The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is all too often associated with violent conflict, at the expense of its positive aspects. Reports on this huge country, the second largest in Africa after Algeria, and nearly twice the size of South Africa, tend to overlook its intellectual and artistic vibrancy.

My research has focused on this part of the continent. This article is based on two recent contributions in which I examine the DRC’s cultural richness and explore the role and place of mineral extraction in its literature and art.

The contribution of the DRC to Africa’s culture is immense. In precolonial times, Congolese sculpture and textiles counted among the continent’s most remarkable cultural achievements. During colonial occupation under the Belgians (1885-1960), major painters Djilatendo and Albert Lubaki and writers (Paul Lomami-Tshibamba) emerged. After decolonisation (1960), the Congolese rumba became one of the most performed musical genres in Africa.

From 1990 to 2006, however, this cultural effervescence came to a halt.

The two main factors were the political violence that accompanied the end of Mobutu Sese Seko’s dictatorship (1965-1997), and the consequences of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. The genocide precipitated a murderous conflict usually referred to as the “Congo Wars”.

Following the first democratic elections in 2006, cultural activities gradually resumed. The DRC experienced a surge of creativity in all areas.

This revival is visible in the work of Sammy Baloji (born 1978), a photographer, filmmaker, installation artist and curator from Lubumbashi, Katanga. I believe he is key to understanding Congolese culture in the last two decades and the proliferation, across literature and the arts, of environmentally conscious works. His production allows us to revisit Congo’s past and understand the role Congolese artists have played in decolonisation.

The artist at work

Baloji has become a major cultural promoter in the DRC and the Congolese diaspora. He has inspired and worked with a diverse group of figures. Achille Mbembe, the political theorist and historian of decolonisation; Fiston Mwanza Mujila, the author of Tram 83; Filip De Boeck, the social anthropologist; and Bambi Ceuppens, the art historian, are among them.

In his multi-media production, Baloji recycles colonial archives and artefacts. This, as a means to understand the roots of (neo)colonial extraction of the DRC’s minerals and initiate new debates on the many human and environmental abuses this process has generated.

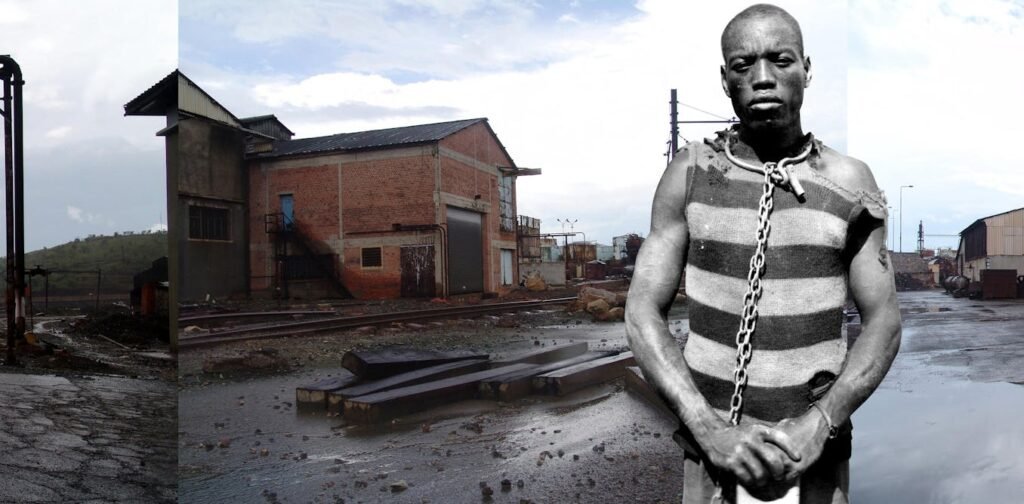

Baloji came to prominence with Mémoire (2006), a series of photographs and collages.

Sammy Baloji

In these artworks, he skilfully mixes his own photographs with colonial archives. By superimposing pictures of early 20th century African miners employed by the then all-powerful Belgian Union Minière du Haut Katanga over images of devastated 21st century mining sites, Baloji shows the enduring significance of mineral extraction for his native country.

He uses mining to reflect on the paradoxes behind the DRC’s rich subsoil.

At the end of the 19th century, the rubber from Congolese forests enabled the automobile industry to develop. Since the 2000s, Congolese coltan and cobalt have been instrumental in manufacturing mobile phones, computers and electric batteries.

The world’s planetary mobility – on roads and digital superhighways – has depended on the DRC’s resources.

Baloji uses film and photography to show that despite its minerals, the DRC has remained an extremely poor country. While remembering the past and past abuse, he also explores and praises the resourcefulness of local people.

In Mémoire/Kolwezi (2014), his photographic portraits of young artisan miners do not shy away from the extreme danger of their activities.

Sammy Baloji

However, Baloji refuses to present them as victims. The miners dream up – in fact, Photoshop – idealised images in which Congolese mining pits cohabit with alpine fields and high-tech Chinese megacities.

Baloji does not say these images, which adorn the artisan miners’ homes and are incorporated into his own photomontages, make the miners immune to the violence of globalisation. But he contends that they attest to dreams and hopes for a better future.

Challenging the biased colonial view

Baloji has reflected on how photography, as an artistic and documentary tool, has contributed to the understanding and misconstruing of Africa.

His approach establishes a bridge between art and research, as I have shown in my articles. It is based on the premise that, until the end of the colonial era, knowledge of the Congo was mostly mediated by westerners.

His collages and installations, which combine past and present images and objects, challenge the biased colonial setting of these early representations. He pursued this objective in the recent exhibition at Tate Modern in London, A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography.

Baloji’s early work was exhibited alongside other pieces by environmentally committed Congolese photographers such as Kiripi Katembo and Léonard Pongo.

His vast and multifaceted production has been shown in Dakar, Lyon, Venice, Bamako, Luanda, Ouidah and Zurich. Baloji has been keen to collaborate with former colonial museums.

In 2011, Baloji and Maarten Couttenier, a Tervuren-based historian, revisited the Katangese locations where Charles Lemaire, the Belgian army officer, had conducted his reconnaissance mission (1898-1900) to collect artefacts and gather scientific data.

Baloji showed the photographs and paintings produced during this notorious expedition to the descendants of those who had been humiliated, robbed, displaced, maimed and assassinated by the Lemaire personnel.

His aim was to gather a new body of evidence of how this traumatic event had been remembered by Katangese. It also enabled him to question colonial archiving methods by creating photographic diptychs – images made in two parts, often attached by a hinge – in which the late 19th century representations of Katanga are combined with his own material.

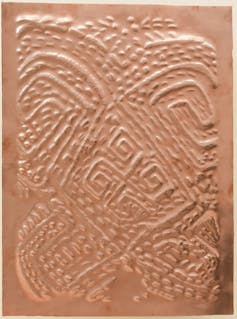

This focus on colonial traces has led Baloji to engage in abstract experiments. These are exemplified by Sociétés Secrètes (2015), a series of copper bas-reliefs engraved with ritualistic scarification.

Sammy Baloji

Although beautiful objects in their own right, these artworks also point to more hidden meanings. The use of copper revisits the large-scale extraction process initiated under Belgian colonialism. Ethnic scarification was photographed by colonial officials to classify and police local people.

In Baloji’s works, past and present are overlaid. Not just because the past keeps repeating itself, but because this confrontation offers a fresh look at so-called historical truths.