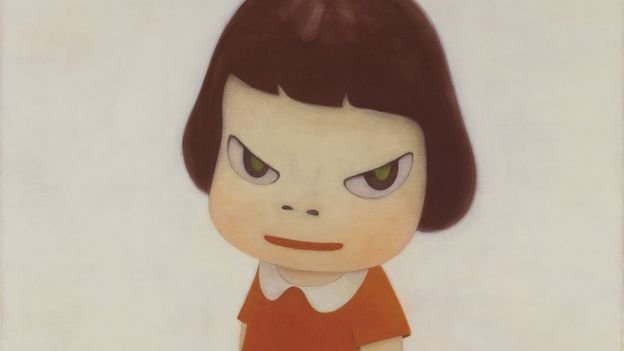

(Image credit: Courtesy of Sally and Ralph Tawil/ Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

How Japan’s “most famous” artist, and others, are subverting the country’s cute “kawaii” aesthetic to question the world we live in.

M

More than a millennium ago, the Japanese empress Fujiwara no Teishi gifted one of her court ladies, Sei Shōnagon, a bundle of fine paper. Sei, who was from a literary family, used the pages to jot down observations from her daily life in a collection now known as The Pillow Book (1002). In one section, Sei wrote a list of “adorable” or “utsukushi” things, from “hopping” baby sparrows to a child “clinging to someone who has picked him up” to simply “anything small”.

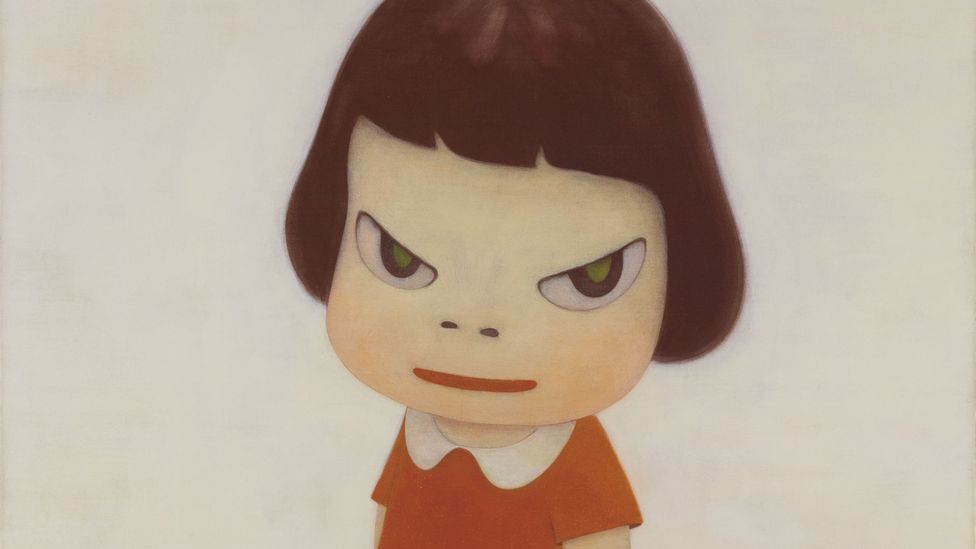

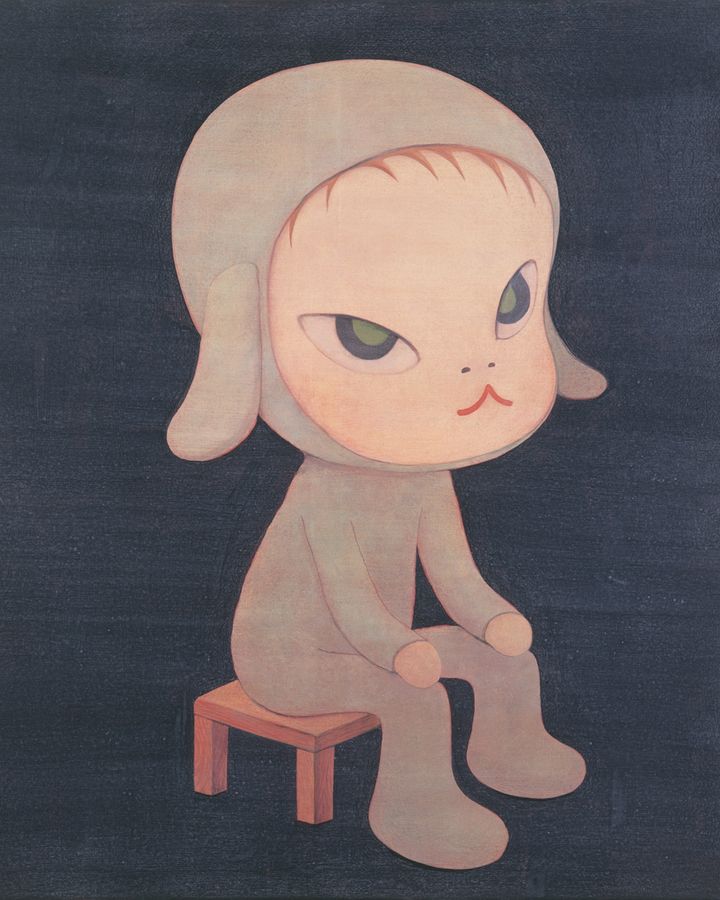

Sleepless Night (Sitting) (1997) – Yoshitomo Nara’s figures deviate from conventional ideals of childlike ‘cuteness’ (Credit: Rubell Museum/ Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

While today, the book is seen as a window into Japanese nobility during the Heian Period (AD794-1185), Sei’s idea of what is utsukushi still resonates with people today and is seen as one of the earliest examples of Japanese “kawaii” culture, though the term “kawaii” which translates to “cuteness” was not a part of the country’s lexicon at the time. “All of the items on the list are things that we would find cute today, which is remarkable because society was really different 1,000 years ago in Japan,” says Tokyo-based professor Joshua Paul Dale, who specialises in cute studies at Chuo University. “It ends up being a significantly complete documentation of a cute aesthetic that existed even before the word cute did.”

Kawaii, as we know it today, began in Japan around the 1970s and has since become a world-renowned phenomenon, recognised globally for its colourful, childlike aesthetic found in fashion, art (especially manga), and everyday memorabilia. But, as the trend has expanded, a wave of contemporary artists in the country have used aspects of cuteness to create paintings that probe various facets of society or grapple with personal, national or global trauma. “There are a range of hybridised categories that experiment and disrupt cute aesthetics,” says Dr Megan Catherine Rose, a cultural sociologist at The University of New South Wales in Syndey, mentioning that these emotionally complex artworks often bring “together seemingly disparate expressions to give voice to the dissonances that emerge in everyday life”.

The artist Yoshitomo Nara seated in front of his artwork TOBIU (2019) (Credit: Ryoichi Kawajiri/ Courtesy of the artist/ Blum & Poe/ Pace Gallery/ Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

One of the most prevalent examples of such paintings is Knife Behind Back (2000) by the Japanese painter Yoshitomo Nara, which sold for just under $25 million at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong in 2019. Nara has been described as “arguably, the most famous living contemporary Japanese artist”. The painting depicts one of Nara’s most identifiable portraits, a small, doe-eyed girl with short brown hair in a red dress and sporting an almost threatening frown. The piece is part of an extensive collection of similar works Nara has made over several decades. “The Nara ‘girl’ is a contrary figure,” writes art historian Yeewan Koon in the 2020 monograph, noting that Nara has created “a band of big-headed figures who behave in ways that deviate from conventional ideals of cuteness with their aggression, irreverence and wit”.

Articulating emotions

According to Nara, while it may not be apparent simply from viewing his work, he is continuously influenced by “things that have nothing to do with the art”, he tells the BBC on the opening day of his retrospective Yoshitomo Nara, showing at the Guggenheim Bilbao, in Spain, until November. Instead, Nara finds inspiration from his ventures “like visiting Syrian refugee camps or going to Afghanistan”, he says, explaining that in the ’90s, he made roughly 120 paintings a year, using his practice to articulate the emotions he struggles to put into words. “I began by remembering the feelings and emotions of my childhood, but gradually, I started looking further afield, learning about society and travelling to various places.”

The recent Cute exhibition at London’s Somerset House explored cultural ideas around cuteness and kawaii (Credit: David Parry, PA for Somerset House)

Though Nara says that his experiences growing up were positive, his work has been greatly inspired by the isolation he felt being born just after World War Two in Hirosaki, a rural town more than 400 miles from the country’s capital, close to a US Air Force base. His two siblings were seven and nine years older than him, and, according to Koon, due to “rapid socioeconomic changes” at the time in Japan, both of his parents worked demanding jobs, so Nara was often left home alone. “Growing up as a postwar child on the geographical margins of Honshū, the main island of Japan, shaped his sense of self,” explains Koon, noting that Nara particularly “connects to those who are from or have been displaced to border regions”. Dale adds: “Artists love the complex. They usually don’t want to stimulate simple emotions in people. So [Nara] took the kawaii that was floating around everywhere in Japan and added other [emotions] into it.”

Art shaped by the postwar experience has also been associated with the Superflat movement in Japan, a term coined by the renowned artist Takashi Murakami in the late ’90s. Murakami used Superflat to describe a wave of artists merging high and low art, particularly works incorporating kawaii and manga-inspired motifs prevalent in postwar Japan. “World War Two was always my theme – I was always thinking about how the culture reinvented itself after the war,” Murakami told the New York Times in 2014. Murakami’s Tan Tan Bo – In Communication (2014) features two sinister-looking versions of the artist’s signature character, Mr Dob, a Mickey Mouse-inspired character with sharp teeth. In the Tan Tan Bo work, the character has mutated almost entirely into two monstrous type creatures with drunken eyes and dark, mountainous teeth that other beings appear to live among.

Takashi Murakami’s work was displayed at a design fair in 2020 – he coined the term ‘Superflat’ (Credit: Getty Images/ Courtesy of the artist)

According to Murakami, Tan Tan Bo – In Communication was made in response to the Great Tōhoku Earthquake and tsunami of 2011, which subsequently led to the Fukushima nuclear accident. For many artists in this country, this period served as a pivotal moment in their practice, as it provided an “opportunity for Japanese artists to contemplate the social and ameliorative potentiality of art”, says cultural researcher Hiroki Yamamoto, currently the curator of the Japan Pavilion at the 15th Gwangju Biennale. “As a result, throughout the 2010s, predominately young contemporary Japanese artists created works that critically explore the (largely forgotten) history of Japanese imperialism and colonial domination during the Second World War, and the ‘legacy’ that this history has generated in present-day Japan.”

Aya Takano, one of the most recognised artists in the Superflat movement, notes that before Fukushima, her artworks were “really shallow”. But, having now considered Japan beyond just its cities, she creates pieces that are “truly infinite and rich”. Her 2015 painting The Galaxy Inside, which was featured in Cute, an exhibition on cuteness and contemporary culture that was on show at Somerset House in London earlier this year, depicts large-eyed androgynous young women suspended in space among planets and sweet-looking animal-like creatures, some in chains – but still smiling. Her paintings, she says, explore the climate crisis, considering a world where humans and nature exist peacefully.

Missing in Action (1999) by Yoshitomo Nara is among the works currently on display at the Guggenheim Bilbao (Credit: Courtesy of Sally and Ralph Tawil/ Yoshitomo Nara Foundation)

According to cultural sociologist Dr Megan Catherine Rose, kawaii has also been utilised in this way by feminist artists in the country. “Kawaii as a gendered aesthetic has been used over the centuries to curate and present women’s bodies as beautiful objects, in a similar way to the treatment of women in European traditional art,” she says, adding that contemporary Japanese feminists often use their art to “interrogate the objectification of women’s bodies”. Rose points out the US-based Japanese artist Mizuno Junko, explaining that her “figures are monstrously feminine, designed to repel the cisgender-heterosexual male gaze through repetition, exaggeration and hyperbolic femininities”.

More like this:

• Photographs that skewer British peculiarities

• Coquette: The ultra-girly movement sparking debate

• Inside Japan’s most minimalist homes

It’s worth mentioning that while Nara has also been identified within the world of cute-but-menacing paintings, the artist himself does not necessarily agree with this association, wary of being boxed into any particular artistic canon or movement – Superflat, kawaii or cute – though he sees why others may associate him with these. “There are people out there who have been superficially influenced by my paintings, and probably think they’re cute,” he says. “They probably have no desire to go to refugee camps or participate in anti-war activities [like I have]. If I were asked to draw cute pictures, I would be able to do it, but it would be completely different from what I’m currently drawing.” What his work, alongside many others, does show is that cuteness can be used as a tool to question the world we live in, including some of its darkest moments, a practice many Japanese artists have mastered.

Yoshitomo Nara is at the Guggenheim, Bilbao until 3 November 2024

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.

;