Cast your mind back over the biggest pop cultural moments of the past decade or so. There’s a high chance set designer Es Devlin was pulling the strings.

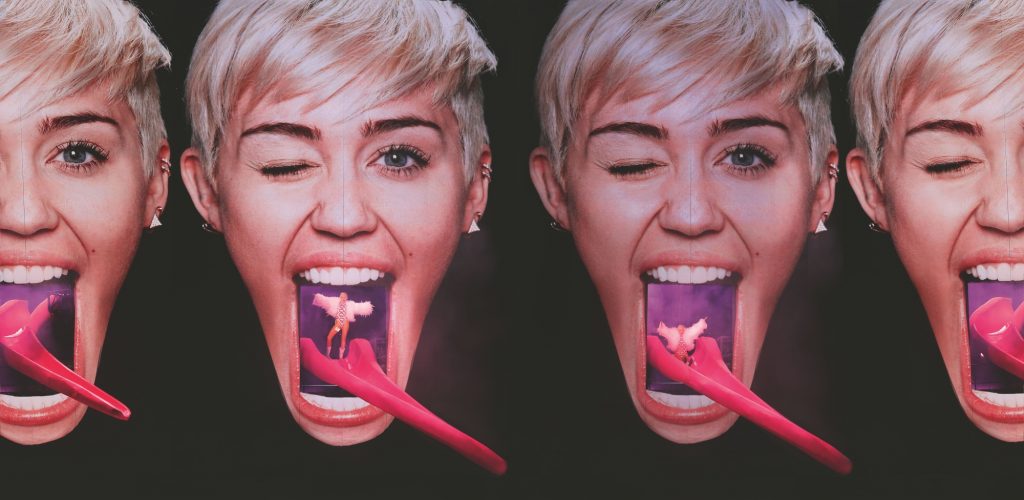

Remember Beyoncé’s most recent stadium tours Renaissance (2023) and Formation (2016), Kanye West’s Yeezus (2013), or Lady Gaga’s Monster Ball (2009)? She was also the creative mind behind the infamous lolling tongue slide that Miley Cyrus descended to a chorus of ecstatic screams during her 2014 Bangerz tour.

Tongue slide designed by Es Devlin at Miley Cyrus’s Bangerz tour in 2014. Photo courtesy of Es Devlin Studio.

Before these titans of entertainment began vying for her impeccable eye, Devlin earned her pedigree at theaters and opera houses across Europe from the mid-90s. Always at the vanguard, she became known for pushing new technologies to the limit. She made LED cubes appear to hover for Kanye and Jay-Z. For Mozart’s Don Giovanni at the Royal Opera House, she used an encoder to keep a projector streaming video content onto a revolving cube.

By the time she was profiled in The New Yorker in 2016, Devlin was heralded as “the world’s foremost set designer,” and following a dizzying list of high-profile international engagements from the opening ceremony of the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro to a Louis Vuitton fashion show in Paris, “one of show business’s busiest people.”

When I met Devlin last month at the cosy studio in her south London home, the thrill of pulling off ever more jaw-dropping feats seemed to be subsiding. The achievements of the past three decades have just been catalogued in An Atlas of Es Devlin, a robust monograph and accompanying retrospective at the Cooper Hewitt.

“Having done these giant, collaborative, beasts of revolving buildings that traveled the world and had a lot of pressure on them commercially, it’s a real relief to put those in a book,” she said of these large scale commissions.

Lorde’s performance for album “Melodrama” at Coachella 2017. Photo courtesy of Es Devlin Studio.

Now, she is ready for her next chapter.

“I think there’s something about being a woman at 50 that shifts you into another gear,” she explained. “You’ve reached the middle of your life. There’s sort of nothing to lose. It’s a good place to get started.”

Girl in a Box

Dressed in a loose yellow shirt and matching crocs, Devlin drew my attention to a through-line in her varied career: a drawing she made as an 18-year-old in the late 1980s. The blue-tinged image of a girl curled up inside a box is a more accomplished version of the kind of moody sketches that litter many teenage bedrooms.

“This person within the frame of a box is very much what I’m still dealing with,” she said. It is one of the trademarks that have made her work so distinctive, imbuing an otherwise technically cutting-edge practice with a sense of timeless cohesion. It is what ties the curtain of rain enclosing Adele during her 2016 arena tour to the party inside a tank for Lorde’s performance at Coachella in 2017 to her Tony Award-winning set for The Lehman Trilogy (2018).

The other key to understanding Devlin’s aesthetic is what she describes as her earliest memory, that of accidentally falling into the River Thames and nearly drowning. The sliver of light that reached down from the water’s surface, “penetrating a medium other than air,” reappears everywhere in her work.

Seven-minute dance work by choreographer Sharon Eyal with music composed by London-based duo Polyphonia, performed in Es Devlin’s multi-media work Surfacing (2024), commissioned by BMW at Art Basel 2024. Photo: Enes Kucevic, © BMW AG.

All of these elements merge in Devlin’s latest installation Surfacing, produced in partnership with choreographer Sharon Eyal, commissioned by BMW, and unveiled this week at Art Basel. At first glance, it appears to be just another art-filled booth, until the back wall suddenly cracks open to reveal a secret annex containing a box of streaming water. More surprises await, as various tricks played with two lines of light create the impression that five dancers have suddenly teleported out of the ether. They perform then abruptly disappear.

Devlin has also designed the blue-brushed exterior of a pilot fleet of BMW iX5 Hydrogen cars, new age vehicles still in development that will run on hydrogen.

Sublimating Her Story

Born in 1971, Devlin grew up in the coastal town of Rye, south of London. Her earliest inspirations were mostly pop cultural; the album cover for Kate Bush’s The Kick Inside (1978) prompted her to paint a Japanese-inspired mural over her bedroom wall. By her late teens, Devlin began visiting museums, and the influence of modern and contemporary artists like Bill Viola, Bruce Nauman, Rose Finn-Kelcey, Joseph Cornell, and Rachel Whiteread are evident throughout her work. Less immediately obvious is her fascination with the peculiar perspective boxes by 17th-century Dutch painter Samuel van Hoogstraten or the luminous gold ground on the tiny, devotional Wilton Diptych.

Despite showing serious promise in art classes at high school, Devlin initially studied English Literature at Bristol University. “I didn’t feel I had anything to say,” Devlin mused. She was 22 when she began her foundation year at Central Saint Martins, where “the diagnosis on me was, ‘you’re interested in music, you should do theater design.’ But I had only been to the theater a few times. I found it quite boring,” she said.

Es Devlin’s stage design for The Lehman Trilogy (2018). Photo courtesy of Es Devlin Studio.

Nevertheless, when Devlin enrolled at the prestigious Motley Theatre Design Course she immediately felt at home in its 24 hour studio filled with miniature models and a cohort that stayed up all night listening to opera while they worked. Though she remembers feeling energized by that decade’s craze for YBAs like Damien Hirst, for whom she briefly worked, Devlin was intrigued by the potential of ephemeral work that wasn’t for sale. “Really, the work would happen in the minds of people watching it and they carry it forth.”

Moving from theatre productions to stadium tours in the mid-2000s was an exciting challenge because while theater has been evolving since ancient times, the concert was a nascent art form. The intimacy conjured by a televised performance of The Beatles didn’t translate to the stage at Shea Stadium in 1965. “It ended in chaos,” said Devlin. “No one could see or hear The Beatles who were not safe, were not protected from the onslaught of hunger. There was no architecture to mediate this kind of encounter.”

Devlin has since harnessed emerging technologies to create a spectacle in which our favorite stars inhabit fantastical, futuristic planes but are never swallowed up by them. “As we become enamored with the pixel, I think there is an underswell of desire to converge physical matter with digital,” she said.

Beyoncé’s “Renaissance” tour from 2023. Photo courtesy of Es Devlin Studio.

The question Devlin most often gets asked is whether she minds adapting her ideas to the aims of a bigger ego. “I’m really interested in seeing through the eyes of another,” she said. “I’m actually quite happy to lose myself for a bit, to sublimate my own story.”

Outside of the Box

That story, however, has now become central to Devlin’s work, as she has decided to focus on more personal projects over the past few years.

“This rough magic I here abjure,” she said, quoting Prospero from a speech in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, widely interpreted to mirror the playwright’s own feelings as he let his quill rest on the last full play of his lifetime.

While Devlin has no plans to cease producing her rough magic onstage, she has been summoning the courage to do what she never could at 18. “I didn’t go to art school then because I didn’t feel I was able to catalyze my poetry, my pain, my experience into art,” she said.

Es Devlin, Come Home Again (2022) for Tate Modern. Photo: Daniel Devlin.

The flow of our conversation was twice interrupted by Devlin’s wonderment over the appearance in the garden of an urban-dwelling animal most observers would consider mundane: a magpie and later a squirrel. She shows me her sensitive studies of wildlife, from the Kingfisher bird to the humble leafhopper.

These creatures congregated in 2022 for Come Home Again, a brightly lit, dome-like structure outside Tate Modern bursting with drawings of some 243 species that call London home. In another drawing, for the Serpentine Galleries, the contour of a hand morphs into the outline of insects, plants, and birds, speaking to an unbounded connection with the biosphere. It’s the inverse of the melancholic image of containment that Devlin drew at 18, and a cathartic bookend to that line of inquiry.

Es Devlin, Re-draw The Edges of Yourself (2022) made for Serpentine Galleries. Photo: Daniel Devlin.

“Each encounter with another being is a portal onto the universe seeing itself through another form,” said Devlin, her register stepping up a notch with enthusiasm. “It’s such a privilege.”

Lining the far wall of her studio are some fifteen sketched portraits of refugees that will be presented outside St Mary le Strand church during London’s Frieze week this fall. She describes them as “a work about porosity, between ourselves and others.”

It’s a move not many would expect from Devlin, but it’s time we start looking at her practice through fresh eyes. After decades spent using her talents to help other artists realize their visions, she has finally broken out of the box.

Commissioned by BMW, “Surfacing” is at Art Basel until June 16. “An Atlas of Es Devlin” is on view at the Cooper Hewitt through August 11.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: