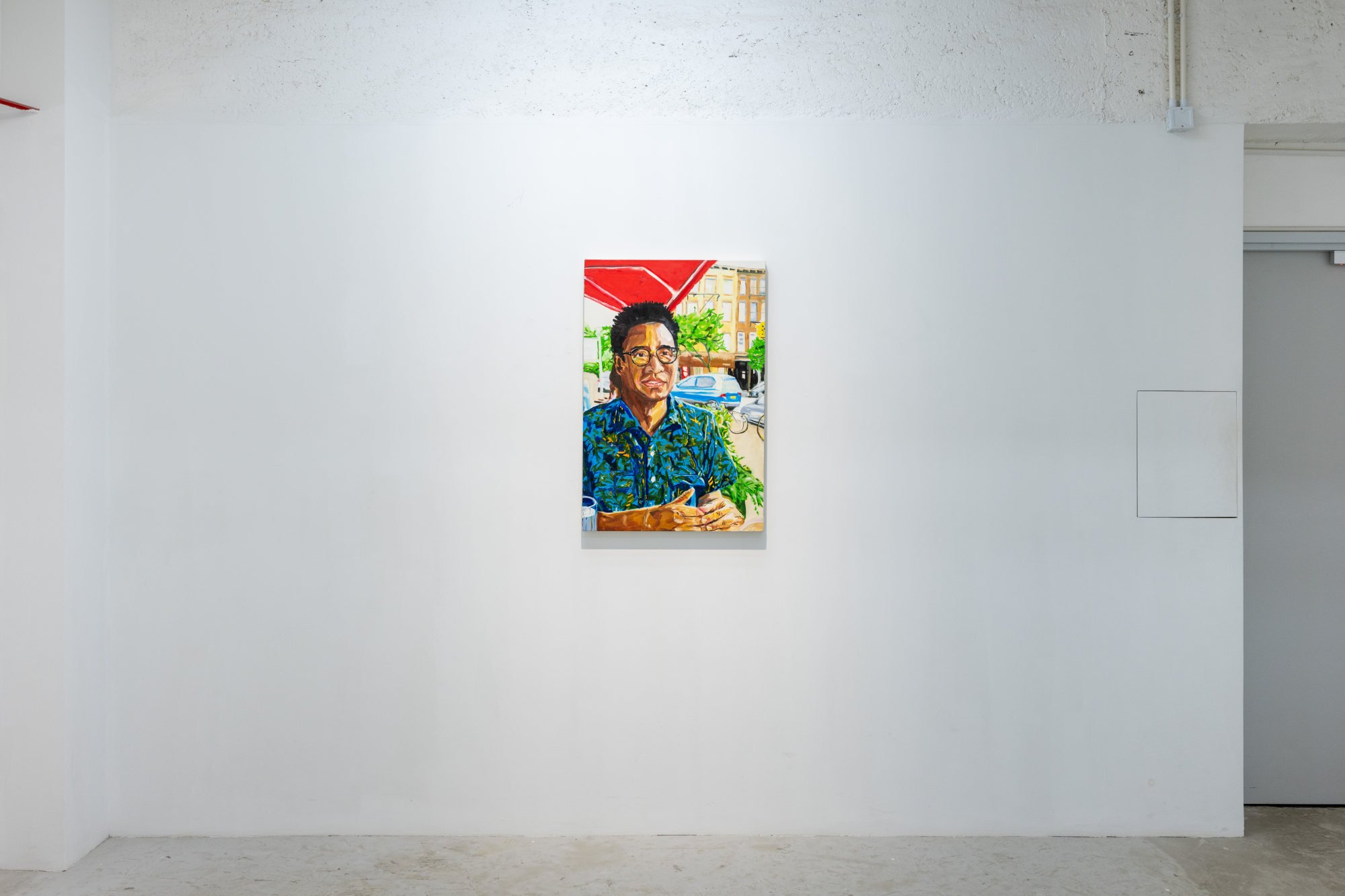

A highlight of “Meanwhile”, Shew’s second solo exhibition in Hong Kong, is Hua Hsu II (2023).

Serving as an “update” to the artist’s first portrait of Pulitzer Prize-winning Asian-American writer Hua Hsu, the painting depicts Hsu in a Hawaiian shirt, blending in with the plants behind him as he sits casually, engaged in friendly conversation against the backdrop of a New York cityscape.

Similar second portraits in the show include Charlie Mai II (2023), Brandon Blackwood II (2023), Simon II (2023) and Chantal II (2023), which all serve to show Shew’s artistic development as well as the way their subjects have changed as they age.

“Initially, I thought I was painting people who saw each other as in a community. I’m gradually realising that some of the people I paint don’t necessarily think of themselves as Asian-American. They are just Asians who live in America,” Shew says.

He says the Asian-American identity is a political one, in that “you want the US to change on your behalf”, whereas some people do not share this desire because they hold green cards or are students who do not attach the suffix “American” to whatever they call themselves.

“They somewhat change the political landscape of the US simply by existing there. The focusing lens for my painting is Asians in America,” Shew says.

He tells the Post that his mother, who left Hong Kong before its return to Chinese sovereignty and became a US citizen, sometimes says she is “emotionally a stateless person”.

“She votes, but doesn’t feel very American; yet [with] the state of Hong Kong since 1997 [it] doesn’t feel like her birthplace, either.”

He adds: “I’m sure the people in my life who feel that [way] have had an almost subconscious influence on me. Although my paintings are not about Hong Kong objectively, they’re almost an obscure, refracted vision of Hong Kong – another way in which people live in a transitory place.”

Huang’s work also explores feelings of displacement and being unsettled, but from another perspective.

Born and raised in Shenzhen, southern China, Huang does not fully identify as American. She and her family moved to New Jersey when she was 18, too late for her to reshape her understanding of herself, she feels.

“Even though I’ve lived in the States for nine years now, I consider myself more Chinese than American,” she says, “because I still carry a huge part of my background with me.” In her first few years living in the US, Huang often travelled to Shenzhen for extended holidays.

She always thought that she would move back to China after graduation. It was the Covid-19 pandemic that altered her idea of where home was.

“Those two years of the pandemic, a lot of unexpected, miserable events happened in China, in Hong Kong and in the States, which made me reflect and realise I couldn’t consider China as a place to return to any more,” she says.

Huang adds that often when walking in New York, where she went to university and now lives, she feels like she is abroad in a strange place. However, for the past couple of years, she has been attempting to change her mindset, to “push myself to really engage with the city”.

“Back in my undergrad years, I would never get furniture that cost over US$200, because I would have to get rid of or resell it one day. I just knew that I wouldn’t keep it.”

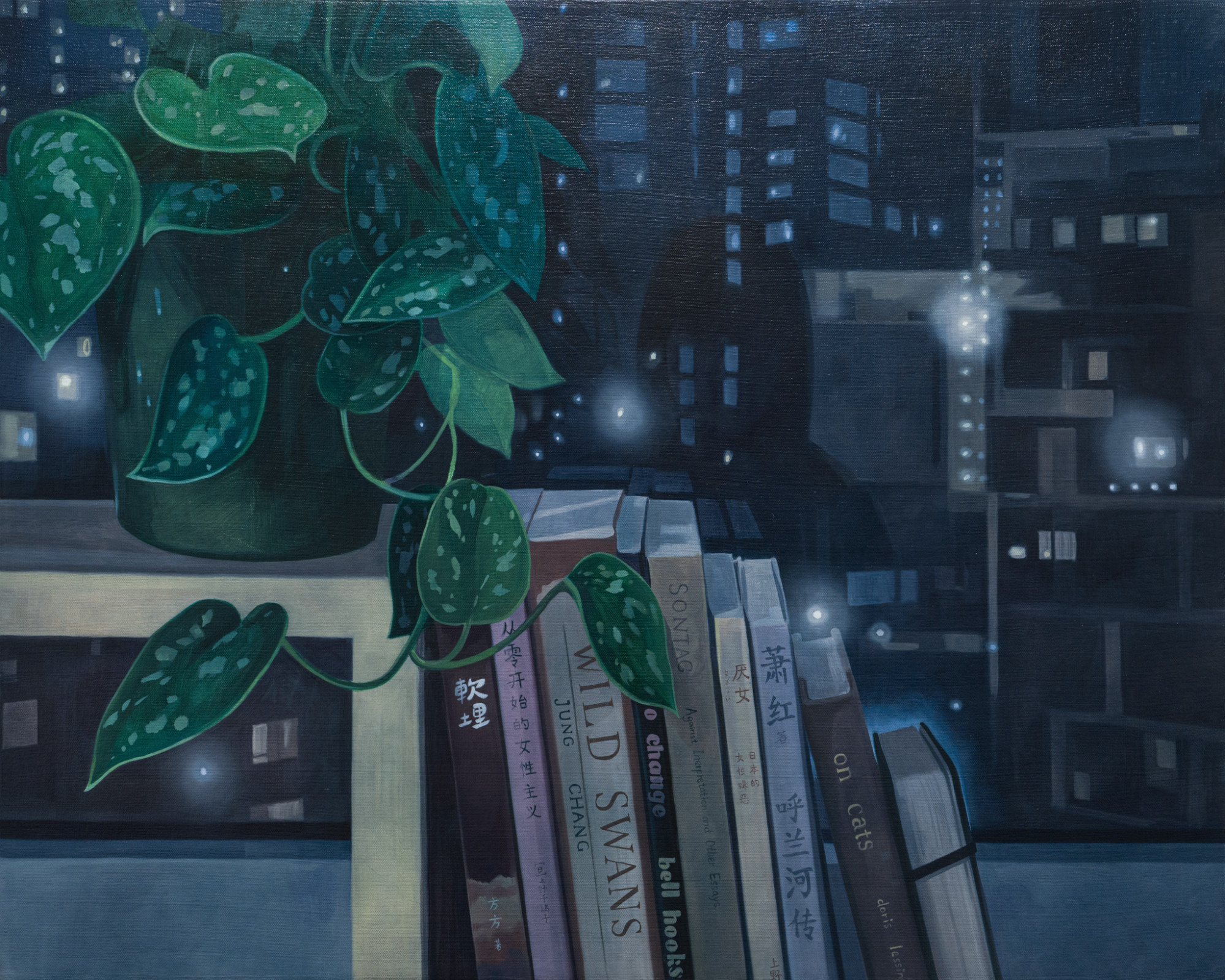

This nomadic lifestyle changed last year, when Huang finally got some plants for her New York apartment. Seeing her indoor plants grow day by day, she says, is very reassuring. “It’s like a mirror to see things grow inside of you.”

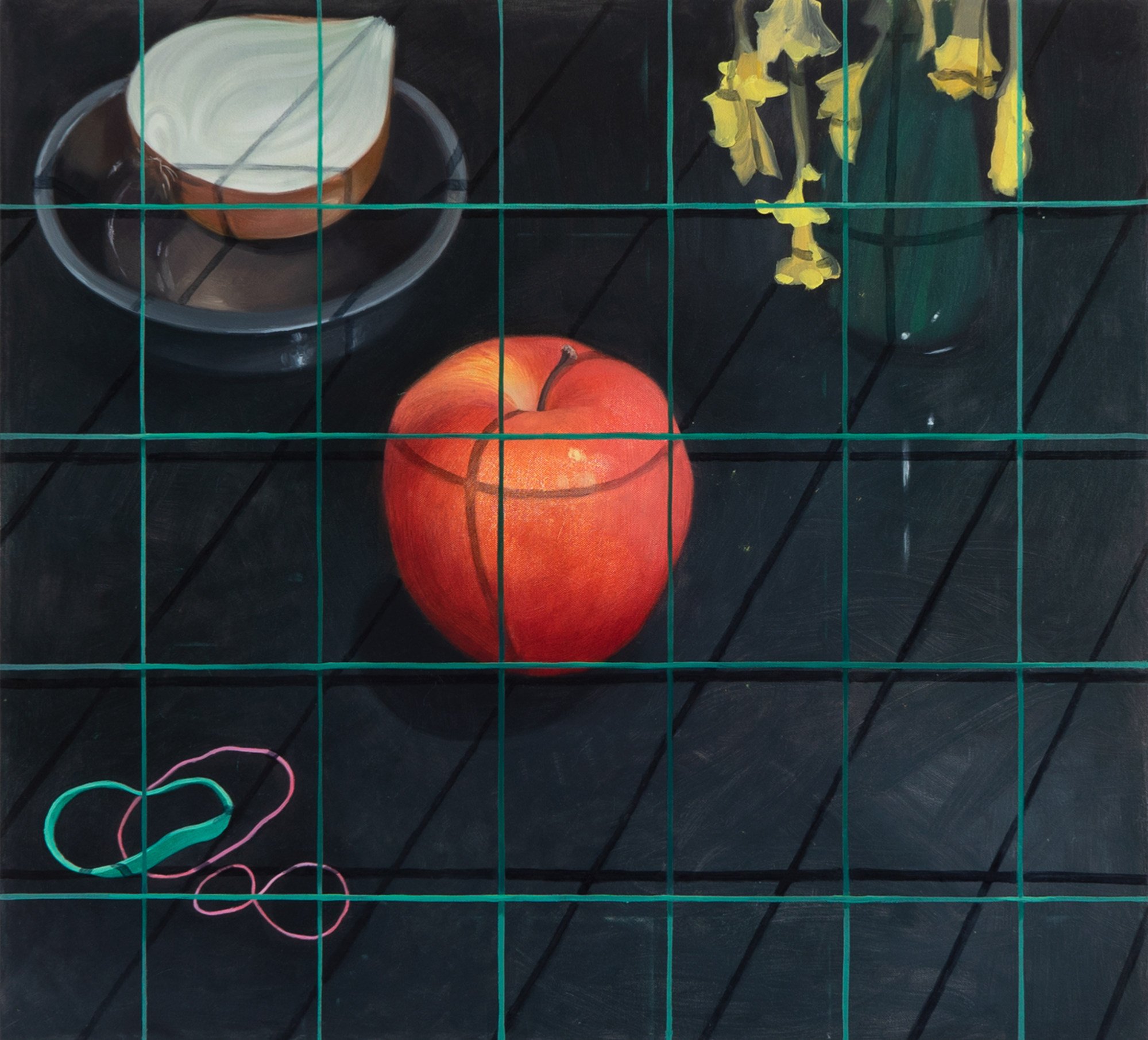

The centrepiece of her first solo exhibition in Hong Kong, “Choice of Oblivion and Remembrance”, Mother Tongue (2023) is a diptych of two bouquets of lilies, one in Huang’s home in New York and the other in her Shenzhen home.

In portraying the subtle differences in these seemingly similar scenes, she tells a personal story. The bouquet in New York travelled with Huang from China – a nod to the artist’s life.

She finds this diptych “very metaphorical”, since she feels she carried “a part of myself from my birthplace to my current life in New York”.

“What I’ve been constantly doing in my work is to register myself in the world and set up anchor points, whether it’s my living room, my bookshelves, my plants or a flower bouquet gifted by a friend. These are the moments that are visceral to me,” Huang says.

“I’m very sensitive and aware of how I feel. By keeping my work very close to my personal life, I have something to grasp, especially when I feel unsettled in between those two worlds which are polar opposites.”

Homer Shew: “Meanwhile”. Kiang Malingue, 12/F, Blue Box Factory Building, 25 Hing Wo Street, Aberdeen. Until December 2.

Huang Baoying: “Choice of Oblivion and Remembrance”. Mou Projects, 202, The Factory, 1 Yip Fat Street, Wong Chuk Hang. Until November 25.