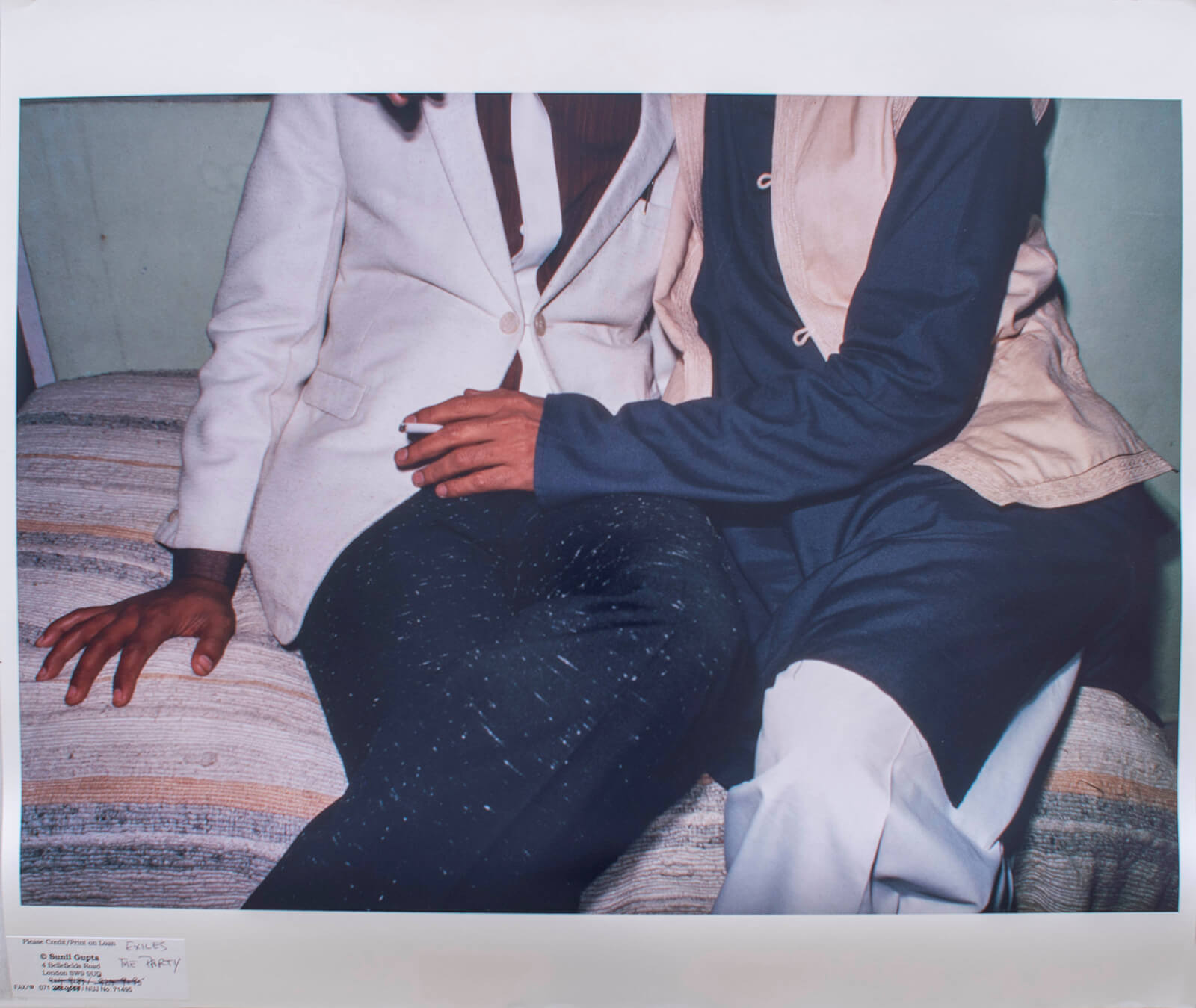

Sunil Gupta is a pathbreaking queer photographer from India who lives in London, the United Kingdom. He is recognised for his landmark 1986-87 photography series Exiles, which documents gay men at Delhi’s monuments. On the occasion of Pride Month 2024, STIR caught up with Gupta for an interview that sheds light on his photography practice and its intersections with Indian politics and the legacy of colonialism. We discussed his participation in the recent group show by Vadehra Art Gallery, People, Places, Things and what the near future holds for the accomplished photographer.

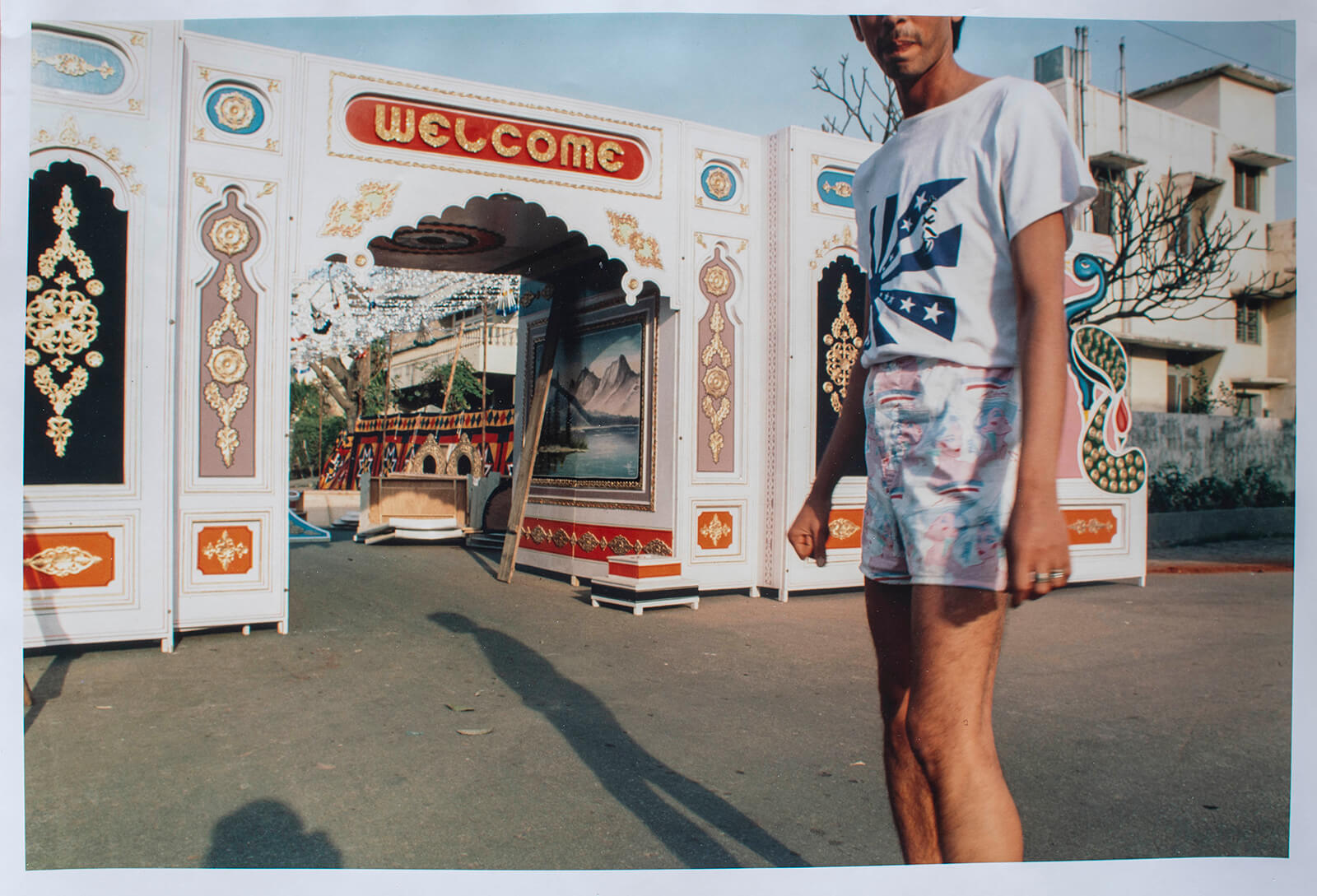

Gupta’s practice has always been closely informed by India’s evolving queer politics. In his early days, including the period when he developed Exiles, Gupta, who was then based in London, realised that gay men in India were quite hesitant to be photographed, as homosexuality was a criminal offence per Indian law. Later, living in Delhi in the early 2000s, he encountered a different socio-political climate, despite the continued existence of the same regressive legislature. He used his camera to seek out answers to the many questions he had about gay culture in India.

The photographer views India’s archaic views on LGBTQIA+ sexuality as a product of the nation’s colonial history. Gupta rightly mentions that colonial laws around sexual identity and behaviour in India and the rest of the British colonies rarely, if ever, took into account Indigenous values. He hopes that his practice as a queer artist and cultural activist has made some contribution to the push for progressive queer legislation in the subcontinent.

Vadehra Art Gallery’s show People, Places, Things brings together works by various artists and photographers, documenting spaces of intimacy. Gupta was initially confused about what he could contribute to the group exhibition, given that there is a great deal of difference between queer and heteronormative spaces of intimacy. Within his own lived experience, there have been few such spaces for queer people.

Those familiar with Gupta’s practice have come to recognise him not only for his bold and uniquely sensitive gaze but also for his rigorous work ethic. The photographer shows no signs of slowing down despite the acclaim he has garnered over the course of his illustrious career and continues to shine a beacon for young queer artists from South Asia.

Edited excerpts from a conversation with STIR:

Manu Sharma: How has India’s evolving queer politics informed your practice?

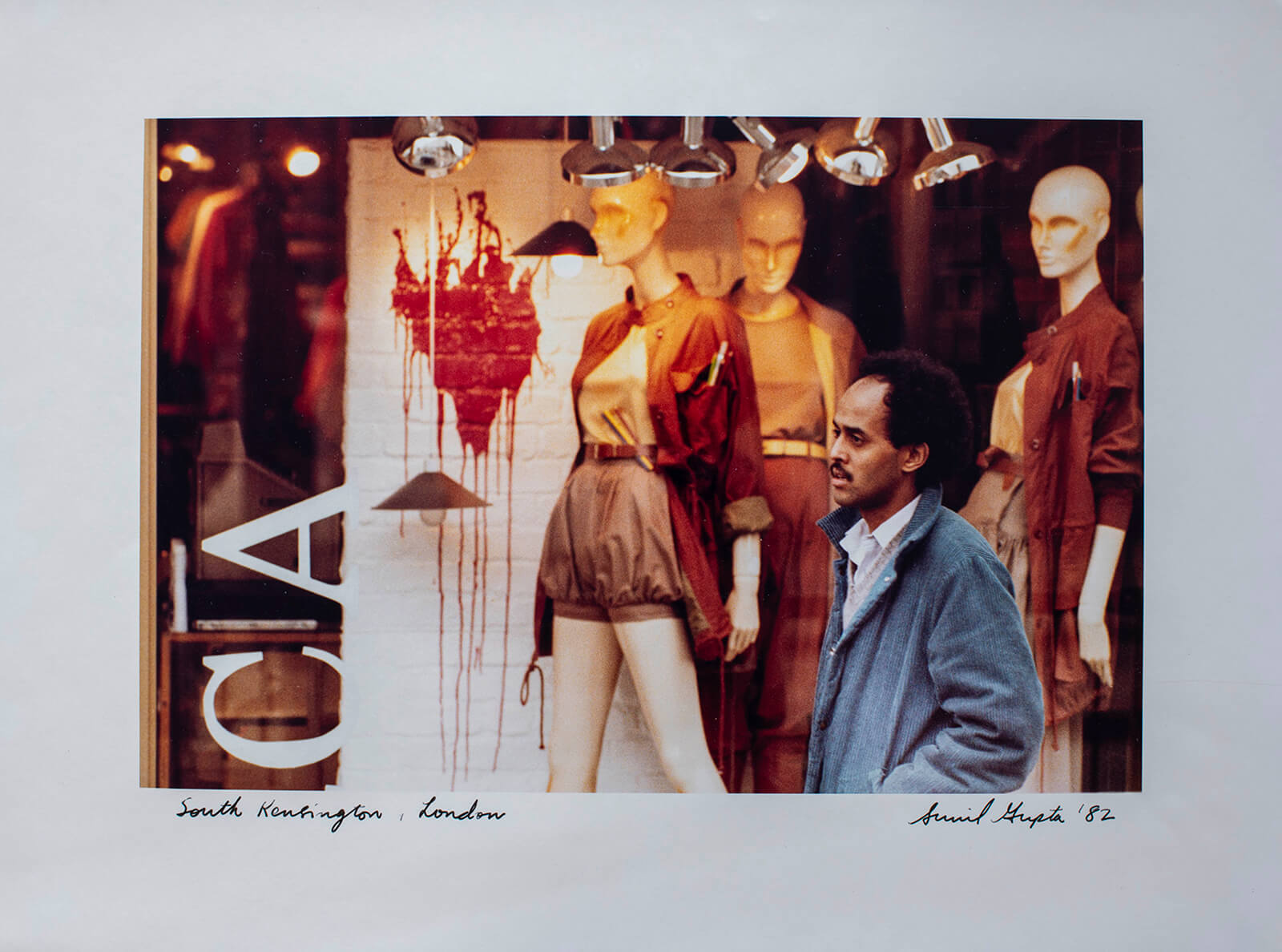

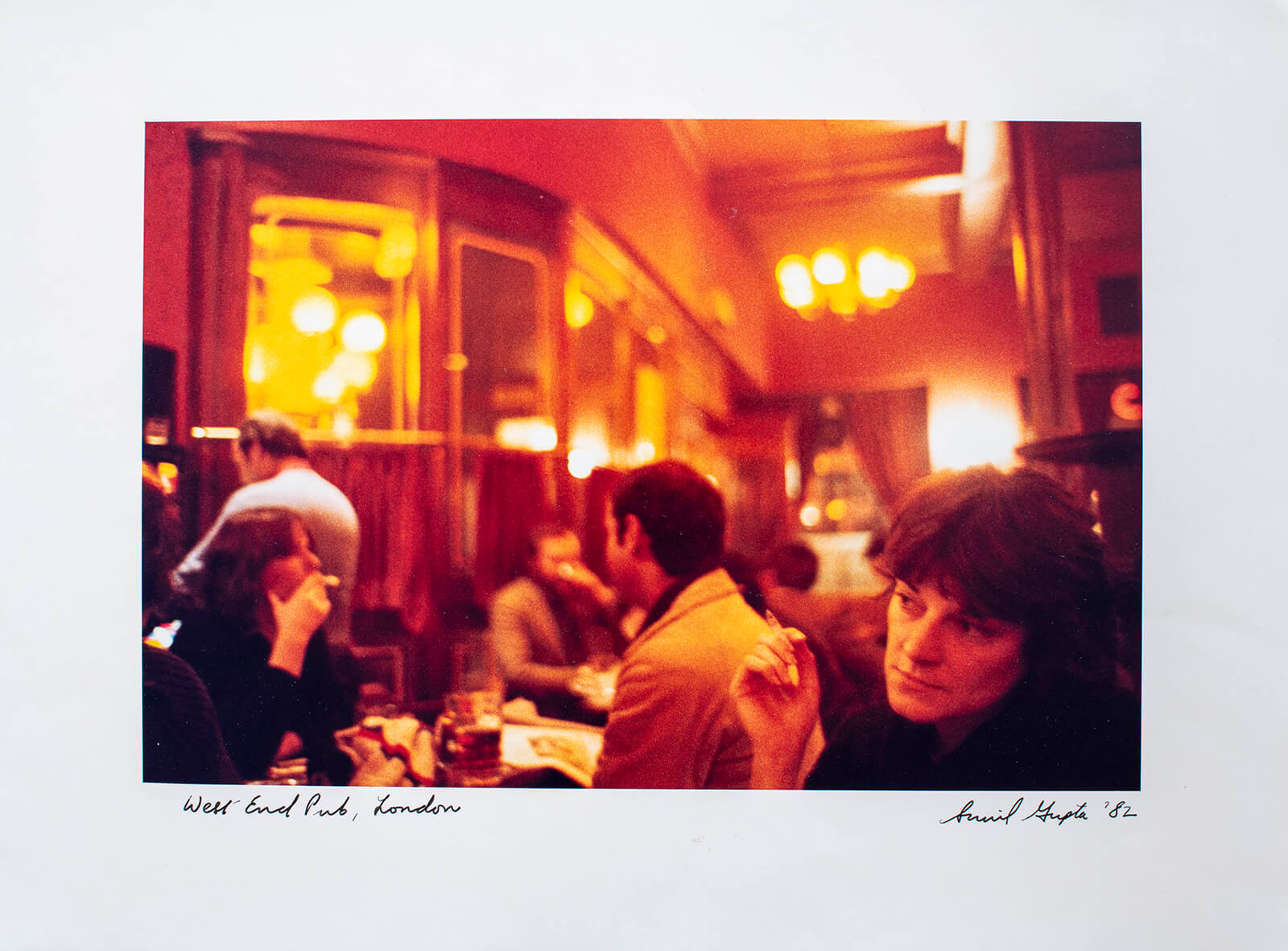

Sunil Gupta: India’s evolving queer politics has informed my practice from the very beginning. When I was an art student way back in the early 1980s at the Royal College of Art in London, I could find no reference to Indian gay men in art history. It became my mission to make work about what it means to be an Indian gay man. [I was] happy making trips back to India, or rather, Delhi in particular, to seek out an answer in pictures, but rather like here in London, gay [men in] Delhi at that time were not willing to be photographed. Much later, when I came to live in Delhi in the early 2000s, I found a very different political climate in which more and more young people were coming out. And they were willing to be photographed. I relocated back to Delhi in order to make a series of different photographic projects and became part of a queer activist group called Nigah, which was part of the larger movement to change the law.

I could find no reference to Indian gay men in art history. It became my mission to make work about what it means to be an Indian gay man.

– Sunil Gupta, photographer

Manu: How does your practice intersect with colonial legacies and decolonialism?

Sunil: Inevitably, as the Victorian habit of categorising everything gave rise to the definitions around sexual deviance and hysterical women, [it] led to defining certain characteristics as “homosexual”, also defining those individuals as criminal. Even the origin of the term “gay” lies within this loosely defined category of immoral women and promiscuous men. The British spread these definitions and this criminalising law to the colonies. In India, this emerged as “Section 377” in the 1850s and a similar section also occurred in a whole range of other British colonies across Asia and Africa. What this didn’t take into account was any Indigenous references or definitions regarding sexual behaviours. It introduced the idea of a criminal sexually defined behaviour to the subcontinent, a legacy which was only finally removed from Indian law books in 2018. I hope my practice as a queer cultural activist made some small contribution to the public debate surrounding this change.

Manu: Coming to People, Places, Things, how does the portraiture of queer and heteronormative spaces of intimacy differ?

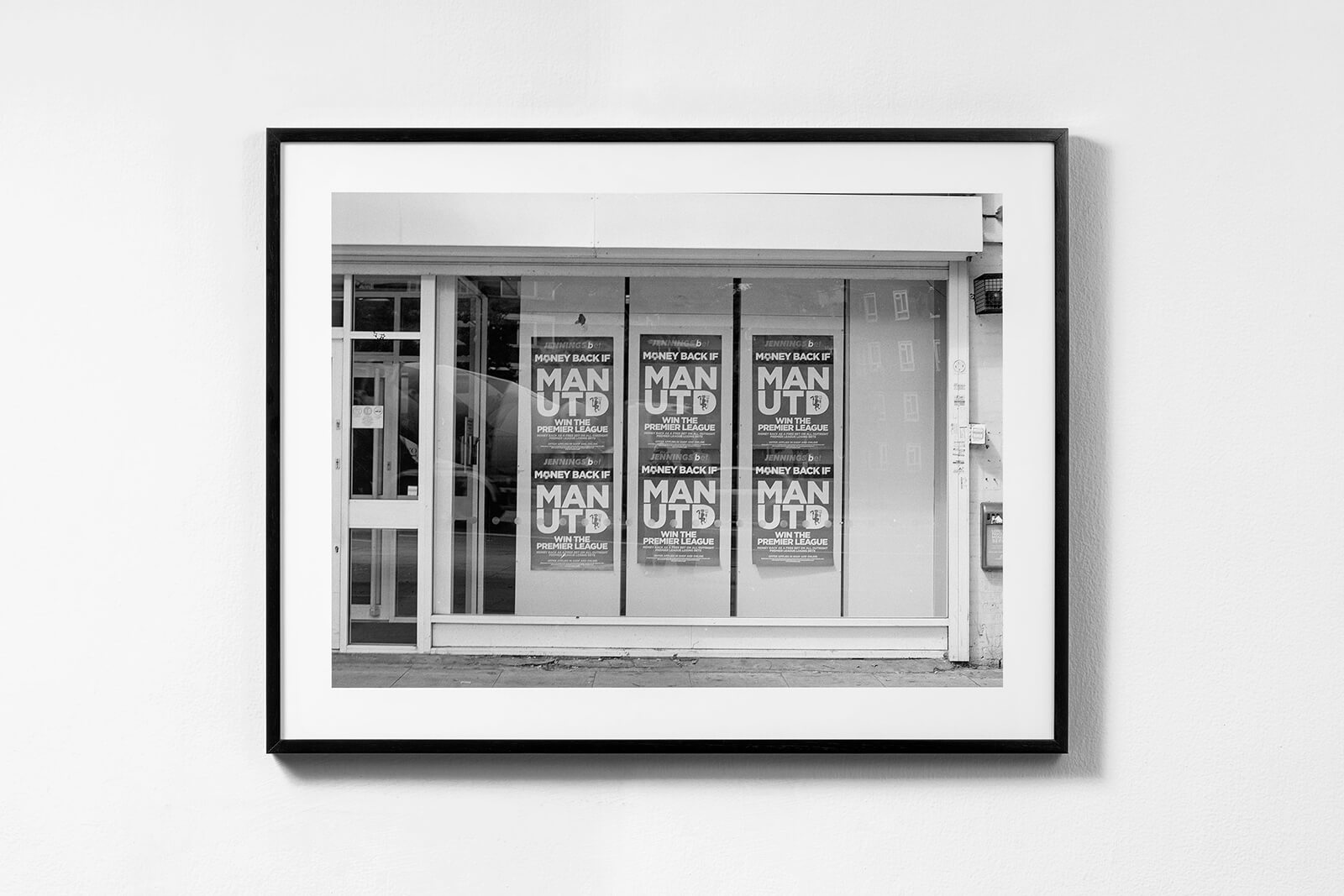

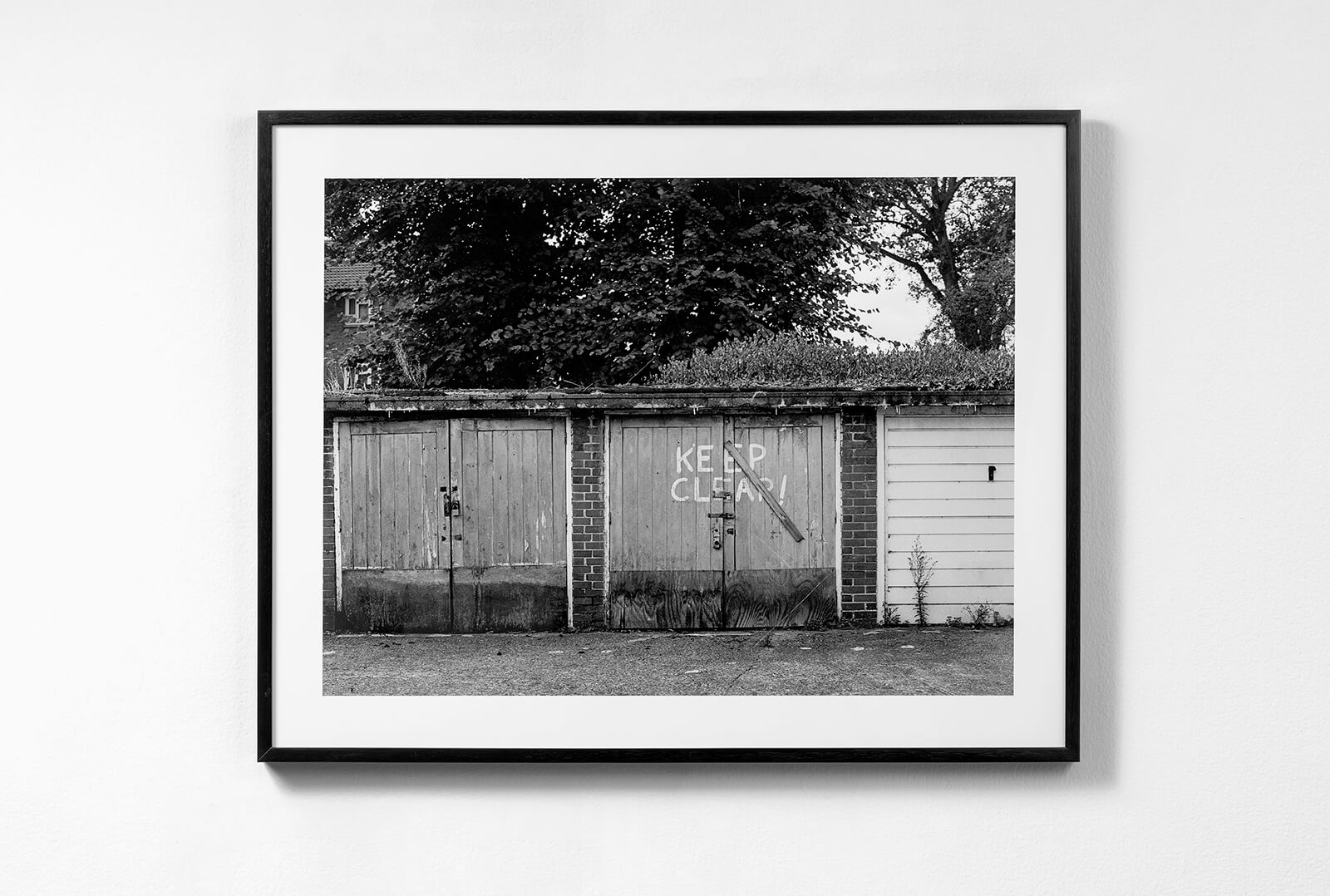

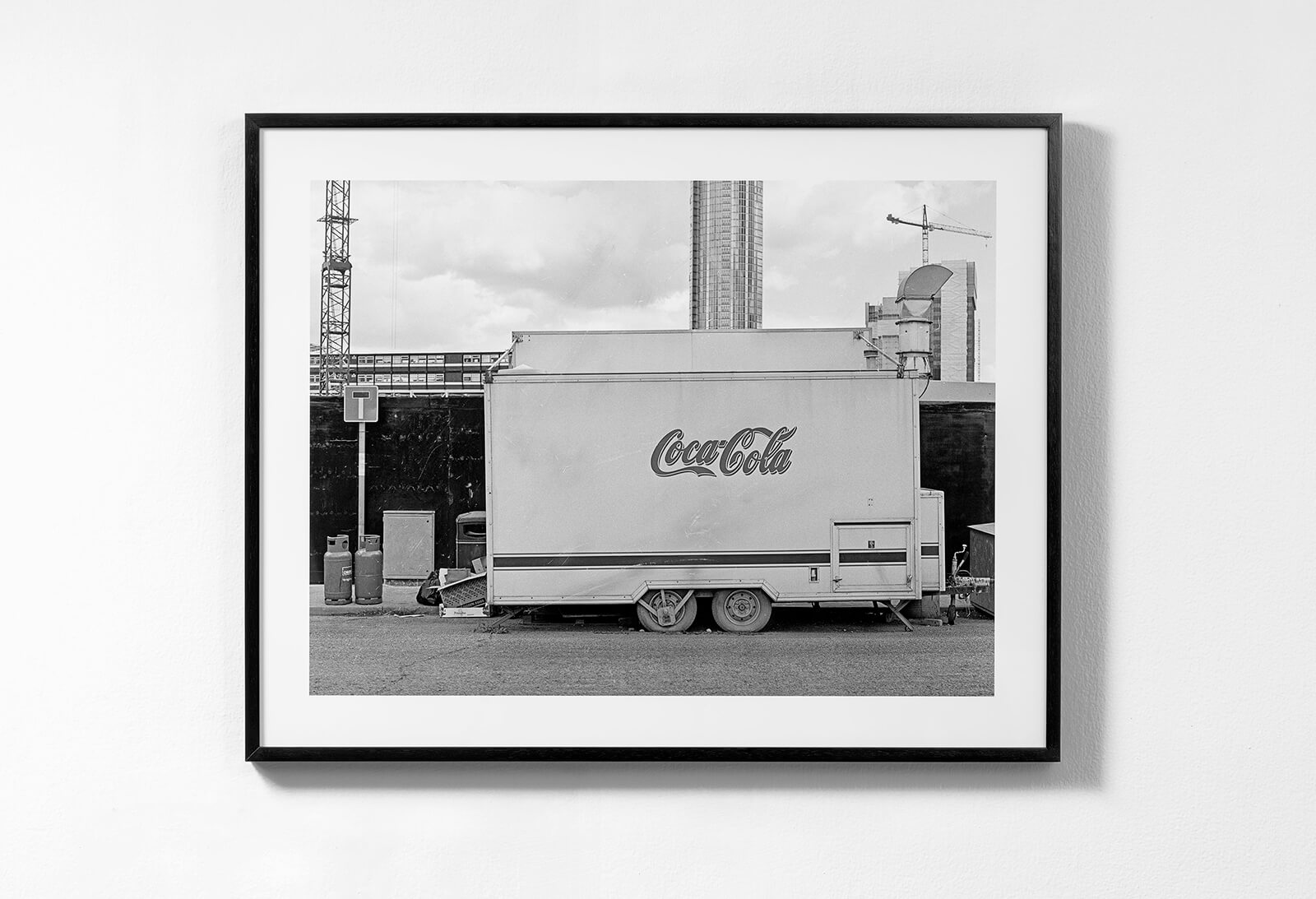

Sunil: The portraiture of queer and heteronormative spaces of intimacy [differs a] great deal, as queer spaces are practically non-existent and usually exist in the public realm. Heteronormativity presupposes private property, marriage and families that would lead to future generations inheriting the bricks and mortar. Pushed out of the family, queers are often forced to exist in liminal spaces. Not only do they have to try and build communities by finding each other, but they also have to negotiate the lack of availability of private spaces. What then to photograph? My contribution to this show was the landscape around my flat in London, in Stockwell, an area that was now occupied by transient communities such as queers and migrants – as the former heterosexual family inhabitants had fled to live in leafy suburbs some years ago.

Manu: What excites you the most about contemporary South Asian queer art?

Sunil: I think the most exciting thing about it is that it is a growing arena. Although [it seems that] there are few opportunities in the subcontinent itself, due to a lack of support from the market and avenues of showing, there are a number of emerging practitioners in Europe and the United States, who are making themselves known.

Manu: Lastly, what is NEXT for you?

Sunil: What is NEXT for me? It’s the publication of another book, I Call You My Love. It is a love story that features the correspondence between a former partner from the late 1980s and I. He was living in New York and getting a PhD at Columbia University and I was in London trying to organise shows and publish books and was part of a movement called Black Arts – of course there will be pictures featured of that time. A second book is also on the way, to be published by the Tate in London. [It is] a small publication in Tate’s series of photography monographs. I am also working on a new photography project called Lovers, Revisited—a collaboration with my husband and partner, Charan Singh. We are updating a 40-year-old project of mine called, Lovers: Ten Years On. This was just launched in our exhibition that opened on June 15, 2024, at The Art House, Wakefield, Yorkshire UK.

As the international LGBTQIA+ community continues to march boldly forward, with greater visibility and advocacy than ever before, it continues to make original art that tells important stories. And we at STIR are always listening, eager to bring you more voices in the years ahead. Happy Pride Month!