From Les Rencontres d’Arles to Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, our editors on what they’re looking forward to this month

Les Rencontres d’Arles 2024: Beneath the Surface

Various Venues, 1 July–29 Sep

Those heading to the annual photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles will find a programme of 31 exhibitions that somehow all fit within this year’s theme Beneath the Surface – which focuses on photographic narratives that ‘lead to divergent, multiple paths, all emanating from the faults in a porous surface: they intertwine, superimpose and overlap.’ Suitably vague and yet fitting for a festival that seeps its way into all corners of the city’s historic centre. One exhibition that shouldn’t be missed is I’m So Happy You Are Here (at the Palais de l’Archevéché), which spotlights the work of 26 Japanese women photographers who have been making work between the 1950s and today. In an attempt to challenge ‘historical precedents and the established canon’ of photographic history, much of which (like many other forms of art) has long been dominated by the male lens, I’m So Happy You Are Here addresses this by presenting the ‘experiences and perspectives of women on their own lives and on Japanese history and society’ via a collection of photographs, videos, installations and photobooks. The breadth of these women’s experiences is reflected as much generationally (all but two are living) as by subject matter. Take for example, Okanoue Toshiko, who is now 96, and best known for her surreal photocollages made during the 50s that explored and poked fun at ideals of femininity propagated by European fashion magazines. Or Sugiura Kunié, who pushed the boundaries of photography in the 60s with her photo-paintings, aiming to move the medium beyond the image itself and into the material realm – later in the 80s, she became known for experimenting with light-sensitive materials, which led to the series Artist and Scientist (1999–) that included photogram portraits of figures such as artists Yayoi Kusama, Carolee Schneemann and molecular biologist Dr. James D Watson. The exhibition also includes the work of Katayama Mari, whose self-portraits challenge prejudices and preconceptions around body image via her own experience as an amputee. And Narahashi Askako is best known for taking photographs while semi-submerged in the seas around Japan; the resulting images are disorientating, leaving viewers feeling as though caught halfway between breathing and drowning. Here, these photos behave as a visual metaphor that encapsulates the state of visibility for female Japanese photographers. Fi Churchman

Dudi Maia Rosa & Anderson Borba

Auroras, São Paulo, through 15 August

Dudi Maia Rosa emerged from Escola Brasil, the ad-hoc 1970s art school. Throughout the following decade, he experimented with painterly planes of pigmented polyester resin in fiberglass – stained glass and Murano reliefs were influences – which have gradually become even more sculptural and messier in latter years, with pictorial elements such as flowers also entering the frame. A recent work features a great sheet of transparent fibreglass interrupted by a series of rough orange abstract markings; in another, that could be interpreted as a landscape, black rays stretch up from a block of green. The works have an industrial quality, with the chemical sheen of the materials hinting at darker environmental themes. But nothing feels laboured: indeed, Maia Rosa seems like he enjoyed himself making them, delighting in a Matisse-like pleasure of colour and form. Such messy elegance characterises the work of Anderson Borba too, the younger artist with whom Maia Rosa shares this two-header exhibition. Borba studied in London and lived in the British capital for a decade, so the DNA of Henry Moore or Richard Deacon might be detected in his amorphous wooden sculptures. They are more ferocious than the monuments of those Europeans however, the Brazilian’s work chiselled and scorched, a degraded quality that is powerful in its rawness, especially up close. Torso II (2024), a hunk of burned black tree trunk, has a split down the middle for example, Borba’s mends to the damage made obvious, which like the work of Maia Rosa, hint to ecological as much as bodily concerns. Oliver Basciano

Photographic Geomancy

Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou, 13 July–7 October

A specifically Chinese approach to landscape photography, according to art-historian Wu Hung, started with picturesque photomontages of misty mountains aping shanshui paintings of mythical landscapes. These photomontages came half a century after the photographic surveys commissioned by Western companies and militaries to establish trade routes or conquer geography through documentation – think Philip Egerton’s expedition through the Himalayas and Felice Beato’s panoramic shots of Dalian’s coastline from the mid-nineteenth century. Fiction and truth mingled in both these representations of the country. Photographic Geomancy, curated by Yining He, delves into contemporary photographic practices in picturing landscape – in which historical conceptions of space meet infrastructural development, geopolitics and ecology – and challenges the way traditional geographical imagination informs cultural and historical identity. In Wenxin Zhang’s photography series of Karst caverns, for example, the effect of geological time takes on physical, even corporeal shape, making the site an undulating, aspiring agent, its deep, mysterious tunnelways growing beyond territorial, anthropocentric imaginations. Yuwen Jiang

Lonnie Holley: All Rendered Truth

Camden Art Centre, London, 5 July–15 September

The late Georgia-based collector William Arnett famously described the art of the Black American South in the twentieth century as ‘the one great thing America has ever had to give to the history of visual arts’. He was speaking, of course, about his collection the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, some 1,300 works that constitute a precious fraction of this ‘vernacular art’ tradition – of works produced away from the exclusive environs of traditional art schools, galleries and museums, then displayed and sold in the region’s yard shows. One such work, loaned to the Royal Academy for last year’s Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers, was Keeping a Record of It (Harmful Music) (1986) by the Alabama born artist and musician Lonnie Holley. In it, a horse-skull is pinched in place at the centre of a record, the player beneath it bronzed by rust and mud, at once a comment on the racist suppression of Black music and a playful inhabitation of such malign stereotypes, the deathly sockets snarling back at us almost in jest. Holley, who has been producing work for forty years and is also a renowned musician, will this month feature at the Camden Art Centre, having completed a residency in the UK earlier this year. As ever, Holley’s work looks beautiful and thunderous: The Blood Was Forced but the Flag Was Free (2024) distorts the star-spangled banner into a rippling field of blues, reds and blacks, while wisps of white lines find the abstract curvature of face-profiles; Hung Out (2021) presents a series of target-practice sheets hung from a wooden domestic washing frame – what is a regular neighbourhood for some, the artist suggests, is often a gun range for others. Alexander Leissle

Hakuna Utopia?: In Search of Micro-Utopias

Various Venues, Nairobi, 20 July–20 September

Amid ongoing protests in Nairobi against tax rises and, after a lethal police response to protests, the President last week withdrawing a proposed controversial finance bill, art might not be a balm. But ‘art modifies what is held in common’, as artist Walead Beshty once wrote, and provides a chance to consider what else is possible. In a warehouse in Nairobi’s industrial area, and in four other public locations around the city, including the city’s Arboretum and in the Lucky Summer area’s Shrine park, seven artists (Ajax Axe, Stoneface Bombaa, Coltrane McDowell, Neemo Mungai, Lincoln Mwangi, Shabby Mwangi and Abdul Rop) propose temporary micro-utopias. The collective organising the exhibition, Kairos Futura, have held outdoor installations through Nairobi in recent years, with installations that envision a DIY futurism. Here, the works are pragmatically optimistic, like the small plaster maquettes of Abdul Rop’s Utopia Monuments (2024) asks audiences to stack and assemble their own miniature public sculpture, and Stoneface Bombaa’s Wearable Forest Helmets (2023), in which performers don earthen pots that sprout shrubs and saplings as part of an ongoing ‘tree mourning ritual’. Hakuna Utopia? turns the overused ‘no worries’ phrase into a challenge: can we make new worlds from what’s already here? Chris Fite-Wassilak

」-1230x923.jpg)

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

Various venues, Nigata Prefecture, 13 July–10 November

One of the biggest art festivals in Japan, Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale has been going since 2000, taking place across Niigata Prefecture, on the west coast of Honshu. It’s an outdoorsy event, spread across the 760sqkm of the ‘Echigo-Tsumari Art Field’, six regions of this mountainous prefecture, on both sides of the Shinano River, hence its ongoing commitment to art that reflects on its relationship to the natural environment. For this edition, work by over 275 artists and groups from 41 countries, including 100 new commissions, will be present. It’s a project that has steadily built up a permanent collection of sited works, such as the refurbishment and reinvention, by Beijing’s MAD Architects, of the Kiyotsu Gorge Tunnel, turning the old concrete footway into a meditation on colour, light and space, with mirror pools opening onto views of the gorge. In 2024 MAD Architects return with a strange membranous bubble that will allow visitors to stay ‘inside’ the festival’s China House venue while going ‘outside’ it; British artist Antony Gormley will be adding a new work from his Man Rock series (carved boulders resembling human figures curled up or wrapped into the rock); and Turkey’s Ayşe Erkmen will reconstruct the remnants of a dwelling collapsed in the 2004 Niigata Chuetsu earthquake, suspended in a mesh of wire. Definitely an event for those who like touring and walking, so make sure to bring hiking boots. And maybe a map and a compass. But who has those these days? J.J. Charlesworth

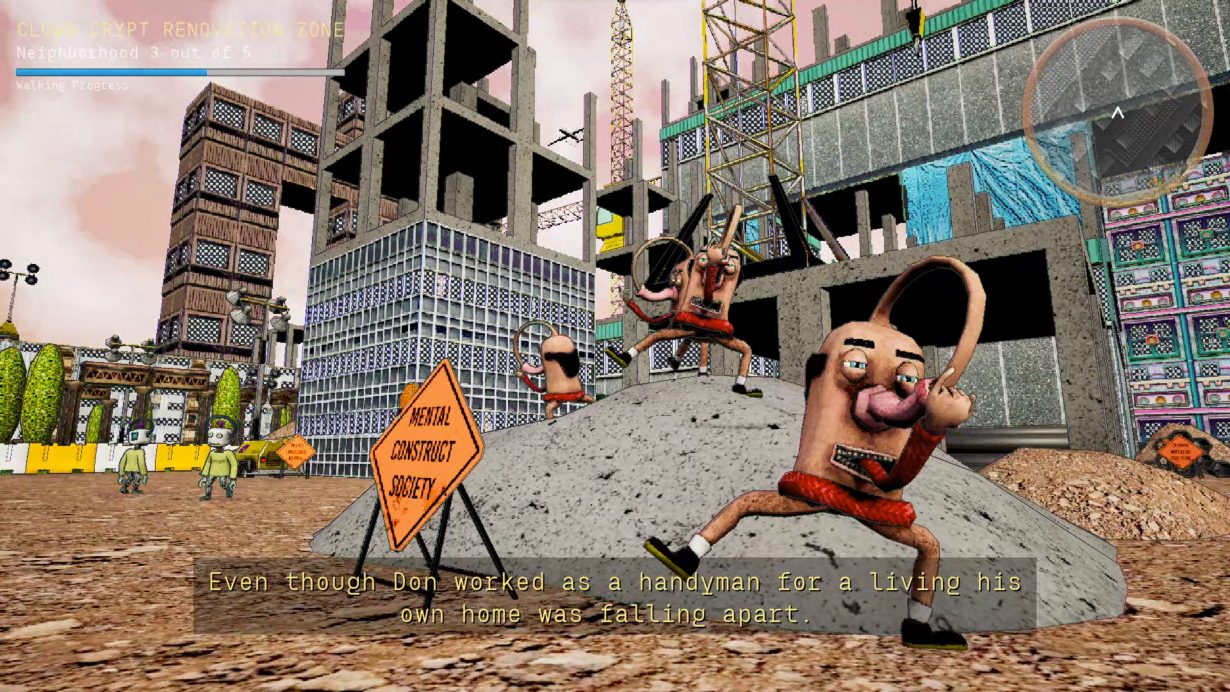

List Projects 30: Jeremy Couillard

MIT List Visual Arts Center, Cambridge, MA, 18 July–6 October

At the beginning of Fuzz Dungeon – New York-based artist and self-taught coder Jeremy Couillard’s 2021 game – a staff member at a nondescript company writes on a google doc that ‘Fuzz Dungeon’ is a place in your head where ‘a thought slowly morphs into a real life thing’, which is where great ideas go awry. (‘Good ideas turn into bureaucratic nightmares,’ the memo continues. ‘Daydreams turn into mass starvation and poverty. An entire two years of a life turns into a video game that costs 3.99 on the internet.’) Couillard was trained at Columbia University as a painter – if Fuzz Dungeon shows his somewhat self-deprecating cynicism over whether grand visions can be realised, his most recent, open-world game Escape from Lavender Island (2023) takes on an outwardly dystopian view. In the game the main character wakes up from a dream only to realise that he’s trapped in the same dreamscape – on an island colonised by the Lavender Corporation and filled with depressed, abused residents; and the freedom one gets in exploring the city only heightens its claustrophobia and the lack of a way out. (The whole thing was also inspired by American anthropologist David Graeber, author of Debt and Bullshit Jobs, where he argued that the market arises from systemic state violence and modern labour is valorised as virtuous suffering.) At MIT’s List Visual Arts Center, the game will be presented as an installation interspersed with paintings and sculptures of items that appear on Lavender Island – which perhaps more clearly captures the game’s relevance to the world and the environment around us. Yuwen Jiang

Katsuro Yoshida

Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, 13 July–23 September

Saitama native Katsuro Yoshida was a key member of Japan’s Mono-ha movement from 1968 through to the mid-1970s. During this time he became known for his sculptural works composed from wood, sheet iron, stones and paper that echoed the group’s commitment to exploring the properties of materials rather than the technological ‘progress’ that was driving Japan’s rapid industrialisation and modernisation. Yoshida died in 1999, just before Mono-ha and the works its artists produced became fashionable to Western art markets. The rising popularity of this art was partly due to its relevance in the face of late-twentieth-century notions of change in the postinternet, postglobal era, and the promise of a new world to come. Touching Things, Landscapes, and the World (which was presented earlier this year at the Museum of Modern Art, Kamakura & Hayama) offers a broad view of Yoshida’s oeuvre, highlighting his continuous commitment to printmaking (often using the medium to figure out the many ways in which objects are perceived and consumed by humans) and photography, as well as his later embrace of painting and drawing. The latter led to the artist placing greater emphasis on the human body (the 1980s Heat Haze series of paintings combine landscapes with abstracted bodies, while the late-1980s Touch drawings were made from powdered graphite that Yoshida had rubbed onto the canvas with his hands). The exhibition, then, is both a homecoming and a chance to trace the ways in which Mono-ha evolved. Meanwhile, over in Tokyo, there is a chance to see more of Yoshida’s work in a monographic show at Yumiko Chiba Associates. Nirmala Devi

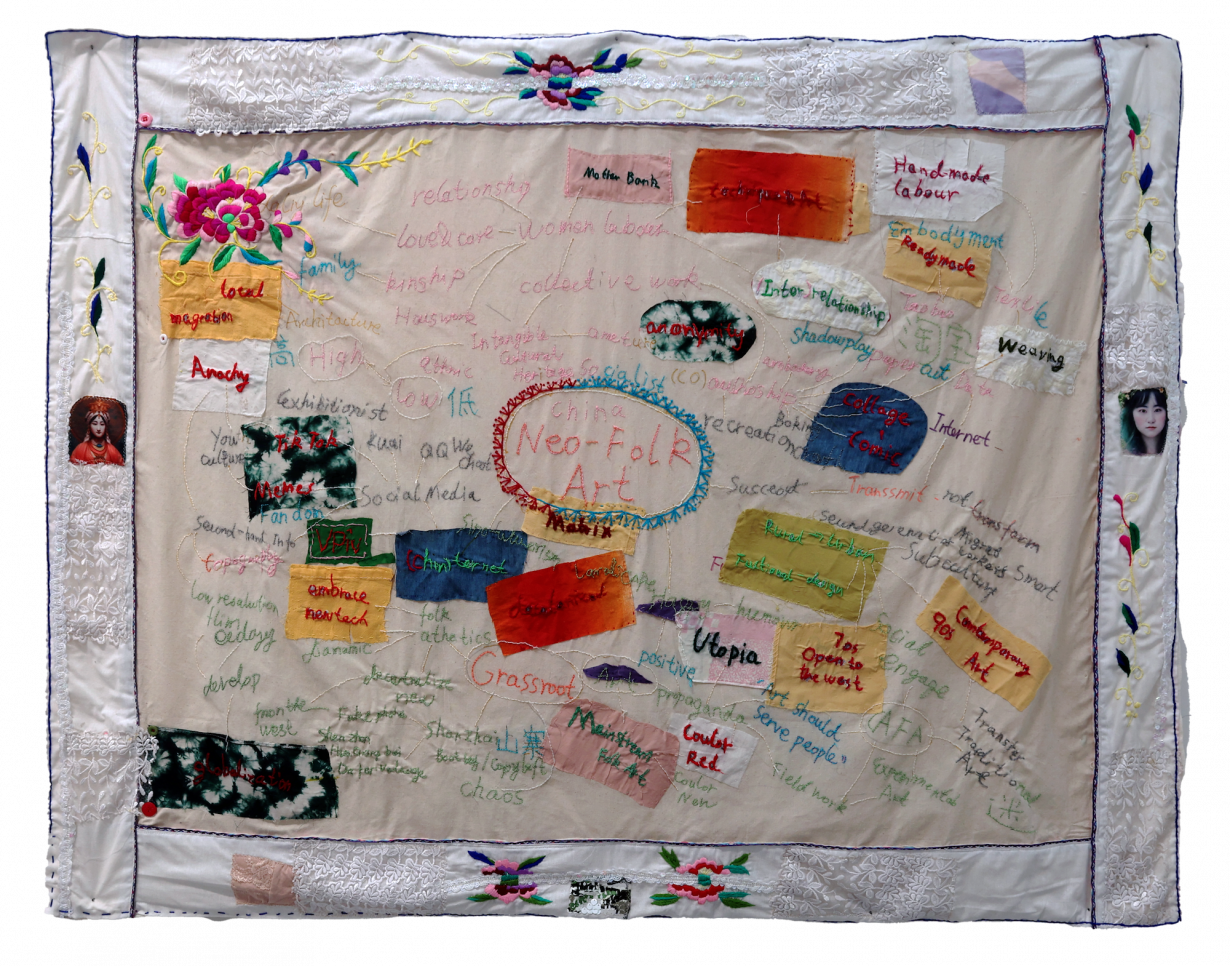

Folk in Order

Macalline Center of Art, Beijing, 20 July–13 October

Folk art often refers to naïve-looking handicrafts made by people untrained, or uninterested, in the world of fine art. To Wang Huan, critic and curator of the Folk in Order, ‘folk’ artistic practice goes beyond stylistic concerns but responds to a mixture of regional heritage, lived experience, common wisdom and alternative knowledge at the margins of hegemonic cultures – which means folk today may now encompass the realm of both popular and subculture. Among the works on view, some represent an interiority: late folk artist Guo Fengyi’s figural diagrams come from her practice of qigong, which to her served as a therapy for her chronic pain and the resulting compositions find a link between what’s felt and what’s seen. Others reflect upon a collective legacy: Minnan artist Chen Huaxian, who studied santan daoist ritual at a Mazu temple in Fujian, gathered found service items to present the material textures of a regional spirituality. Other works here ask us consider ‘folk’ forms and practice in the present tense. Ye Funa’s fabric collage China Neo-folk Art Diagram (2024) is decorated with the garish floral motifs of northern Chinese embroideries, while a hand-sewn mindmap centring on the titular theme brainstorms what ‘folk’ means today, associating the concept with phenomena like TikTok, online shopping and village knock-off culture as well as with key words like ‘utopia’ and ‘anarchy’, which perhaps lurk behind the everlasting ‘folk’ desire to connect to one’s community and stay true to one’s lived reality. Yuwen Jiang

Milo Creese: Day Cry

Daata.art

London-based artist Milo Creese’s videos are full of landscapes that don’t exist, figures that fizzle in and out of reality. Or maybe, given his avowed commitment to working with found footage and stock imagery, Creese’s composited, CGI’d digital hallucinations flow in and out of our millennial, post-truth anxieties about material reality, nature and the digital image’s access to it. In the last year, Creese has launched himself in to working with AI, and this month released three works of a new series, Day Cry. Creese’s three videos, available to screen on digital art platform Daata, revel in AI video’s capacity for disintegration and reality-collapse, but harness this to produce an aesthetic that’s strangely nostalgic – brightly sunlit, full of beaches, blue skies and deserts, bleached and overexposed – while populated by ecstatic, morphing figures. They carry the hallmark slippages of AI vision, in which things oscillate between parallel, not-quite-identical forms. Day Cry (Primer) is full of generic, brightly clothed youth, dancing yet frozen in Arcadian gardens. Day Cry (High Morality) focuses on a naked woman flickering in a vertiginous cloudscape, while in Day Cry (Dirt Farm), cultish, robed figures seem to channel the cactus life vibrating and mutating around them. These euphoric, blissed out visions of dissolution seem like fitting paeans to our end times. Other works by Creese can be seen on the artist’s Vimeo channel. J.J. Charlesworth

」-scaled-1024x768.jpg)