The first thing you saw at the retrospective titled “O.P. Sharma & the Fine Art of Photography: 1950s-1990s” (September 5 to October 3)—organised by the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in collaboration with Art Heritage, at Shridharani Gallery, Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi—was not a photograph. It was a watercolour, an experiment in form. In pale yellow tinged with red, the near-perfect symmetry of the shapes initially evoked thoughts of inanimate objects rather than the human body. It could have been a collection of cylindrical pillars, each crowned by an oblong capital, or a tall candle with a gently burning flame and a halo.

It was the title, Christ with Disciples, that led the viewer to “see” the painting as a depiction of human figures. The fact that one of these figures was physically taller than the surrounding ones got “translated” by the mind to mean that this was the prophet—instantly, the other forms began to appear as the disciples huddled around him. The popular associations of pillars and flames, of course, nudged the mind along a metaphorical route that aided meaning: pillars of the community, the light of wisdom. And yet the architectural quality of the image was not minimised.

In the show, the shapes in the painting were strikingly echoed by the image placed just below: Sharma’s photographic portrait of Madan Lal Nagar, his teacher at Government Arts College, Lucknow, seated in front of Nagar’s painting of the city’s iconic Imambara.

Christ with Disciples was the only painting in the show, and yet its presence added something ineffable to our sense of O.P. Sharma’s aesthetic preoccupations: an interest in form over content, the symbolic over the real, and the fictional-magical qualities of photography rather than its documentary-factual potential. The co-curators Sukanya Baskar and Rahaab Allana of the Alkazi Foundation did a splendid job of paying tribute not just to Sharma’s unusual individual oeuvre but also to a lost world of photography clubs and magazines, especially those in the tradition of what is called “pictorialist” photography.

Dharmendra in a still from Shalimar. Silver gelatin print, 1978.

| Photo Credit:

O.P. Sharma Collection

A plaque at the exhibition explained the term, quoting the art critic K.B. Goel: “What Sharma intended to prove is simple: no longer should we make the old distinction between a painter and a photographer. Now photographers, too, can ‘make’ pictures rather than ‘take’ them.” In other words, the pictorialists wanted photography to be placed on the same plane as art. To that end, they developed a series of camera-free techniques that involved manipulating the photographic negative to “create” an image. The exhibition contained examples of many such techniques, from enlargement to extreme overexposure (called “solarisation”) to re-photographing with an overlay of grids or other geometrical patterns.

On photography, though, it is always worth going back to Walter Benjamin—among the first, and still the finest, thinkers on the subject. Benjamin argues that a photograph always contains something of the real person (or place or thing or creature) that is being photographed, something that defies absorption into “art”. But more on Benjamin and photography as art later.

Congenial milieu

Sharma (b. 1937) was a Lucknow-based physics student with an interest in painting when he first discovered the camera. He has reminisced about wandering the city with it, going to the Char Bagh railway station, and that first rush of finding images everywhere. He soon joined the U.P. Amateur Photographic Association, which was filled with pictorialists who shaped his thinking. Meanwhile, the Head of Department of Physics at Lucknow University gave Sharma access to the darkroom, and the science student taught himself the rest.

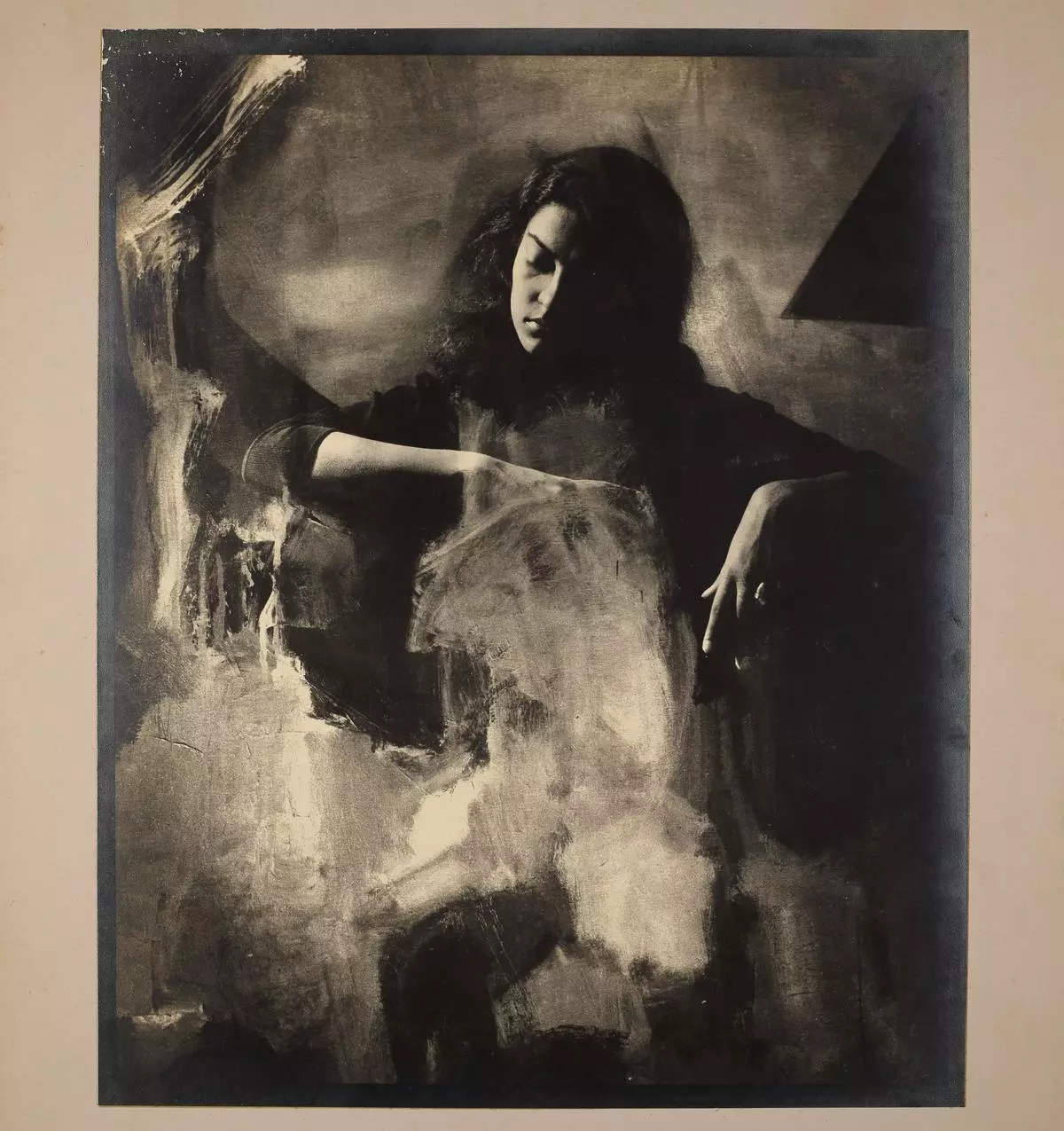

Geeta Kapur. Silver gelatin print, combined photogram, 1960s (taken 1965-66).

| Photo Credit:

O.P. Sharma Collection

In 1958, he moved to Delhi and began to teach photography alongside his own practice. His first job was at Modern School, which had established a deep connection with Tagore’s Visva Bharati University. Under Kamala Bose, the founding principal who remained in office from 1920 to 1947, great artists like Sarada Ukil and Ramkinkar Baij came from Santiniketan to teach at Modern School. Under the next principal, Mahendra Nath Kapur—a young man when he applied for the job in 1947—the school set up one of Delhi’s first photographic darkrooms. It was a milieu congenial to all kinds of art, with cross-fertilization and the heady air of the new nation creating an energy that would be hard to find today.

“In the Rain”. Silver gelatin print, C-effect, 1980-85. The original photograph was taken in Shimla from inside a moving car, and consequently developed in high contrast, using the ‘C-effect’ to accentuate the sense of motion.

| Photo Credit:

O.P. Sharma Collection

The artist couple Kanwal and Devyani Krishna had returned from their travels in the Himalaya to teach art at Modern School. The young O.P. Sharma met and married their daughter, Chitrangada, a photographer in her own right.

Also Read | DAG exhibition traces Kali’s evolution from deity to cultural icon

This cast of characters—Principal Kapur and his daughters, Geeta and Anuradha, and Kanwal Krishna and his daughter, Chitrangada—all made an appearance in the show. The straight-backed M.N. Kapur could have played a heroine’s impressive barrister father in any 1950s’ Hindi film, and there was an undeniable frisson in viewing the stunning, youthful images of Geeta Kapur, doyenne of Indian art criticism, and Anuradha Kapur, eminent theatre person and ex-director of the National School of Drama.

“Sharma’s penchant for studio portraiture extended to a much wider galaxy of stars of his time, many of them underphotographed, like Kaka Kalelkar, Gandhian writer and head of the first Backward Classes Commission.”

Sharma’s penchant for studio portraiture extended to a much wider galaxy of stars of his time, many of them underphotographed. There was, for instance, Kaka Kalelkar, Gandhian writer and head of the first Backward Classes Commission, captured with a thoughtful eye and a beard as impressive as Tagore’s; or the bespectacled Sobha Singh, civil contractor for Lutyens’ Delhi, real estate baron and father of Khushwant, known in his time as “adha Dilli da malik” (owner of half of Delhi), who looked rather more bookish than I would have imagined.

A wall of the O.P. Sharma exhibition at Triveni Kala Sangam was given over to his photographic portraits of Indian music legends.

| Photo Credit:

Alkazi Foundation for the Arts

Other images reflected Sharma’s particular interest in literature, dance, and music: there were marvellous images of the poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz, the singers Gangubai Hangal and Begum Akhtar, and the Hindi literary greats Agyeya, Yashpal, and Amrit Lal Nagar. Outside the studio, we saw the shehnai legend Bismillah Khan at his early morning riyaz in a chequered lungi, and rehearsals at the tabla maestro Pandit Kishan Maharaj’s home with all the children of the household, including the girls.

Highlights

- A retrospective of O.P. Sharma’s photographs titled “O.P. Sharma & the Fine Art of Photography: 1950s-1990s”, organised by the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts in collaboration with Art Heritage, recently concluded at Shridharani Gallery, Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi.

- O.P. Sharma is one of the finest photographers of modern India. His aesthetic preoccupations include an interest in form over content, and the fictional-magical qualities of photography rather than its documentary-factual potential.

A tour of the mid-20th century Indian cultural scene

In the 1970s, O.P. and Chitrangada were introduced by a friend, the character actor Sajjan, to the Bombay film industry. They ended up working on several films, two of them international co-productions. The show displayed gorgeous stills from these: Siddhartha, based on the Herman Hesse novel and starring Shashi Kapoor and Simi Garewal, and Shalimar, a heist drama starring Rex Harrison, Dharmendra, and Zeenat Aman.

So, the exhibition offered, in microcosm, a tour of the mid-20th century Indian cultural scene as viewed from Delhi. But documentary value was never enough to fulfil Sharma’s pictorialist ambitions. His film stills were glamorous, but in two Shalimar images, one could see him gravitating to his formal preoccupations: a grid of TV screens nearly overshadowed actor Dharmendra in one, and a black-and-white masked man crawled on a black-and-white patterned floor in the other. It did not matter that it was Dharmendra under the mask; Sharma was there for his art.

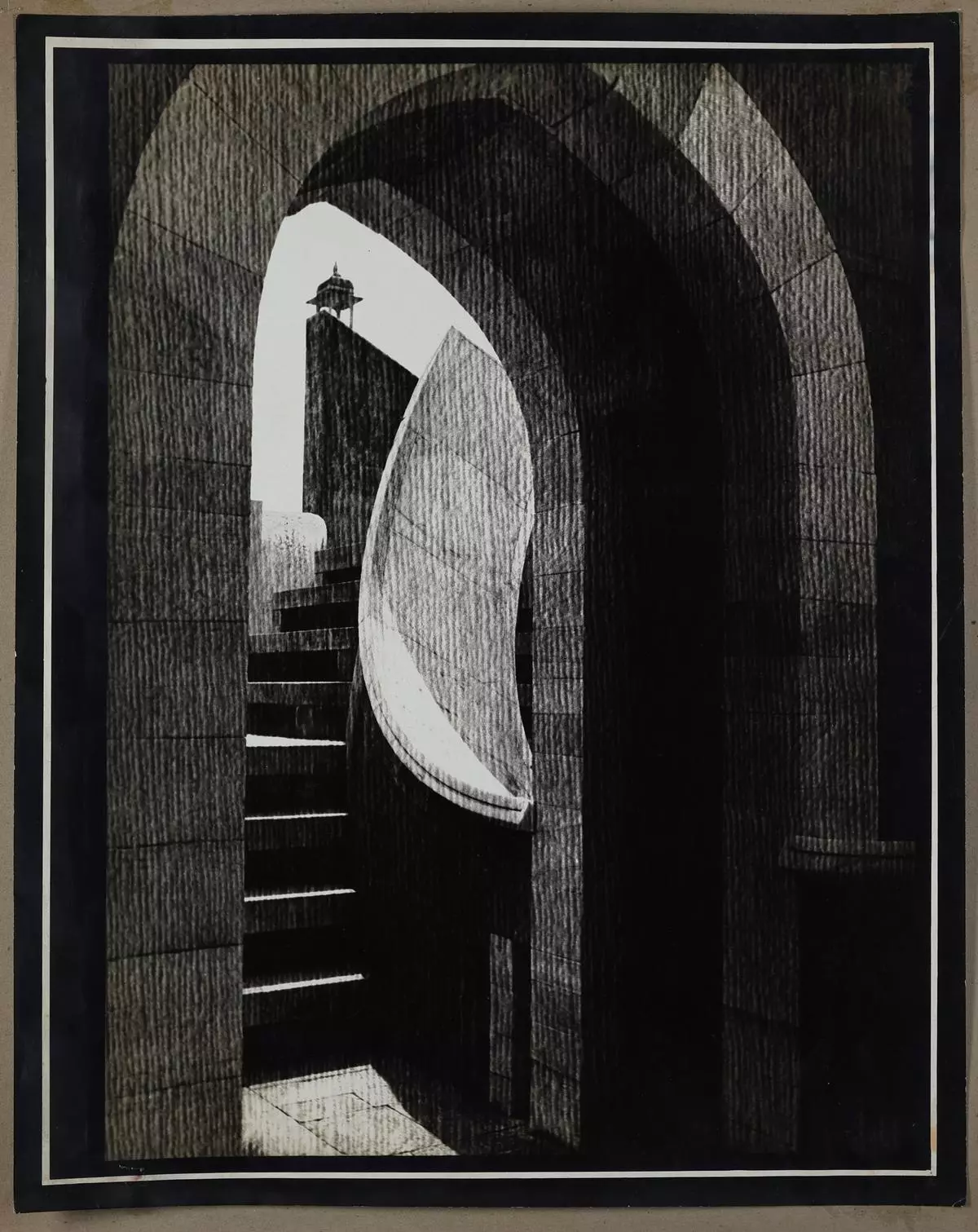

“Jantar Mantar, Jaipur”, 1990. Silver gelatin print.

| Photo Credit:

O.P. Sharma Collection

Some of the show’s most striking images were pictures that created a mood—a haunted house in a hill station, an owl in close-up—or captured form. An image of Jantar Mantar enlarged a part of the structure, making us engage with the architecture differently. Another memorable series changed our perspective on the Ellora cave temples, from the grandeur of the whole to the geometry of the parts—by focussing on angles, chinks, shadows, moonlight, parts of staircases, fragments of walls.

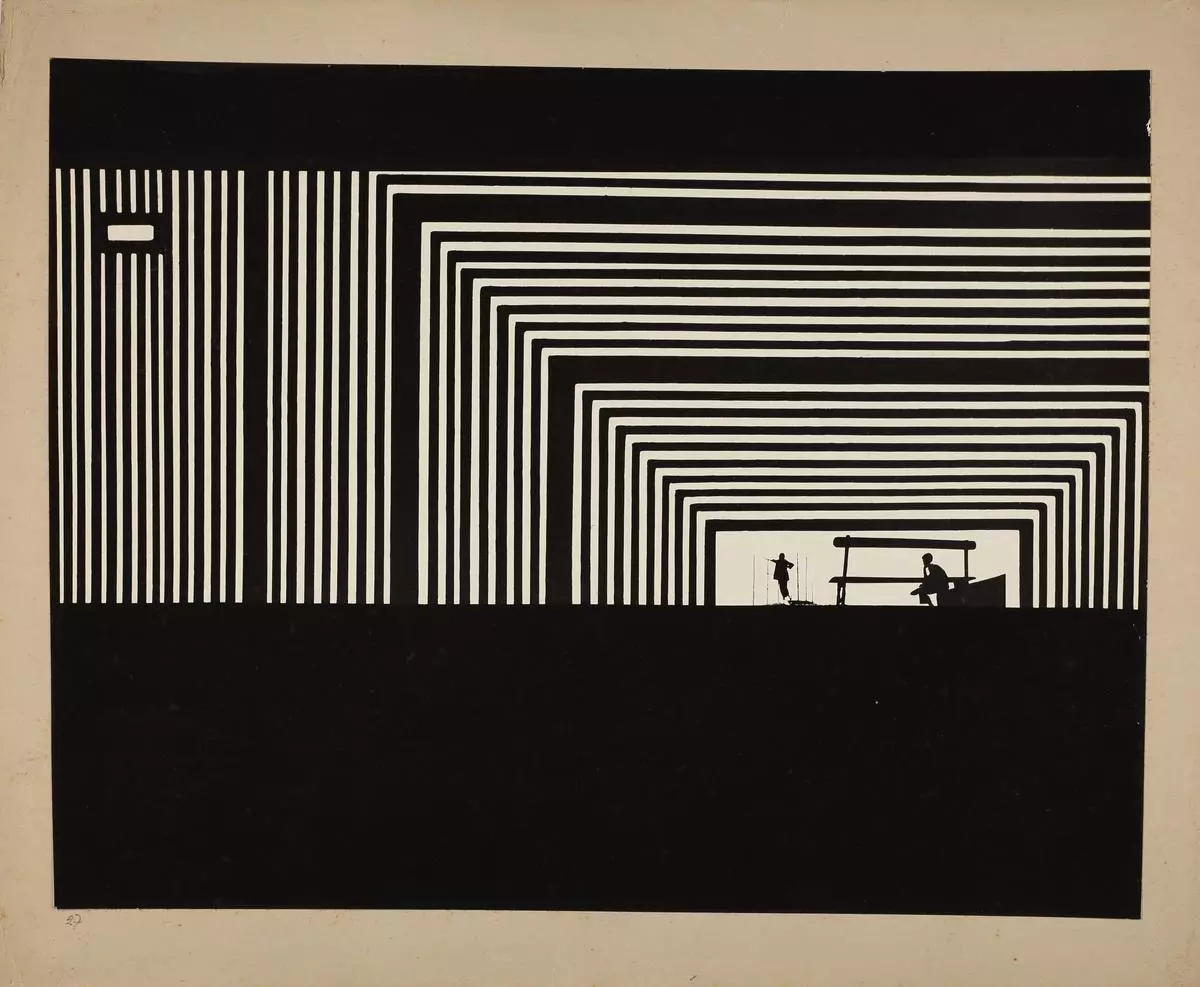

Meanwhile, a picture taken from a car on a rainy day was crafted into a black-and-white pointillist vision by the process of solarisation: a street scene like no other. Elsewhere, a visual and emotional effect was sought to be created by the addition of graphics to photographed human silhouettes: a miniature pair of human figures hemmed into a rectangular space at the centre of what seemed like a maze, or concentric black-and-white circles radiating outward from a pair of young actors on a stage.

Photographer O.P. Sharma (seated) with co-curator Rahaab Allana (standing and gesticulating) at the exhibition on September 29, 2024.

| Photo Credit:

Trisha Gupta

Sharma’s work is undoubtedly art. And yet, it was also rather wonderful to learn about the reality from which they sprang—that those actors were students performing a Shakespeare Society play at St Stephen’s College sometime in the 1970s, or that those particular fragments of stone wall were Ellora. To return to Walter Benjamin’s point, a photograph cannot completely escape the specifics of what it documents. Viewers will search a picture, always, for that “tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now with which reality has (so to speak) seared the subject”. But is that not also photography’s power?

Coming full circle

In the 1980s, Sharma started taking evening photography classes at Triveni Kala Sangam, an institution to which his connection went back to 1963, when the Shridharani Gallery there hosted his first-ever solo show of pictures. So, on the evening of September 29, when the 87-year-old arrived at Shridharani for a personal interaction with visitors to his retrospective, it felt like certain things had come full circle. Wheeled in by his son Aseem (also a photographer), Sharma was accompanied around the gallery by Rahaab Allana, who, apart from being the show’s co-curator, is from the Alkazi family, which runs the Art Heritage gallery at Triveni. They were soon surrounded by an enthusiastic crowd of people, many of them Sharma’s ex-students. Several in the crowd were photographing, taking videos. Most fittingly, though, one young woman was sketching the veteran photographer in his wheelchair, pointing out a detail.

“Black & white”, c.1980s. Silver gelatin print, combined photogram.

| Photo Credit:

O.P. Sharma Collection

Sharma would have taught photography to hundreds, perhaps thousands, sharpening eyes but also skills, in an era before the digital medium took the work—or at least the physics and chemistry—out of photography. That evening, speaking of the Internet age, he said: “Ab jo zamana hai usse accept karna padega” (We have to accept the mores of the era we are in).

Also Read | Land of dreams: A glimpse into India under the Raj

When speaking of his practice, Sharma grew animated. He offered tidbits about things like the location of a photograph (the rainy day in the picture referred to earlier being in Shimla, for instance) but did not remember the moments they were taken. That was not the point. “If you start searching your old negatives, you can make [new images],” he said. “Even when you are sleeping, all these things come in your mind. Ki iss picture ko aisa karein… [That oh, I could do this to that picture…]”.

There is another pioneering argument that Benjamin makes in his essay “Short History of Photography” (1931). “It is through photography that we first discover the existence of the optical unconscious,” he writes, suggesting that the camera “sees” the world in ways that the human eye cannot. In the light of Benjamin’s words, Sharma’s Ellora images or many of his graphic-aided or solarised ones make even better sense.

Sharma’s art emerges out of the interplay between his own unconscious—and that of the camera.

Trisha Gupta is a writer and critic based in Delhi and Professor of Practice at the Jindal School of Journalism and Communication, Sonipat, Haryana.