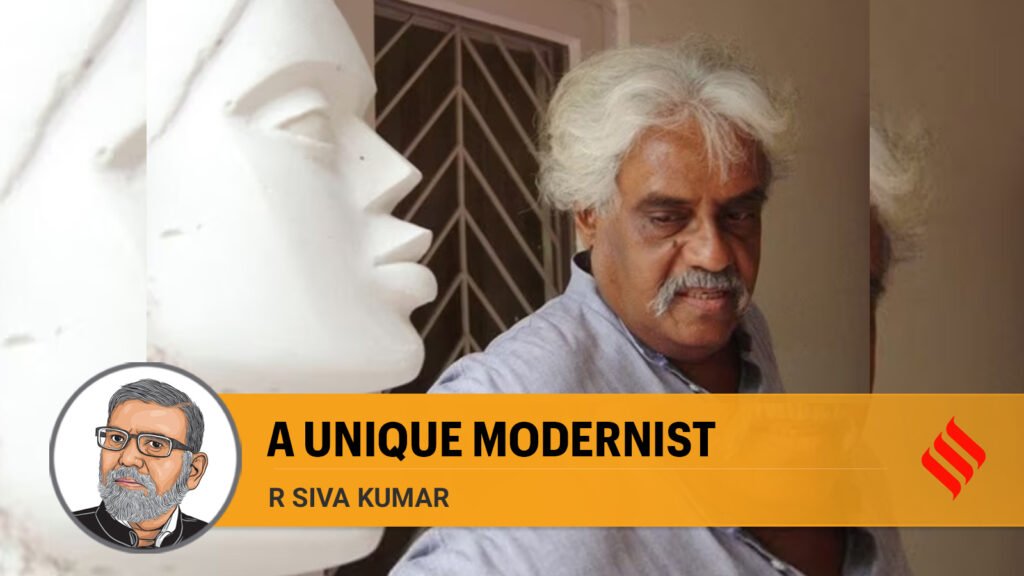

A Ramachandran, who passed away at 89 in Delhi on February 10, was an artist of great individuality and intellectual independence. As an artist, the range of his skills matched the diversity of his interests, and together, they made him a versatile and unique presence on the Indian art scene.

Born in Kerala in 1935, he began to paint and learn music simultaneously as a child and became an accredited Carnatic singer by the time he was 20 while continuing to paint on the side. Alongside, he also completed an MA in Malayalam literature and became close to the Progressive writers of the 1940s who had heralded a literary and social change in Kerala, and to contemporaries like G Aravindan and C N Sreekantan Nair who, like Ramachandran, would make a big splash in their fields. But a chance encounter with a reproduction of Ramkinkar Baij’s monumental sculpture the Santal Family — which in his view embodied values similar to that of the Progressive writers — changed the course of his life.

In 1957, giving up his fledgling music career, he shifted to Santiniketan to study art under Baij. Here, he discovered that Baij himself was part of a larger vision of art that had grown under the educational programme for social and cultural change envisioned by Rabindranath Tagore and that Nandalal Bose and Benode Behari Mukherjee, too, were part of it. Frequent visits to what was then Calcutta exposed him to the tragic aftermath of Partition and the human suffering it caused. An ardent reader of Fyodor Dostoyevsky, it shook him deeply, and he wanted to do in painting what the Russian modernist did in writing.

In 1964, he moved to Delhi, and as a struggling artist living on the edges of the capital alongside subaltern urban dwellers, he recognised their predicament was not significantly different from that of the victims of Partition he encountered in Calcutta. This prompted him to eschew the Western formalist modernism courted by his contemporaries and look towards alternative modernisms, like that of the Mexican muralists, to create hard-hitting images of human suffering, abjection, and angst. While this was largely an exception in art, it had parallels in literature and cinema. Similarly, even as he had his eyes fixed on contemporary social realities, he drew upon myths and ancient literature to forge metaphors to capture them.

In 1984, after berating human insensitivity towards fellow humans for 20 long years, faced with the violence unleashed against fellow citizens in his own city, he felt that his efforts as an artist had been futile. In a world afflicted by hatred and violence, he decided to use his art to instil beauty, an element that modernist artists, including himself had negated. He found his models in the Bhil villages and landscapes around Udaipur. He was led to them by his study of the miniature paintings of Udaipur in relation to its setting. It led him to realise that the conventions of miniature painting were not arbitrary but based on local realities. They were as logical, inventive, and imaginative as any other tradition and can be repurposed for contemporary use.

Ramachandran approached the Bhil peasant tribals with the humility of an anthropologist, not as a condescending, all-knowing moderniser. Where modernists saw underdevelopment, he saw a lost way of life. The large village lotus ponds, which progress-mongers saw as potential real estate, taught him the basics of ecology and the interdependence of planetary life. Even sympathetic viewers, who noticed his artistic mastery, thought he was a late romantic and missed his message. But that did not perturb Ramachandran, used to ploughing lonely furrows. He kept reiterating the possibilities beyond the modernist model of progress.

The educator’s stubbornness noticeable in Ramachandran’s approach was not accidental. He taught at Jamia Millia Islamia for 27 years and, as a teacher, played a significant role in transforming the worldviews and life perspectives of his students. His pedagogic vocation also spilled into the brilliant books he wrote and illustrated for children. By using folk styles like Madhubani, Paithani, Warli and miniature paintings to illustrate them, he endeavoured to reconnect a new generation of Indians to their visual traditions.

Ramachandran was a modernist, but one open to the unexplored possibilities of tradition. Unlike most artists who addressed social issues, he kept his sense of humour alive, even if it turned black occasionally. Above all, he believed in the continuity of human truths and valued it more than professional success. He also believed in living his life as an artist and worked every day for 65 years. This makes him a rare artist who needs to be remembered and celebrated.

The writer is a critic, art historian and curator

© The Indian Express Pvt Ltd

First uploaded on: 13-02-2024 at 07:45 IST