As a child growing up in the Hare Krishna community in the United States, I was forbidden to be outside during a solar eclipse.

In our version of Vedic astronomy, eclipses are believed to be a deeply inauspicious time when the demon Rahu’s decapitated head chases the sun and the moon. In this chase, Rahu’s head obscures or swallows the sun. A visceral fear would sweep our community as an eclipse approached. We crowded into the inner sanctum of the temple to recite prayers, hoping to counteract the forces of darkness that were consuming our universe. As totality enveloped us, a profound sense of unity between our community and Lord Krishna crescendoed. As Rahu receded, the sun gradually dispelled the darkness, bringing collective relief as the forces of goodness triumphed over chaos once more.

Many ideas in Vedic cosmology (which seeks explanations for both human and nonhuman affairs throughout the universe) depict the physical universe as profoundly animate and vibrant. Some explanations for the mechanics of the observable world mirror modern understandings of concepts like the atom, the cyclic nature of time at scale and quantum mechanics’ “many worlds” theory. But it is still an ancient set of beliefs where planets possess their own personalities, akin to living deities or demons. I am no longer religious, and do not believe in god nor superstition. But growing up, I regarded existence as a grand stage where conflicting energies of chaos and order perpetually and cyclically clash, each vying for supremacy before gradually reconciling and reaching a delicate equilibrium where they coexist in a harmonious, unified balance.

Observing the sky and fully embracing the belief that an eclipse occurred owing to a demon’s attempt to devour the moon or sun shaped my early worldview. But over the years, my exposure to scientific readings — especially “The Demon-Haunted World” by Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan, which sought to explain the scientific method to the general public — gradually transformed those views. I shifted away from a mythic-religious perspective and embraced modern science, and learned that a solar eclipse is the moon passing between the earth and the sun, obscuring our view of the sun.

This transition didn’t diminish my sense of awe and wonder toward the cosmos. If anything, it only heightened my appreciation for the complexity of the universe, my curiosity to learn more and my desire to translate these cosmic mysteries through my artistic practice. Celestial bodies aligning with each other now seems like a more miraculous event than a demon head flying through space.

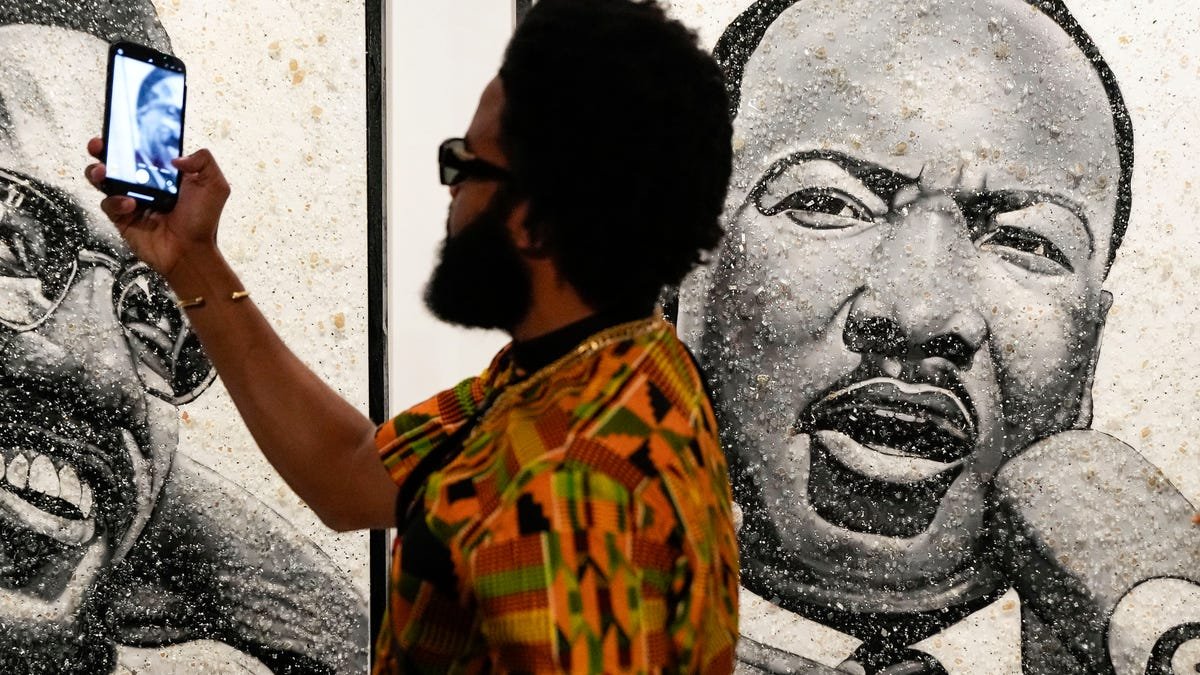

Ontological questions have always been at the root of my artistic practice. My work is an attempt to tap into the mythologies we’ve inherited from our ancestors through cave paintings, religious texts and other materials — and reinterpret them into a modern context that pays homage to these ancestors while creating a new vocabulary of archetypes that are relevant to our era. I believe these archetypes can represent the outer limits of our rational understanding, and live side by side with the gods of old mythologies.

I am grateful for the upbringing that immersed me in a mythological worldview at a young age. I now have a bridge of understanding not only to our ancestors but also to billions of living people who hold beliefs that cannot always be explained by science. As the drama of the cosmos plays out in our tiny and insignificant corner of the universe, events in the sky like solar eclipses are now our mirrors, reflecting our projections and beliefs.

The total solar eclipse, with masses of humanity witnessing it, is the closest most of us will get to the overview effect — the rare experience astronauts have when they are in space and look back to see the Earth, and feel an overwhelming sense of universal connectedness. The experience of solar eclipse totality is often described in a similar way: a brief glimpse into an altered state where for a few moments, everything under the sun is reminded simultaneously of its relationship to the whole.

Although god and superstition hold a less prominent place in many of our minds these days, it’s crucial to acknowledge that for millenniums, seers, mystics, alchemists and pagans served as the scientists of their time, employing whatever tools were available to comprehend the turmoil surrounding them. Science is humble, and by definition remains open to revisions and updates as new information comes to light. The study of the physical universe, especially events as rare as solar eclipses, should be seen as an act of reverence — an offering to the infinite mystery we find ourselves living in.

These multiple exposure images were created in studio, using colored lights and cutouts, composed in camera, and finalized in postproduction.

Balarama Heller is an artist based in New York City. His 2019 project, “Sacred Place,” was published in Aperture magazine, and is a forthcoming book with text by Pico Iyer.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.