“Peter got exactly what he wanted,” a friend of Peter Hujar’s told a writer more than a decade ago. Speaking to Cynthia Carr for her biography of David Wojnarowicz, Steve Turtell continued: “He once said to me, ‘I want to be discussed in hushed tones. When people talk about me, I want them to be whispering.’”

In case you haven’t noticed, nobody is merely whispering Hujar’s name these days. To say that the legendary New York photographer, who died in 1987 at the age of 53 from AIDS-related complications, is enjoying—or, sadly, not enjoying—a renaissance is an understatement. And though his pictures seem to be everywhere, from the cover of an Anohni and the Johnsons album to Hanya Yanagihara’s bestselling novel A Little Life, they still maintain their edge.

Over the past decade, Hujar, best known for his astutely composed black-and-white studio portraits of friends, lovers, artists, intellectuals, and queer icons from New York’s underground, has crossed over into the mainstream in ways that were once unimaginable. He had only a handful of solo exhibitions during his lifetime, but since 2017, when the Morgan Library in New York and Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid organized the richly researched traveling show, “Peter Hujar: Speed of Life,” numerous institutions have been acquiring his photographs and collaborating with his estate to develop curatorial projects that further cement his place within the histories of art and photography. Even Elton John, an avid Hujar collector, has played a role: he curated a survey of Hujar’s work in 2022 at Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco, and several Hujar prints feature in “Fragile Beauty: Photographs from the Sir Elton John and David Furnish Collection,” now at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

And two other notable Hujar solo shows have recently gone on view: “Portraits in Life and Death” at the Istituto Santa Maria della Pietà in Venice (a collateral project of the Biennale) and “Rialto” at the Ukrainian Museum in New York (which closed in September). The Hujar Estate just republished Portraits in Life and Death, his hard-to-find 1976 book featuring 41 photographs of the Catacombe dei Cappuccini in Palermo, Italy, and his avant-garde contemporaries in New York. The reissue contains a new preface by Benjamin Moser, the biographer of Susan Sontag, one of Hujar’s dear friends, who wrote the introduction to the first edition, and also appears in an iconic picture therein, recumbent with upraised arms folded to cradle her head.

Peter Hujar: Young Self-Portrait (IV), 1958.

©The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beyond all that, the recent attention Hujar has drawn rises above the realm of exhibitions and photobooks. He is increasingly becoming a figure of pop art history, a fascinating case study in photographic subjectivity and identity from an era when the New York photography, art, and queer worlds had forged fraught yet flirtatious relationships. Any photographer working in self-portraiture, as Hujar did, in the most pensive of poses, is prone to exaggerated mythological construction. (See Claude Cahun, whose self-portraits transgressed the gender binary in the early 20th century, or Robert Mapplethorpe, Hujar’s younger and more famous contemporary, who daringly photographed himself in BDSM accoutrements.) In certain ways, Hujar’s depressive, curmudgeonly, captivating, sometimes goofy sensibility perfects that age-old artistic archetype of the tortured genius burrowed deep in our cultural imaginary.

One recent contribution to the mythologizing phenomenon is Peter Hujar’s Day (2021), a singular book by Linda Rosenkrantz. In Warholian fashion, Rosenkrantz asked Hujar, who had then been one of her closest friends for almost two decades, to jot down the totality of his activities on the arbitrary date of December 18, 1974. The following day, she recorded him recounting his undertakings. Published in book form for the first time in 2021 after the work’s rediscovery, their unedited transcribed conversation has Hujar drifting through the mundane and the wonderful with meticulous detail: photographing Allen Ginsberg for the New York Times, hanging out with disco writer and later photography critic Vince Aletti (who comes over to use the shower), and eating takeout moo goo gai pan and sweet and sour pork.

At one point in this meandering dialogue, Hujar brings up some of his ambitions for Portraits in Life and Death, then in the works: “I really would love to make money off of it. And also to have it get around. You know I’ve always had a star thing, wanting to be some kind of a star or a star.” Probably uttered with irony, given his lifelong entrepreneurial shortcomings and reluctance to professionalize, these comments have taken on new and more resonant meaning since an announcement this past January that Peter Hujar’s Day is the subject of a forthcoming feature film by the acclaimed arthouse director Ira Sachs. Hujar will be played by Ben Whishaw, who also starred in Sachs’s 2023 hit Passages, one of many Sachs films about unbearable yet nonetheless lovable gay artists. One wonders too if Hujar will figure in the storyline of Zackary Drucker’s biopic about Candy Darling, the Warhol superstar whom Hujar monumentalized in a transcendent pose on her deathbed.

Peter Hujar: Candy Darling on Her Deathbed, 1975.

©The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While neither Nicole Kidman’s performance as Diane Arbus (in Fur: An Imaginary Portrait of Diane Arbus from 2006) nor Matt Smith’s as Robert Mapplethorpe (in Mapplethorpe, 2018) was memorable enough to redirect with the long-standing cultural perceptions of those photographers, it’s likely that, in Sachs’s hands, Hujar’s Hollywoodification will have a transformative effect on the future reception of his life and work. With that, there will be even less whispering and even greater potential that Hujar’s storied (self-)construction in photography, writing, and film will overshadow the subtlety of his work as it gets championed with more and more passion.

AS WAS THE CASE for many of my generation (born in 1990 and raised in the United States), Hujar crept into my consciousness through his friendship with and mentorship of David Wojnarowicz, a multimedia artist and AIDS activist who experienced a fiery resurgence in academia, the art world, and even popular culture in the 2010s. Wojnarowicz, who had a history of being targeted in the Culture Wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s, has been in the spotlight several times since, despite having died of AIDS-related causes in 1992.

In 2010 conservative homophobic activism prompted the removal of an edit of his unfinished 1987 film A Fire in My Belly from the exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture”at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. After that came Carr’s stupendous biography Fire in the Belly in 2012, a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2018, and a steady stream of scholarly projects. It felt like a new era of American queer art history, one that coincided with a capacious and critical revisitation of cultural practitioners who died during the early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis as well as those whose work seemed to forecast or foretell the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Peter Hujar: Self-Portrait Lying Down, 1975.

©The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Concurrent with this renewed interest in Wojnarowicz and his milieu, there’s been a strong interest in resurfacing and generating new historical accounts of New York’s queer photographic communities in the glowing period of the roughly 15 years between the Stonewall riots and the AIDS pandemic’s radical reshaping of queer life. Often positioned as a father figure of queer photography, Hujar belonged to a network of cultural producers that certainly, as the celebrated subjects in his pictures evidence, predated his relationship with Wojnarowicz. From 1968 to 1971, Hujar collaborated with Steve Lawrence and Andrew Ullrick to publish Newspaper, a wordless, pictures-only periodical that in 14 issues showcased the work of several queer artists in their circles. Last year, Primary Information, a publisher of out-of-print artist books, released a collated version of all the editions of Newspaper, introducing this inventive and overlooked project to a new generation.

Numerous other practitioners formed an amorphous gay photo world of the 1970s and early 1980s that built on the work of Arbus, Richard Avedon, Lisette Model, and Warhol. While many were outliers rather than core participants, this coterie included Mapplethorpe, Duane Michals, Arthur Tress, Stanley Stellar, Christopher Makos, Lucas Samaras, Bruce Cratsley, Robert Giard, Alvin Baltrop, Tseng Kwong Chi, Gary Schneider, Allen Frame, Nan Goldin, and Darrel Ellis. Most of these artists knew Hujar; some were mentored by him, and some despised him. Hujar and his rival Mapplethorpe were a study in contrasts: the former’s refusal to ingratiate himself with the art world vs. the latter’s celebrity status due to years of strategic self-marketing, the former’s quest for complexity vs. the latter’s obsession with beauty, the former’s discernible compassion toward his models vs. the latter’s sometimes clinical disconnection.

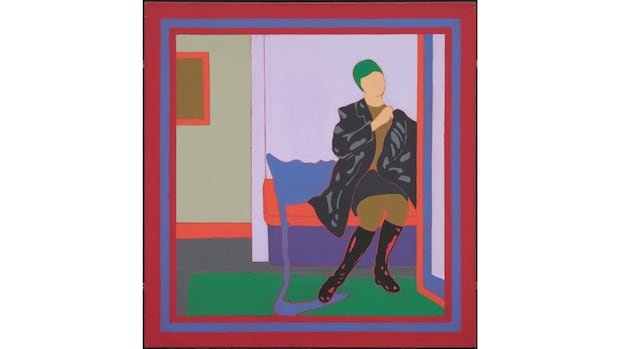

Peter Hujar: Divine, 1975.

©The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Recent books and exhibitions have brought new attention to Ellis, a Black artist who figures in otherwise predominantly white histories. In 1981 Ellis, then an emerging artist whose experimental work blended photography with painting, modeled for Hujar. The portrait, at once regal and vulnerable, shows Ellis gazing upward with a vacant countenance as his head rests on what is perhaps the arm of a couch. Seven years later, Ellis, who had also posed for Mapplethorpe, reinterpreted the two photographers’ portraits by reclaiming them as more expressive painted self-portraits. “I struggle to resist the frozen images of myself taken by Robert Mapplethorpe and Peter Hujar,” he wrote as a caption in the exhibition catalog for “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing,” an AIDS activist show at the Artists Space in New York in 1989. “They haunt me.” Besides underscoring the racial politics at play in Hujar’s original photograph—something that tends to be left out of discussions of his work, since most of Hujar’s subjects were white—Ellis’s work might be viewed as an act of commemorating the recently deceased artist whose AIDS-related death foreshadowed Ellis’s own.

Hujar’s enduring influence can also be felt among contemporary artists, as many diverse practitioners—among them Every Ocean Hughes, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Elle Pérez, Patrice Helmar, and Matthew Leifheit—cite his work as inspiration. In 2021, after immersing herself in Hujar’s archive, Moyra Davey even published an artist book that staged a visual conversation between their distinct practices, a poetic and genealogical act of appreciation. Wearing the hats of both artist and curator, Davey mixes her images together with Hujar’s such that the reader cannot differentiate their authorship without the book’s index.

WHILE IN VENICE over the summer to see Hujar’s latest exhibition,one of the most significant collateral events around the Biennale, I breezed through Mary McCarthy’s pithy book Venice Observed (1956). “One gives up the struggle and submits to a classic experience,” McCarthy writes about the challenge of theorizing the floating city. “One accepts the fact that what one is about to feel or say has not only been said before by Goethe or Musset but is on the tip of the tongue of the tourist from Iowa who is alighting in the Piazzetta with his wife in her furpiece and jewelled pin.”

Reading this passage, I was struck by how Hujar’s life and work might prompt the same sort of platitudes, given the cottage industry of critics, scholars, curators, and artists waxing lyrical about the raw intimacies between Hujar and his models, the fineness of his printing, or his difficult persona. But even as we may think we know the man and the images, there’s always more to consider.

Peter Hujar: Palermo Catacombs #1, 1963.

©The Peter Hujar Archive/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Admirers of Hujar’s photographs are well rewarded to contemplate his work in relation to the specificity of place. As in the book that informed the exhibition, “Portraits in Life and Death” in Venice brings together two bodies of work: a group of New York portraits taken in 1974 and 1975, mainly of figures like the critic Fran Lebowitz and the drag queen Divine, and stirring pictures of mummified corpses in the Catacombe dei Cappuccini, which Hujar visited in 1963. While the juxtaposition of the living and the dead did not please everyone when he configured his book back in the 1970s, Hujar gave the mummies the same painstaking attention he gave his contemporary subjects, many of whom were lying down or in states of repose.

In her indelible introduction to the book, Sontag wrote “photography converts the whole world into a cemetery.” That might be an overstatement, but it aptly evokes elements of Hujar’s artistic vision and the quality of haunting that accompanies our engagement with his life and work as he continues to ascend in the art world and across the cultural domain. Even as Hujar moves into the limelight of art history, what continues to keep his work vital and endlessly affecting is the undeniable entanglement of life and death.