So what about the other guy?

Well, do you know the name Todd Webb? Because if you don’t, that’s also how it ends.

In 1955, Webb was a highly regarded figure in American photography. A protégé of Edward Steichen and a friend of Dorothea Lange, he was part of an inner circle of favored photographers, a fixture in some of the most important exhibitions of the era.

But after selling off his archive to a dealer who kept his work out of circulation, Webb fell into obscurity. During the 1970s and ’80s when curators and tastemakers were establishing the canon of 20th-century photography, he was barely considered. So while Frank’s “The Americans” is everywhere, Webb’s photographs from his 1955 travels have never previously been exhibited.

A superb exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Mass., corrects this. Organized by Lisa Volpe, the show opened late last year at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and will travel to the Brandywine Museum of Art in Pennsylvania in February.

For Webb’s reputation, it has to be said that “Robert Frank and Todd Webb: Across America, 1955” is not ideal. Just as it isn’t fair to Antonio Salieri always to be putting him on concert programs with Mozart, it’s not quite fair to Webb to put his 1955 project alongside Frank’s. He can only suffer by comparison.

Still, fairness be damned. As a sense-sharpening exercise, it’s irresistible, and highly instructive. Something about it recalls the mechanics of the scientific method.

You start with a question — let’s say, about America (“What sort of place is it?”) or aesthetics (“Can photographs rise to the level of the greatest art?”). You conduct a little research and concoct a hypothesis, e.g., “America is sad” or “Photographs are documentary, not artistic.” For a good experiment, you need a control. So: Two photographers. One gets the drug, the other a placebo.

A cursory analysis of the results leaves little doubt: Frank got the drug. And whatever it was, its efficacy cannot be questioned.

But the beauty of this exhibition is that it invites us to take another look, and to entertain less binary conclusions. It will make you see America and photography with freshly rinsed eyes.

The two photographers had similar kinds of curiosity but very different ways of seeing. Both were more attracted to people than to landscapes or things. They photographed roads and roadside businesses, billboards and signs, bars, parades, rallies, and public transport. They were alive to big themes like class and race relations, but also to the accidental, strangely poetic shapes made by bodies lying on picnic rugs or getting off chairlifts.

Frank, who traveled the country in a used 1950 Ford Business Coupe, whittled down the 83 photographs that made it into “The Americans” from 28,000. He was in his early 30s.

Webb, who traveled by foot, by raft and by bike, made his selections from a total of 10,000. So it’s fair to say that Webb took more trouble with his photographs. They are more calculated and deliberate. They’re also more static.

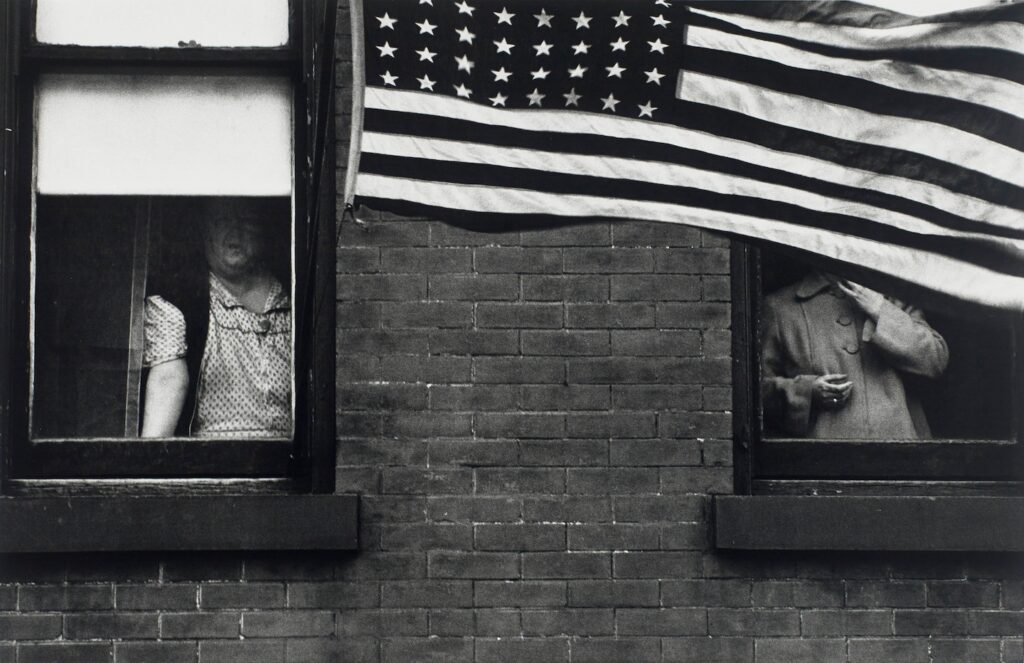

Frank’s photographs, by contrast, are mobile and responsive. “The places that interest me are on the way,” he said. There’s something clandestine and erotic about them, like a rueful exchange of looks between thwarted lovers across a loud restaurant table. Tilted and cropped, his pictures twitch with an animal alertness. Many envelop pockets of poignant focus in seas of blur, so that they feel targeted, ardent, but snatched on the run.

As indeed they often were. Frank showed silver-shining strips of road stretching miles ahead. The car itself was often his tripod. In the mid-1950s, many of the roads he traveled on were new. They made new parts of the country available to Frank’s camera. And they generated new kinds of phenomena: roadside diners, signs, billboards, gas stations.

Frank would place his camera low for some subjects, so that they loomed overhead like mysterious adults dimly perceived from a child’s cot. Alternatively, he’d photograph from an elevated vantage point: The resulting picture would express levels of power, degrees of separation, atomic loneliness.

In 1955, Webb was 49 years old. Like Frank, he had a natural sympathy for people who were marginalized, overlooked, factored out. His decision to avoid car travel was obviously consequential, but he didn’t want walking and cycling to become the point of the exercise. “The trip itself as it stretches out assumes the dimensions of a saga,” he wrote to his wife, Lucille. “There was one stretch between Lovelock and Fernley — 40 miles without a tree or blade of grass and an inferno of heat.”

His portraits pulse with human sympathy. But they’re also relatively conventional — the result of calculated, very intentional encounters. Compare them to Frank’s photographs of people, and you realize you are dealing with two different ideas of portraiture. Frank’s was intrinsically photographic. It was rooted, that’s to say, in a deeper feeling for the ramifications of the camera’s intrusiveness. “Once someone is aware of the camera, it becomes a different picture,” he said. He chose not to suppress or sidestep this fact, but to make hay with it.

His own favorite photo from “The Americans” was taken in a sloping park in San Francisco. “I was sitting down — sitting on the grass — behind these people, then [the man] looked back. It’s the look you often get as a photographer when you intrude.” (You understand something about intimacy when you break it.)

A lot of the sadness that comes off both bodies of work can be read as the sadness of what Volpe, in the show’s excellent catalogue, calls “the forms of destruction, injustice, and rabid consumption perpetuated in the name of American freedom.”

But then again, it’s also just human sadness. And sometimes it’s not even sadness: It’s solitude, absorption, oblivion. “The world moves very rapidly and not necessarily in perfect images,” said Frank. This is not a sad statement in itself, just a true one.

If Frank was responding intuitively to the world around him, he was also reacting against the artifice he detected in earlier styles of photography. Instead of determinedly hunting for life’s “decisive moments,” in the manner of Henri Cartier-Bresson, he seemed more curious about the moments before and after. His vision was almost syncopated in this sense. It was also achingly unresolved, like life. There was no clear beginning, no pivotal transformation, no resplendent culmination. Just degrees of shuffling along, each moment potentially momentous — or not.

In 1955, Frank was also shuffling along, albeit at high speed, sometimes with his wife and young children in tow, sometimes solo. “It seems nothing is really behind you,” he said, “girls you have known, or your children, or the town you came from. It’s all still with you in some way.”

“The Americans,” which I first discovered as a teenager, will always be with me in some way. Webb, meanwhile, is a welcome new discovery. He may suffer by comparison with Frank, but not too badly. He took more than enough wonderful photographs to earn our admiration (not least “Diner, Ouray, CO”). His 1955 project, uncovered at last, deserves to be examined on its own terms. But I see nothing wrong with acknowledging that studying Webb also serves to sharpen our appreciation of Frank.