By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The cutting edge art that gives viewers a window into the future is now on exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art. And that future looks a lot like the past.

As the Museum Director Adam Levine told those gathered for the press preview on Friday morning, many of the works in “Infinite Images: The Art of Algorithms” rely on wires to deliver data. But the museum’s staff artfully tucked those wires out of sight. It was, Levine said, “a Herculean effort.”

The show celebrates the ways artists are pushing digital technology to create intriguing works. Yet they are displayed in the Canaday Gallery pretty much the way the Rachel Ruysch’s 16th century paintings of flowers are exhibited elsewhere in the museum. Like Ruysch’s paintings these also reflect a creative collision of science and art.

Understanding the technology behind these works is daunting, even overwhelming. Appreciating the art is not.

The museum provides a brief glossary of the terms and concepts.

“Infinite Images: The Art of Algorithms” opens today, July 12, and runs through Nov. 30. Tickets are $10. Click to purchase. Museum hours are: Wednesday, Thursday, and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Friday and Saturday from 11 a.m. to 8 p.m.

While associated with digital technology, including artificial intelligence, the exhibit traces the development of algorithmic aesthetics back to time before computers were readily accessible.

The work itself is in the written instructions, the code, for creating it, explained Casey REAS in a press materials. But then it comes to life in form and color. That’s on full display in “Infinite Images” from spare video game like images to intricately detailed digital painting.

Sol LeWitt created art that could be replicated by following detailed descriptions. Among the pieces representing LeWitt’s sculpture “Corner Piece #1,” another instance of the museum setting a favorite piece from the collection in a new context. (The hallway of the Peristyle features LeWitt’s drawings, but that could not be brought up to the Canaday for the show.)

The mother of generative art is Vera Molnár, a Hungarian artist who worked in Paris. She was inspired by computing and information theory before she had access to a computer, working by hand using those principles until 1968 when she started working with a computer.

She and other artists working along these lines used dice and other devices to mix things up. “There’s one thing that can replace intuition; it’s randomness,” she said. That quote is emblazoned high on the wall above her works.

Many of the works allow for viewer interaction.

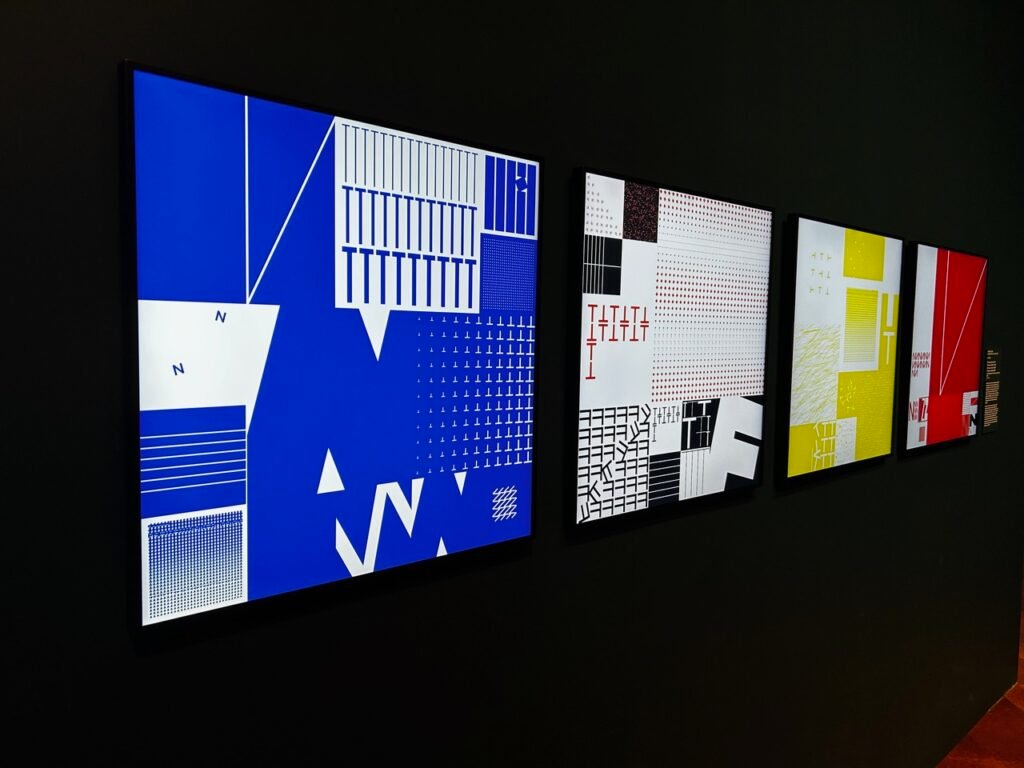

REAS’ “Century” allows viewers to digitally rearrange elements on one of 22 images. They then can display it in one of three digital frames.

Born in 1972, REAS said he straddles the 20th and 21st centuries, “Century” was inspired by the abstract artists of the mid-20th century such as Piet Mondrian, Ellsworth Kelly, and George Rickey. The museum has works by each in the collection. The latter two in the sculpture garden.

REAS started as a painter “doing everything with my hands, doing things with pigment, paints,” he said Friday.

But in his last two years of school at the University of Cincinnati, where he studied graphic design he started to work digitally. He went on to get a masters degree in media arts and sciences from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“So essentially, I’m a painter, but I work with a code,” REAS said.

He’s also an influential educator. He teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he co-directs the Social Software initiative.

Among those he has inspired is Emily Xie whose work is on the wall facing REAS’ “Century.”

Born in 1989, she is a generation younger than REAS. “He was just a pioneer in the space. … As a generative artist, he was just an example to look up to,” she said.

She has an undergraduate degree in art and architecture and a masters in computer science and engineering, both from Harvard, and has worked as a software engineer.

“I’ve always had a love for computers and a love for art, and generative art seemed the best way to combine it.”

While most of the work on display is abstract, hers verges on floral.

“It’s somewhere between abstract and representational,” she said. “I really love that space because there’s so much potential there because you start projecting your own subjectivity onto the artwork.”

The work invites the viewer to do the same.

Xie along with Daniel Hernandez will be digital artists in residence at the museum starting in Sept. 13.

The artist Quayola’s video “Jardins d’Eté (Summer Gardens)” is a tribute to the work of Claude Monet.

Jared Tarbell’s “Entity #14” is a fanciful depiction of a community of cells, inspired by bioscience.

Set off in a separate room from the other pieces is the largest, most elaborate work. Sam Spratt’s “X: Masquerade” is a large scale digital painting.

Spratt said he started as an oil painter. He has been “setting out a process of trying to figure out whether in this day and age, digital painters can create a studio that isn’t filled with a bunch of interns or assistants.”

He’s been inputting every note he makes, every sketch, under paintings, every brush stroke all with the goal of creating “clones of my own hands. trained on my own work.”

The painting a highly detailed photo realistic of the 10th scene in the ongoing saga of a character Luci. This painting comes after his wife and artistic collaborator, Rachel, gave birth to their child, who is now 11 months old.

Luci is an ape-like man. In “X: Masquerade” Luci and the mother of his child huddle in a nativity scene. They are surrounded by dozens of figures. They represent “various people as a part of the community, who then engage and involved themselves and right on top of it tearing it apart and analyzing it,” Spratt said. Masks help symbolize their motivations.

“My wife, Rachel, and I have been building this together for the last few years, and in doing it and telling the story,” he continued. “We suddenly have all the swirl of every type of person around us, ranging from the truest patrons to those that we don’t quite know what they want from us.”

In front of the painting sits a console where viewers can write reactions. Commentary to specific details are noted on the screen version of the painting.

The reactions as well as fragments from the Spratt’s poetry and journal, run down the two sides of the image.

In the video explaining his process, Spratt said, that at first there seemed a split between the warmth of the hand created work and the machine generated work. But slowly that gap has disappeared. Machines, after all, are part of nature, created from metals dug from the earth.

During the press preview on Friday, Levine emphasized that this exhibit is a continuation of the museum’s mission.

The founders Edward Drummond Libbey and his wife, Florence Scott Libbey, went to Europe and collected the contemporary art of the early 20th century. “They were contemporary art collectors. That is actually in the ethos of this institution. There is not a contemporary art museum in Toledo. We are that.”

This is the first exhibit of devoted to digital art, he said, but not the last. The museum also will continue to celebrate the art of the past, such as the Rachel Ruysch exhibit and a forthcoming show on jewelry from the 19th and 20th centuries.

As the museum engages in its first re-installation of its collection in 40 years, digital art will be “part of the conversation,” Levine said.

“We have an obligation to provide a whole portfolio of art history to our audience.”