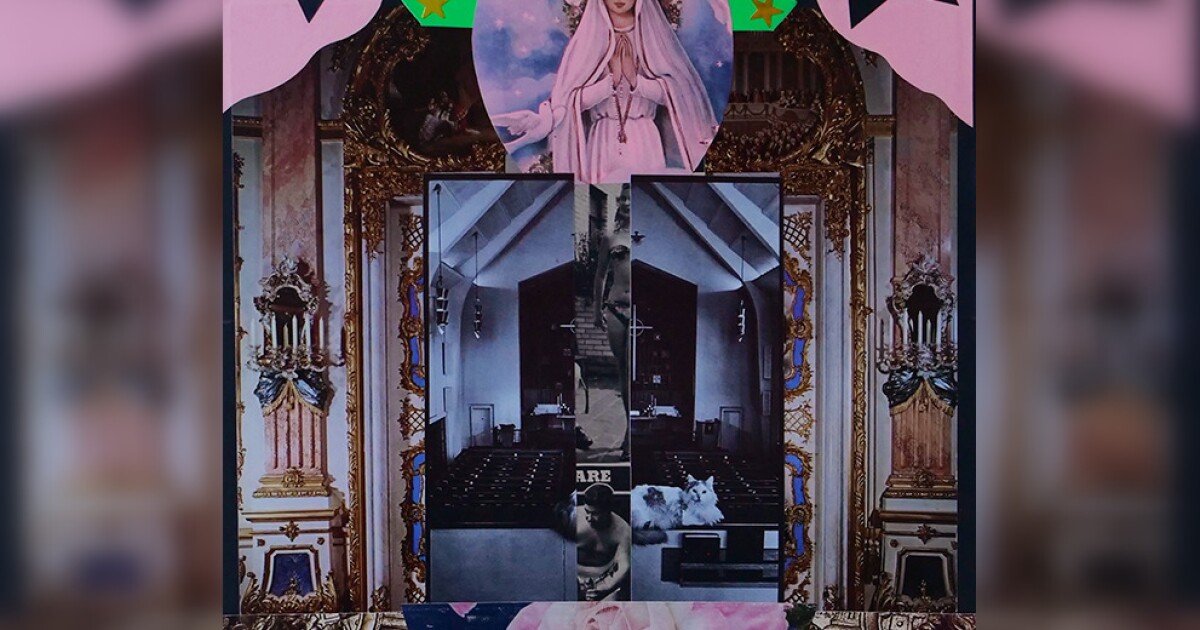

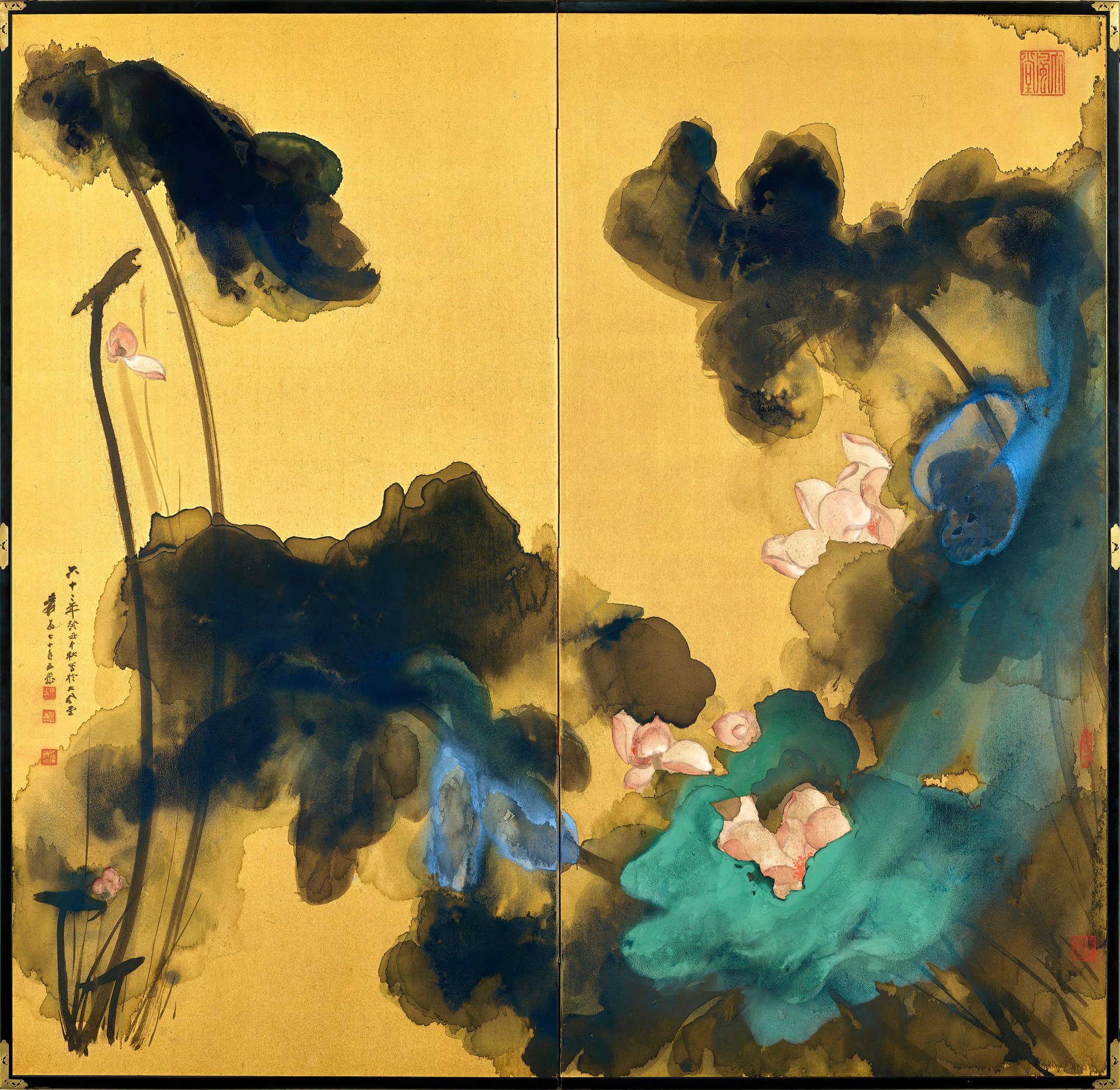

His name was Chang Dai-chien – or Zhang Daqian, or Chang Ta-chien, depending on your language or your newspaper’s style guide – and he was acclaimed for his wide-ranging oeuvre that encompassed everything from gongbi (a realist Chinese painting technique involving meticulous brushwork) to traditional Chinese ink wash and splashed-colour paintings (called pocai) reminiscent of abstract expressionism.

But not all of his works were attached to his own name – the artist was also proud to call himself a master forger, and many of his works were acquired by museums as originals.

A connoisseur of culture, Chang is widely credited as being the most prominent artist to introduce Chinese painting to the West, and his works continue to command outstanding prices at auction – the result of a growing Chinese art market and buyers who are increasingly recognising the painter’s genius.

Most recently, in December 2023, a Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction of Chang’s works from the Mei Yun Tang collection brought in a total of HK$295 million (US$37.7 million), with Autumn Mountains in Twilight (1967) – a splashed-colour depiction of the Yosemite peaks – fetching HK$199 million.

A year earlier, the auction house sold Landscape after Wang Ximeng (1948) for HK$370 million, setting an auction record for the artist and a record for the most valuable Chinese painting and calligraphy to have ever been sold by Sotheby’s worldwide.

But despite his illustrious career and acclaimed works, many details of Chang’s life remain mysterious. While it is widely known that the artist was born in Neijiang, Sichuan province, studied textile weaving and dyeing in Japan with his brother Chang Shan-tse (also written as Zhang Shanzi), and built his career in Shanghai and Beijing, his subsequent time in South America and the United States, as well as his extensive accomplishments and exhibitions in Europe, has remained largely unexplored.

A new documentary, titled Of Color & Ink: Chang Dai-chien After 1949, is lifting the veil on Chang’s overseas life, tracing his journey from China to Argentina, Brazil, California and Taipei.

Directed by Zhang Weimin, a film professor at San Francisco State University in California, the project is the culmination of a transnational 12-year journey.

The cities in which the film has garnered accolades also reflect Chang’s travels: most recently, it won the audience award for Best International Documentary at the 47th São Paulo International Film Festival, and the Best Feature Documentary award at the 20th Guangzhou International Documentary Film Festival.

‘Looking for my childhood’: Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara on why he paints

‘Looking for my childhood’: Japanese artist Yoshitomo Nara on why he paints

The film’s official premiere was held on December 8 at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, which is fitting, seeing that Hong Kong was where an exiled Chang spent months waiting to see family members.

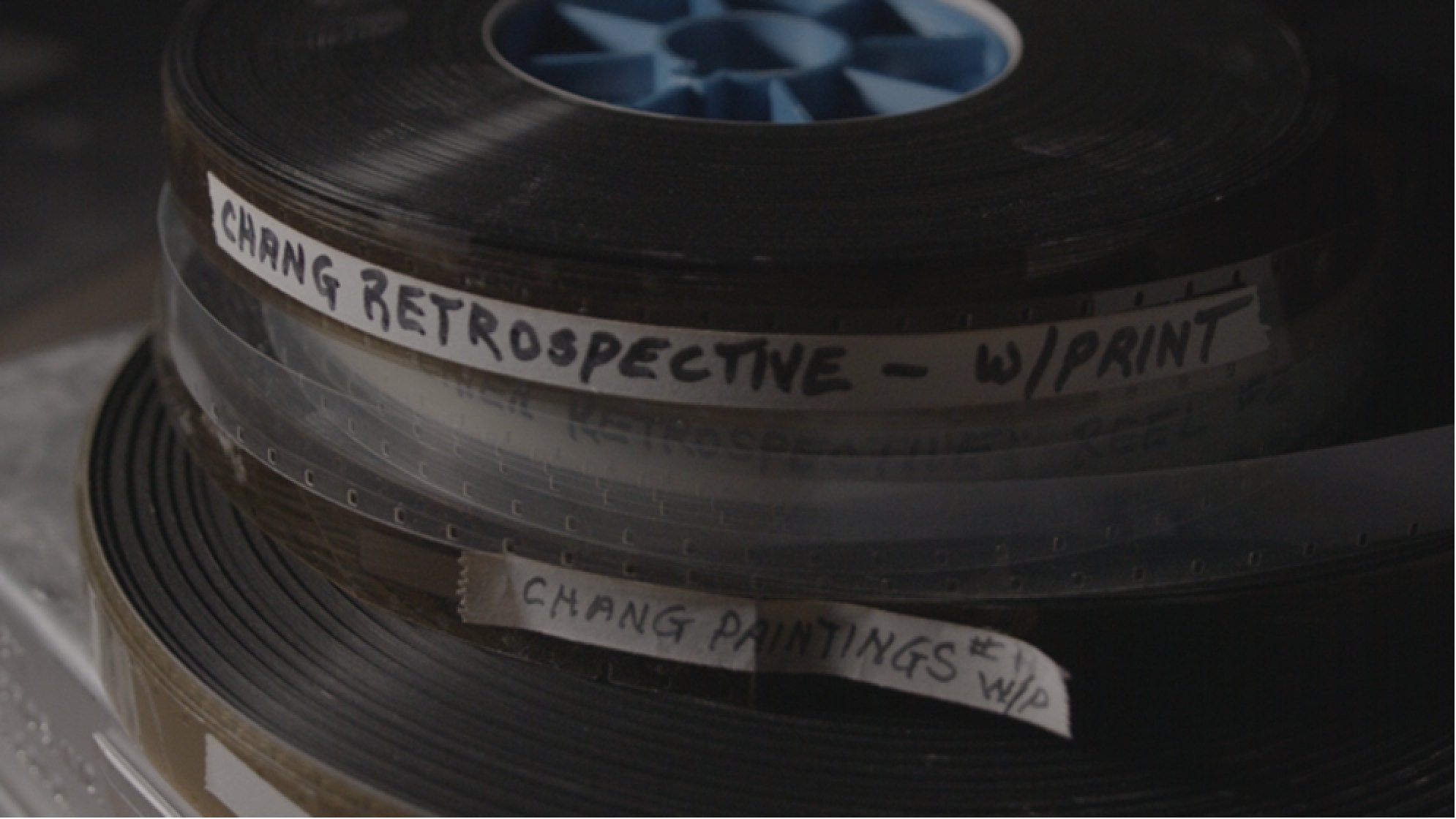

Zhang began working on the 100-minute documentary in 2011, after art professor Mark Johnson, also from San Francisco State University, passed on a pile of 16mm film from 1967 that contained footage of Chang’s time in California.

Upon watching the artist walk along Pebble Beach, she instantly felt a connection between her, the footage and Chang’s world – what she calls an inexplicable sense of yuan, or destiny.

“To me, it’s like a mission,” she says from her hotel room in Hong Kong, several days before Of Color & Ink’s premiere. “I just felt like someone had to do this. What happened to him? What happened to his life? Why is there not a complete record or history of such an important Chinese artist?”

The answer to that last question is twofold – first, there is the fact that “not many Americans can even name a Chinese artist”, says Zhang. “That’s the reason this story has been buried for so long.”

Though Chang may be well known in China, his career – at least in China’s view – is tainted by the fact that he left the motherland in 1949, just after the Chinese Communist Party wrested control from the Kuomintang.

As such, most references to Chang in Chinese history books are limited to his accomplishments before that fateful year, and he was never regarded as one of China’s Four Great Academy Presidents (pioneers of modern Chinese art).

“Like many in the past, the literati choose to leave because they were not happy or satisfied with what was happening politically,” says Zhang. “In Chinese history, they will say he probably abandoned China.”

But while Chinese history books may be unforgiving, the director counters that the decision wasn’t quite so simple for Chang, and that despite his leaving, he had a deep fondness for China, and hoped to take some Chinese culture with him wherever he went.

Upon leaving his homeland, the artist spent a year and half living in the Himalayan foothills of Darjeeling, India.

“When he went to India, it was already a bit chaotic in China, but he still wanted to come back and assumed it would be better after a while,” explains Lillian Xiao, Chang’s granddaughter. “But after a few months, once he’d held an exhibition in India, he went to Hong Kong and probably saw a lot of people leave China through there.”

Found among rubbish on a New York street: the mystery of a masterpiece

Found among rubbish on a New York street: the mystery of a masterpiece

Using funds raised through selling paintings from his personal collection of Chinese masterpieces back to China – including The Night Revels of Han Xizai, by 10th century artist Gu Hongzhong – Chang set sail for Argentina. Insights into his mindset at the time can be gleaned from his paintings and their inscriptions.

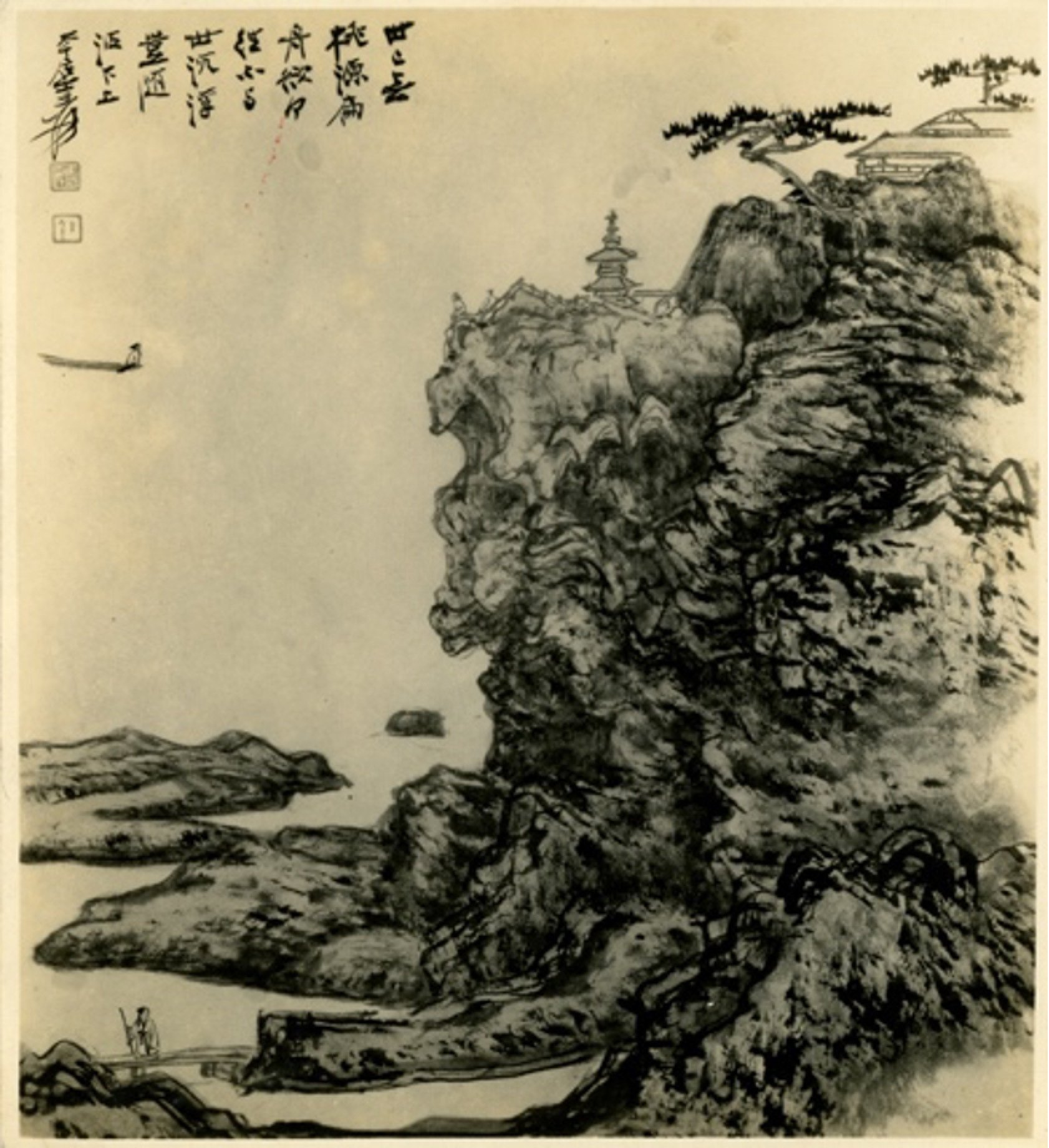

“I’m not going up and down with the waves. I’m not going to follow the trend. I’m going somewhere else, further away,” Chang inscribed on Peach Blossom Spring (1951), which features a boat on the edge of the composition – unusual for Chinese paintings, says Zhang.

“He’s turning back to look at his hometown, but he’s choosing to portray the single-plank bridge – that means he never wants to turn back.”

Chang arrived in Mendoza, Argentina, in 1952, and would stay there for two years with his wife, Hsu Wenpo (also written as Xu Wenbo), seven children and three nephews. In his lifetime, Chang had four wives (Hsu was his fourth) and 16 children, some of whom were able to leave China and accompany their father on his travels while others were held up by strict regulations at the Guangdong border.

Unable to receive permanent residency in Argentina, the artist headed to Mogi das Cruzes, in São Paulo, Brazil. There, he began his search for a physical and spiritual utopia, inspired by Tao Yuanming’s AD421 poem Peach Blossom Spring, what Zhang calls “a fairy tale built into the Chinese intellectual’s mind”.

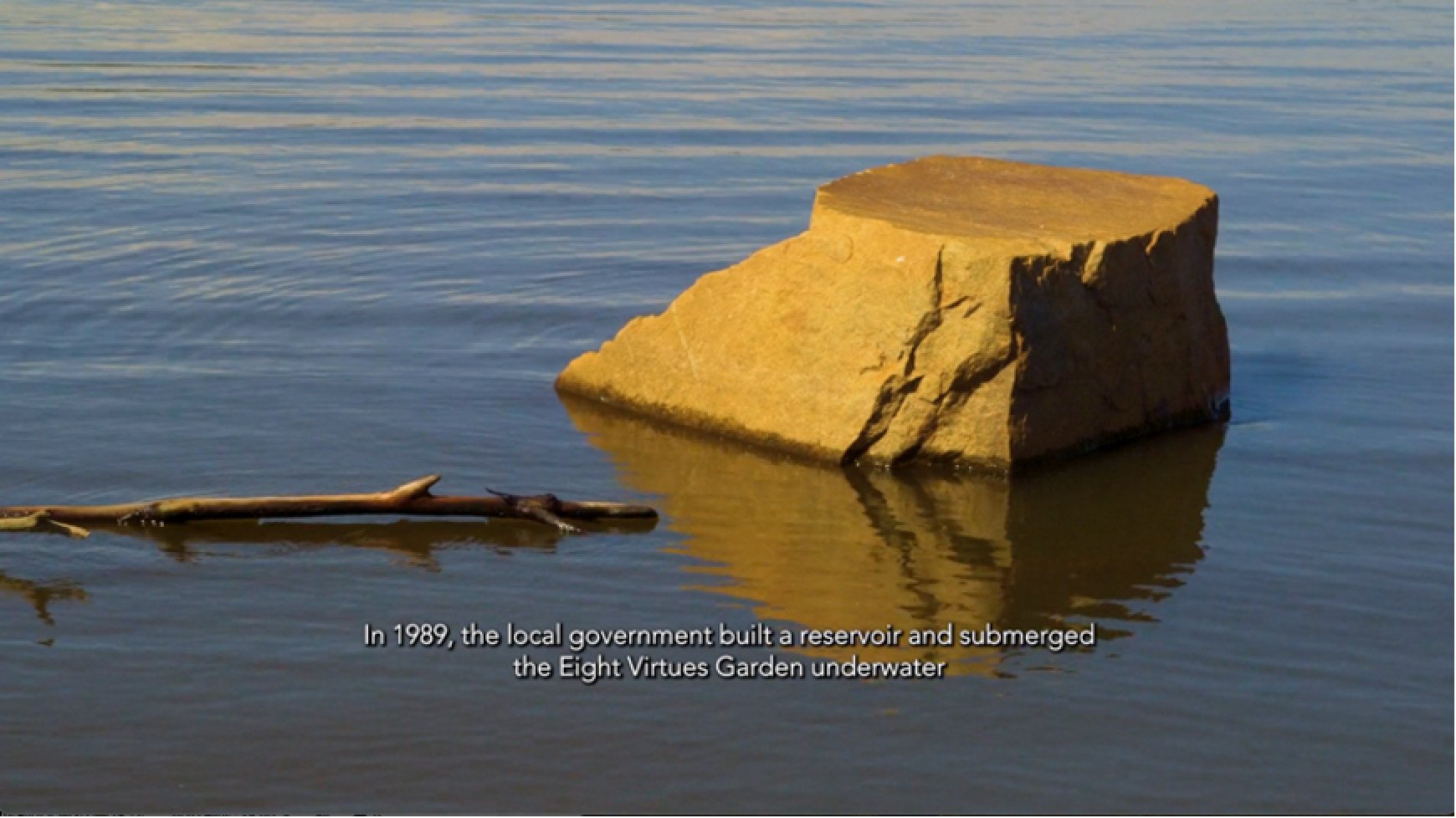

As such, Chang bought a patch of land in Taiaçupeba and began building his idyllic Eight Virtues Garden, complete with pavilions, miniature mountains, a bridge, rhododendrons and plum blossoms, persimmon trees, and a fish pond.

The artist also kept a host of pets there, including dogs, cats and gibbons. (The Eight Virtues Garden is now submerged by a reservoir built by the Brazilian government in 1989.)

It was during this time that Chang became the first living Chinese artist to be granted solo exhibitions in Europe, at museums such as Musée Cernuschi, and the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris.

He also met Pablo Picasso and André Masson in what were described as summits between Eastern and Western art, and was featured in numerous newspapers.

His success in Europe could largely be attributed to his relationship with Kuo Yu-shou (Guo Youshou), who had been minister of education under the Nationalist government before settling in Paris and becoming Unesco’s assistant director-general for education.

With his extensive connections, Kuo was able to help expand Chang’s artistic network and influence, and their close friendship meant that whenever Chang was in Paris, he would stay at Kuo’s apartment.

The artist, however, would eventually stop returning to the city after Kuo was accused of being a spy, arrested in Switzerland and sent back to China in 1966.

There’s this reverence for the past that is built into the whole tradition of Chinese painting. Chang Dai-chien was not the first forger

Carl Nagin, professor of writing and humanities, San Francisco Conservatory of Music

But what Of Color & Ink doesn’t explain is how Chang’s career was as controversial as it was celebrated in the Western world. Although the painter may have been widely respected as the first 20th century Chinese painter to achieve international recognition, his career was marred by his many forgeries, which included dozens of copies of Shi Tao’s works that he had made in Shanghai.

Carl Nagin, professor of writing and humanities at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, first came across Chang’s work when he was writing an article for The Boston Globe’s Sunday magazine about the alleged forgeries acquired by the city’s Museum of Fine Arts.

“I knew him from this very nefarious side,” says Nagin. But upon speaking to experts, Nagin soon realised that the topic at hand went beyond scandal, and that the concept of forgery was seen through different lenses in the East and the West.

“When you deal with questions of forgery, when you deal with questions of connoisseurship, there’s the question of the quality of the painting, and there’s the question of the authenticity. Two different things, especially in Chinese painting, because for centuries, Chinese painters have been copying old masters.

“If you look at it from a Confucian perspective, all the great work was done in the past. The best you can do is imitate, maybe reinvent. But you really have to copy those old masters, to get the spirit of the brushwork, to understand the tradition. So there’s this reverence for the past that is built into the whole tradition of Chinese painting. Chang Dai-chien was not the first forger.”

Indeed, Chinese literati were asked by rulers to copy paintings from the imperial collections because they were worried the originals would be stolen. But Chang was on another level.

“Chang Dai-chien was a man who was capable of copying, painting in the manner of painters from the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing, all the way up,” says Nagin. “He knew the vocabulary, the history of classical Chinese painting. As a painter, he’s like Franz Liszt.

“He knows the materials of Chinese painting, the old silks, inkstones, the seals; he writes poetry. He does gongbi-style painting, he does splash colour, splash ink. There is not a single variation or a single type of Chinese painting that he doesn’t know.”

Despite the fact that he lived in self-imposed exile, in his art and in his activities, the artist never abandoned China.

“He is the most important figure in the transmission of Chinese painting outside China,” says Nagin, who is writing the first English-language biography of Chang. “I can think of no other person who plays that role as a painter, as a collector, as a connoisseur, as a forger – all of those things, he brings to the West.

“You know the Buddhist monk [Xuanzang] who goes to India to bring back the sacred scrolls? Chang takes the sacred scrolls and brings them to the West. That’s his journey.”

Though Chang never returned to mainland China, for reasons the film never explains, the artist bore a deep nostalgia for his home country. He frequently wrote to family members who remained in mainland China, and continued to hope that the central government would allow them to see him, and not necessarily in the West, but at least in Hong Kong.

Eventually, in 1963, one of the daughters from his marriage to second wife Huang Ningsu, Zhang Xinrui, was given permission to enter Hong Kong, and was allowed to bring one of her own daughters, so she chose her youngest, Lillian Xiao, as she was not yet in school.

These amazing clay works will crumble right in front of your eyes

These amazing clay works will crumble right in front of your eyes

The trip followed a failed 1952 attempt by Chang’s daughter to enter Hong Kong through Guangdong, when she and her eldest daughter had spent months waiting in Guangzhou as Chang solicited friends to help get them across the border, but his efforts proved futile.

Fast forward 11 years, it was the government’s United Front Work Department – the department in charge of gathering intelligence and garnering influence over prominent individuals outside China – that granted Zhang Xinrui and Lillian Xiao permission to enter Hong Kong.

“Of course, it’s a conditional permission, you have to come back,” says director Zhang, adding that the implication was that the visit might convince Chang to return to China (instead of getting his family members out of Communist China via the British colony).

“That was the goal,” she says. “[Zhang Xinrui] didn’t even tell me directly, because people who lived in China through the Cultural Revolution, they know what to say, what not to say. But I knew, because I know how that works.

“You would not have got permission to go overseas in 1963. Think about the timing – China’s still going through this revolution. No one can go out, no one can go in. But, why let her go? It’s a special permission.”

While this trip is covered in the film, the special permission, and its ramifications, are rather glossed over. Xiao recalls the rampant speculation and hostility that surrounded the visit: one day in Hong Kong, she was handed a newspaper with an article about Chang that claimed his granddaughter’s mouth – referring to Xiao – was full of Communist propaganda.

“My mother was very upset. She said, ‘This newspaper is blaming us.’

“My parents worked at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, and when my mum left, leaders and officials from the institute and from the United Front Work Department did say things like, ‘Your father should come back.’

“I think them saying those things was their duty. But from my mother’s point of view, it was just about seeing her father after years of not seeing him. She didn’t think about anything else.

“In actuality, I think it was all politics. From our perspective, what we valued was family. We didn’t think much about the political side. If other people had that plan or intention, that’s their issue.”

In Hong Kong, father and daughter were finally reunited after more than a decade apart, but Chang didn’t feel the meeting was long enough. So the artist pulled in favours and arranged for his daughter and granddaughter to receive passports to leave Hong Kong.

“At the time, China and Brazil had no diplomatic relations,” Xiao says, explaining that she and her mother entered Hong Kong on People’s Republic of China identity cards but could not use those to enter Brazil. Instead, they entered South America using Taiwanese Republic of China passports.

In Brazil, Xiao and her mother frequently accompanied Chang on his daily strolls, and sat beside him as he painted. “My deepest impression was that my grandfather was really happy,” Xiao says. “He really valued Chinese tradition and respect. But looking at the video [in the film] – I was so naughty, wearing and playing with my grandfather’s hat.

“He couldn’t bear to let us go, and under that circumstance, he was especially loving and tolerant towards me. If not for that, how could I have openly ignored family rules like that? Normally, that would not have been allowed.”

Indeed, while others may have seen a dignified, serious man in Chang, Xiao saw the loving, caring side of her grandfather.

Aside from showering her with clothes and gifts whenever he returned from his travels, he also painted pictures for his granddaughter, one of which was of her favourite pet in Brazil – a black and white cat – and another of a bird, for which Chang joked that he would only give Xiao half the painting, though he eventually gave her the complete artwork.

“My mother and I leaving was becoming a reality,” Xiao says. “The reason he said he would give me half the painting and keep half was because he couldn’t bear to let us go.

“If we left, my grandfather felt like he’d lost us. If we stayed, it wouldn’t be appropriate for my mother, because her family would be separated. It was that conflicting feeling – the painting represents that.”

By then, almost a year had passed, and time was ticking for daughter and granddaughter to return home, lest their family members in China have to answer for their prolonged absence.

Before they parted, all three travelled together to open Chang’s exhibition in Cologne, Germany, where the artist also celebrated his 65th birthday on a riverboat. Afterwards, Zhang Xinrui and Xiao returned to China, via Hong Kong.

Throughout her time in Brazil, Zhang Xinrui never dared to reveal to her father what the government expected of her trip, and never asked him to return to China.

“In that generation, how could you tell your father what they should do? You wouldn’t even have that thought,” Xiao says. And when mother and daughter returned to China, they never spoke of going abroad again.

“When we returned, the situation only escalated, so we wouldn’t dare have the idea to go back,” says Xiao. “Now, it’s all open, but at the time, we couldn’t even mention it. Because, first, my father didn’t return. Second, very soon it was the end of 1965 – in 1964, there was a lot of conflict already, and in 1966 the Cultural Revolution began.

“You wouldn’t even think about leaving the country. If you thought about leaving, something would happen to you.

“At the time, they called Chang a traitor. That was a very, very serious offence.”

In the late 1960s, Chang left Brazil and moved to Carmel-by-the-Sea, in California, then to nearby Pebble Beach, before finally settling in Taipei, Taiwan, in 1978. There, he continued his search for Peach Blossom Spring by building the Abode of Illusions, a Chinese garden of plants, flowing water, pavilions and bridges.

Chang died in Taiwan in 1983, aged 83.

In making the film, Zhang Weimin says her process was independent, but when asked if there was anything she wishes she could have included, she admits that “the historical backdrop – that is a little compromise. But it’s not necessarily going to affect my whole story.”

When the director talks about “compromise” she means she faced time constraints when making the film, but it is clear that self-censorship for the sake of the Chinese Communist Party is at play.

The director’s goal with the film was to finally unite Chang with his homeland. The fact that the film premiered at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, a venue specifically designed to promote Chinese soft power in the city and beyond, shows where the film’s loyalties lie.

For example, the film refers to the Great Chinese Famine (1958-1961) – during which some 30 million people starved to death and Chang had sent sugar, peanuts, peanut oil and red dates to his family – as a period of “natural disasters”, and does so through archive audio, even though Liu Shaoqi himself, then the chairman of the People’s Republic of China, acknowledged in 1962 that it was Mao Zedong-made errors that were mostly to blame for the famine.

“If Chinese people understood the history, they already understood even without me saying,” says the director. “If Western people don’t understand, even if I provide that detail, they probably still don’t get it.”

Still, that period of time could have easily been referred to as what it really was – a Great Famine – and that would be a far more accurate descriptor for audiences who didn’t have prior knowledge of this history. But that’s not the only example of a propaganda-friendly plot hole.

For starters, there is the reality that the entire film is based on a Chinese artist who left China in 1949 – as the film explains, like “many others” at the time – but never delves into why he left or never went back.

That, coupled with the special permission Zhang Xinrui needed to leave China, begs the question of whether the film was edited with Chinese censors in mind, to avoid the risk of it not being screened in China, but Zhang asserts that was not the case.

“I don’t care who is going to interpret it in what way,” she says. “I didn’t want to accept funding from the government because I didn’t want to represent any political parties or any government perspective.

“I wanted to look at the global perspective, not worry about political interpretations from any side, because I’m not making this film for anything political. I want to make this film for history, for future generations.”

Of Color & Ink: Chang Dai-chien After 1949 is screening at Golden Scene Cinema in Kennedy Town on selected dates. For more details, visit the Golden Scene Cinema website.