Katherine Hubbard never intended to make work about her family. Known for her conceptual, often cameraless photographic practice and durational performances, she kept the personal at a remove. But when her mother was diagnosed with LATE, a brain condition mimicking the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, and caregiving became part of daily life, the boundary between art and necessity began to dissolve.

The Great Room – an elegiac, formally precise body of work made over several years in the decaying Philadelphia mansion her mother refused to leave – is less a documentary of illness than a meditation on time, architecture, and the quiet choreography of care.

‘The project started out of necessity,’ Hubbard explains. ‘When my mum started to get sick there wasn’t time to keep making work and care for her unless the two became one.’ The logistical constraints were intense: Hubbard was shuttling between her home in New York, Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, where she runs the MFA programme, and her family’s house in Germantown, Philadelphia. Her mother’s cognitive decline was evident long before any formal diagnosis, but the healthcare system’s slow pace – exacerbated by the onset of COVID – and the financial costs of outsourcing help, meant caregiving fell entirely on Hubbard and, eventually, her brother.

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

Set in the cavernous, crumbling home her mother inhabited for decades – a space bursting with architectural salvage and decades of unanswered correspondence – The Great Room is a quiet, immersive work that resists easy categorisation: part documentary, part performance, part sculpture. Born out of a long gestation period, in part owing to Hubbard’s preference for large-format film, the project took shape over the course of several years.

‘I basically brought all of my camera equipment, set everything up and just left it there,” says Hubbard. Living with the camera, ‘as a third wheel that cohabited with us,’ meant that it became just another piece of furniture in the house. ‘We never looked at any of the photographs,’ she says, ‘I just focussed on what it felt like to be with my mum in this place – if I cared about how things looked it would all dissolve.’

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

The images are staged but not theatrical, composed but never for the camera. Hubbard’s approach to performance is shaped by intimacy and the demands of illness. ‘Sometimes I could build life around the image. Sometimes the image had to fit into life.’ The house might be in chaos – spoiled food, exploded eggs on the ceiling, tenant complaints, a mountain of unopened mail – but within that, moments of stillness emerged. ‘Once we entered that space together, we had fun,’ she recalls. ‘We could do things that we couldn’t do while we were just getting through the day.’

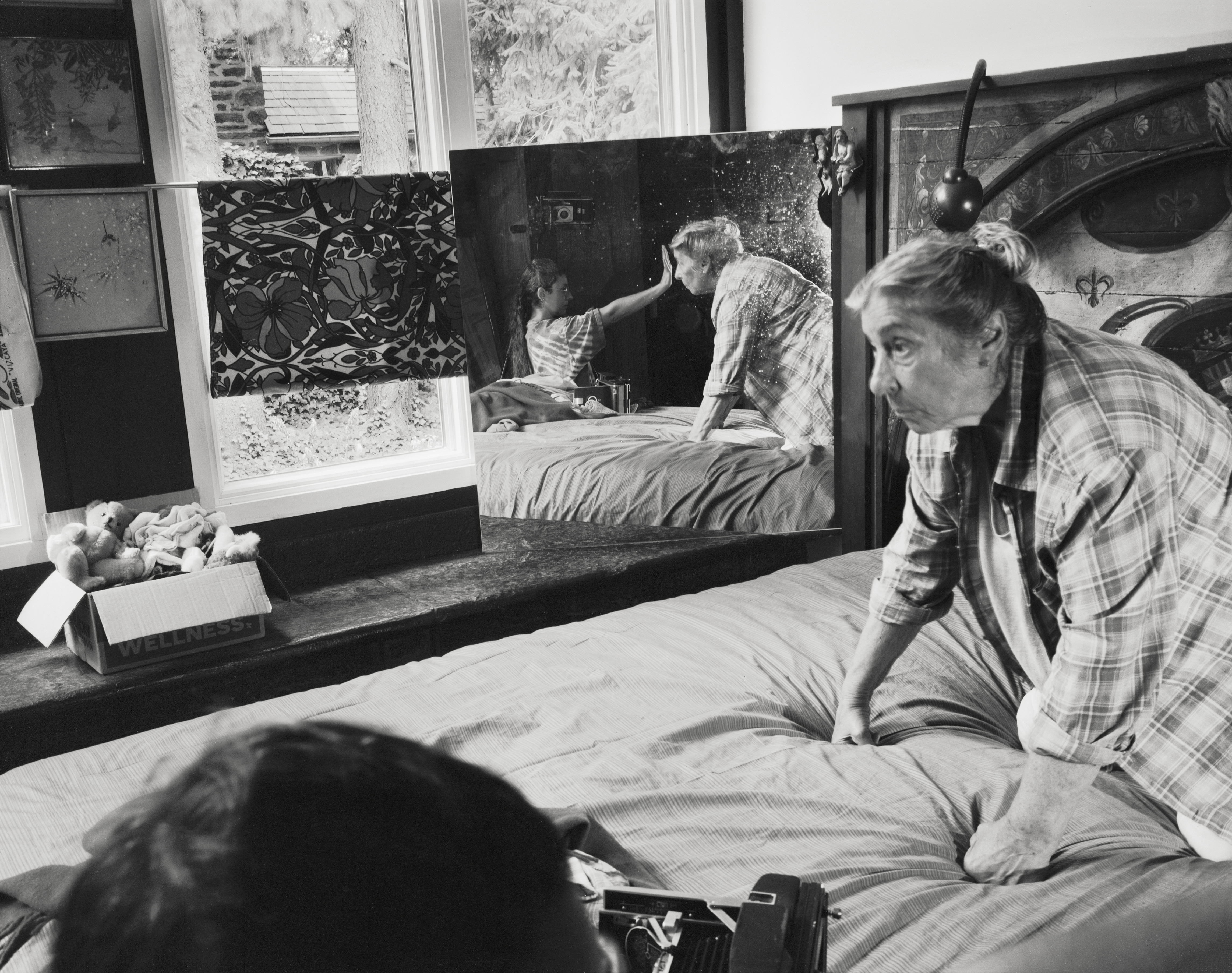

In the images, Hubbard is often present – her body, her reflection, her limbs – a subtle refusal of the photographer’s traditional invisibility. ‘I really wanted to be present in the images, but I also wanted to create somewhat of a fiction of my mum as the photographer, because I was really interested in the ways I could give her authority in the images – so she held the shutter, she triggered the image.’

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

There’s a radical softness at work here. In one photograph, the two bathe together, their limbs intersecting, barely distinguishable. “Bathing was somewhere I could really show the depths of our comfort with each other without asking her to simply stand naked and reveal herself,’ explains Hubbard. ‘By including my own body in the frame, I could protect that space.’

Antique mirrors, part of the extensive salvaged flotsam that her mother accumulated over a lifetime, allowed Hubbard to insert herself into the images while also serving as a threshold, between past and present, between seeing and being seen. ‘We very intentionally didn’t clean them,’ explains Hubbard. ‘So they’re not reflective, pristine surfaces, they dissolve the body and morph it. But when you move them, your hands take the dirt off, so they became these living props.’

As the house emptied in preparation for its sale, these gleaming, anachronistic mirrors served as sculptural anchors in the empty rooms, creating portals, echoes, layered lines of sight. ‘I didn’t want emptiness to symbolise death,’ she says. ‘I wanted to create a space of transition, of continuation.’ With The Great Room, Hubbard achieves something rare: a photographic work that resists spectacle and sentimentality in favour of something deeper – cohabitation, care, and the hard-earned aesthetics of interdependence.

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)

(Image credit: Katherine Hubbard, ‘The Great Room’)