In March 1812, the poet Lord Byron “woke one morning” to find himself famous. He was 24 years old, and the occasion was the publication that month in London of the first tƒwo cantos of his verse narrative Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. The book’s first edition of 500 copies sold out in three days, and In the two years following its publication, some 13,000 copies were sold in Britain and abroad.

Childe Harold is a barely concealed self-portrait of Byron and of his grand tour of 1809-11, in which he had visited Spain, Malta, Albania, Turkey and Greece in the wake of publishing English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809), a lacerating analysis of Britain’s cultural and literary degeneracy, in which he includes himself in the subjects of his attack. English Bards had given him a local succès de scandale which was far eclipsed by the global public success of Childe Harold and by Byron’s subsequent best-sellers such as The Giaour (private edition 1813, public edition 1814), The Corsair (1814), and The Two Foscari (1821) and his masterpiece Don Juan (1819-24).

For Byron’s friend and fellow Romantic bard Walter Scott, reviewing Childe Harold‘s third canto five years later, the publication of the first two cantos in 1812 had had “an effect upon the public at least equal to any work which has appeared within the last century”.

Elizabeth Foster, Duchess of Devonshire, left an account of Byron’s overnight social success in a letter to her son Augustus Foster. Childe Harold, she writes “is on every table, and [Byron] himself courted, visited, flattered, and praised whenever he appears … he is really the only topic almost of every conversation— the men jealous of him, the women of each other.” The source of that jealousy: Byron’s “animated and amusing conversation” and the “pale, sickly, but handsome countenance” which is well caught in Richard Westall’s 1813 portrait, along with his carefully coiffed curls and his gaze fixed on some melancholic poetic infinity.

Byron is really the only topic almost of every conversation— the men jealous of him, the women of each other

Elizabeth Foster, Duchess of Devonshire

Over the next four years Byron became one of the most recognisable, and talked of, figures of his time. His flight into exile from Britain—at a time of great personal scandal around the failure of his marriage to Annabela Milbanke, and vicious gossip about his close personal relationship with his elder half-sister Augusta Leigh—only increased his profile across Europe.

As a writer of great personal glamour who put his character and personal experience—as a careworn but inquisitive traveller and student of life—into the lead characters of his best-selling verse narrratives, the preservation of his dashing visage to publicise his books caused readers to elide the author with the brooding, careworn, cleary autobiographical, heroes of his poetical stories.

That elided iconography of person and literary creation was a factor both in Byron’s lifetime and in the years of commemoration following his death. The engraved portraits, and a mass of memorabilia in coins, medals, ceramics and cameos, made Byron’s visage more instantly familiar than that of any other public figure—including war heroes such as Horatio Nelson and the Duke of Wellington—with the exception of his political idol Napoleon Bonaparte. That iconography is at the heart of many of this year’s events and exhibitions commemorating the 200th anniversary of Byron’s death at Missolonghi, in Greece, soon after he had embarked on what he saw as his fated duty to support the Greek people’s war of independence from the Ottoman Empire.

The mouth well-formed, but wide, and contemptuous even in its smile, falling singularly at the corners, and its vindictive and disdainful expression heightened by the massive firmness of the chin

The artist Thomas Lawrence on Byron’s appearance

The furious productivity of Byron scholarship following his death, loyally overseen by his publisher John Murray and his lifelong friend John Cam Hobhouse, caused a mass of his brilliant, self-mythologising letters to be published in Thomas Moore’s Letters and Journals of Lord Byron: With Notices of His Life (1830), allowing Byron’s opinion to weigh heavily in the scales, through his self-deprecating and often dismissive comments, when it comes to assessing the surviving portrait record. That record has been given scholarly and curatorial underpinnings by the “Bryon and the Romantic Image” chapter of David Piper’s The image of the Poet (1982)—where Piper laments that neither Delacroix nor Thomas Lawrence painted the poet, given that both had the range to capture the “dangerous” side of Bryon’s persona—by Annette Peach’s scholarly monograph Portraits of Byron (2000); the National Portrait Gallery’s 2002-03 exhibition; and Geoffrey Bond and Christina Kenyon Jones’s Dangerous to Show: Byron and His Portraits (2020). (Kenyon Jones will talk on Byron’s Image at Keats-Shelley House in Rome on 13 June.)

Piper’s frustration that Thomas Lawrence never painted Byron is sharpened by the unvarnished accounts of Byron and his works in Lawrence’s published correspondence, including an analysis, in an undated letter, of the poet’s image and appearance. “His (Lord Byron’s) vivid (and though dark) grand energy of thought awakens the imagination and makes us bend to the genius,” Lawrence writes, “before we scrutinize [his] countenance, in which you see all the character: its keen and rapid genius, its pale intelligence, its profligacy and its bitterness—its original symmetry distorted by the passions, his laugh of mingled merriment and scorn—the forehead clear and open, the brow boldly prominent, the eyes bright and dissimilar, the nose finely cut, and the nostril acutely formed—the mouth well-formed, but wide, and contemptuous even in its smile, falling singularly at the corners, and its vindictive and disdainful expression heightened by the massive firmness of the chin, which springs at once from the centre of the full under-lip—the hair dark and curling, but irregular in its growth; all this presents to you the poet and the man”.

Lawrence’s professional artist’s take offers us a contemporary aesthetic context both for the famous Byron physiognomy and for the large corpus of surviving portraits of the unavoidable, unmistakable “first poet” of his day.

Lord Byron: a poet in five portraits

George Sanders, Portrait of Lord Byron, 1807-08 Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Young voyager: the unsentimental George Sanders portrait, 1807-08

Byron commissioned this portrait, for a fee of 250 guineas, from the Scottish portraitist and miniaturist George Sanders, as a present for his mother, who thought the image of her son a good likeness. He was 19 at the time the portrait was started in 1807, an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge, making his first steps as a poet and is depicted on a wild, presumably Scottish coastline—marking the young Byron’s affection for the landscape of Scotland’s highlands and for the ancestry of his mother’s Clan Gordon forebears—a dinghy in the foreground and yacht in the background. He is accompanied by his young servant Robert Rushton. The picture is thought to record a planned trip to the Hebrides and Iceland in 1807—one that was never taken—and foreshadows Byron’s European grand tour of 1809-11.

Scholars have noted that Sanders bases the figure of Byron on the stance of the Apollo Belvedere, in the Vatican Museum, then the most celebrated and admired example of Classical sculpture. The fame the picture attained when engraved by William Finden for the frontispiece of Thomas Moore’s Letters and Journals of Lord Byron meant that it became Sanders’s best-known work. Sanders also painted two miniatures of Byron, in 1808 and 1809, which were inherited by the descendants of Byron’s daughter, Ada Lovelace, a giant in the history of computers and computing.

Less self-conscious, less sentimental than any subsequent portrait

Lionel Cust on the Sanders portrait

Byron’s mother died in 1811, after which the Sanders double portrait was kept for a time by Byron’s publisher, John Murray, at his London office, before being passed on to Byron at his London lodgings in April 1813. Following Byron’s death in 1824 the portrait came into the possession of his friend Hobhouse, who was also his executor. Hobhouse’s daughter Charlotte Dorchester bequeathed the painting to King George V on her death in 1914, and it was published in April 1915 in the Burlington Magazine by the art historian Lionel Cust, surveyor of the King’s Pictures and former director of the National Portrait Gallery. Cust finds the Sanders painting to “less self-conscious, less sentimental than any subsequent portrait” of the poet.

It is at present on show in the exhibition Style and Society at the King’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse.

- Style and Society: Dressing the Georgians, King’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, until 24 September.

Richard Westall, Lord Byron, 1813. National Portrait Gallery, London Photograph: The Art Newspaper

The celebrity poet: Richard Westall’s 1813 portrait

Richard Westall’s half-length portrait of the 25-year-old Byron was the prototype of at least three versions that Westall painted in London in the spring or summer of 1813, just over a year after the clamorous success of his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

The portrait was painted “at the request” of one of Byron’s circle at the same time as Westall was working on illustrations for a new edition of Childe Harold. Byron’s lover Jane Elizabeth Harley, Countess of Oxford, had written to John Murray in March 1813 to say that she had asked Westall to make the illustrations for both Childe Harold and the first, private, edition of Byron’s The Giaour, as well as mentioning that they think of “adding two or three more portraits”.

The Westall portrait is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, and has hung at the heart of the Romantics room since the gallery’s outstanding recent rehang. It was one of the star exhibits in the gallery’s 2002-03 Byron show which, The Art Newspaper commented, was “a perfect subject for an exhibition”, a show that “made … comparison with photographs of modern stars, such as James Dean and Mick Jagger”.

Westall’s Byron is the image of a poet and would-be reformist politician, born to opposition, set against the world, a mercurial Byron, one who the poet self-describes in a passage of Childe Harold: “Yet ofttimes in his maddest mirthful mood, / Strange pangs would flash along Childe Harold’s brow / As if the memory of some deadly feud / Or disappointed passion lurked below”. The portrait offers a close-up equivalent to the infinite stare found in Johann Tischbein’s full-length portrait of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in the Roman Campagna, painted in 1787, the year that Goethe published a revised edition of The Sorrows of Werther, a foundation text for the lonely, rebellious and brooding spirit of Byronic Romanticism.

Two related portraits of Byron by Westall, also made in 1813 but with variant poses, hang in the collection of the House of Lords, in London, and at Hughenden Manor, in Buckinghamshire, in a version acquired by the Conservative politician and two-time prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. Disraeli had employed Tita Falcieri—Byron’s Italian manservant who had been present at the poet’s death—for his own grand tour of southern Europe and the eastern mediterranean in 1830-31.

The prototype portrait by Westall was never claimed by Lady Oxford, whose relationship with Byron had ended by 1814, and was bought from the artist’s studio in 1825 by Francis Burdett, a member of Byron’s circle, a year after the poet’s death. It came into Byron’s family when acquired by his great grand-daughter Judith Lytton, Baroness Wentworth, after its sale at Christie’s of London in 1922. It was acquired in turn by the National Portrait Gallery in 1961.

Thomas Phillips’s 1814 portrait of Lord Byron in Albanian dress, from the Government Art Collection, is on show at the Benaki Museum, in Athens, hung with contemporaneous views of the Acropolis and the Parthenon, as part of a Grand Tour exhibition, along with 16 other pictures from the British Embassy, while the ambassador’s residence undergoes renovation x.com/ukingreece; Government Art Collection

The grand tourist: Thomas Phillips’s 1814 “Albanian dress” portrait

Two portraits of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips—a London-based painter known for his characterful 1807 portrait of the poet and artist William Blake—caused a sensation at the Royal Academy in London in 1814. The first was Portrait of a nobleman, a half-length portrait of Byron sporting an Elizabethan blue cloak, the second Portrait of a nobleman in the dress of an Albanian, a two-thirds length portrait of the poet in Albanian dress and head-dress. Byron started to stand and sat for both portraits in July-August 1813 and both were completed in March 1814.

The Albanian portrait of Byron has had its critics. Hobhouse thought it most unlike, while Piper in The image of the Poet likens it to “Hollywood spectacular, almost Errol Flynn playing Byron”. But the essayist William Hazlitt, reviewing the Royal Academy show, felt there was “much that conveys the softness and wildness of character of the popular poet of the East”.

While the cloak portrait—of which four versions exist, one of which hangs at Byron’s ancestral home Newstead Abbey—was engraved for John Murray almost as soon as it had been completed to be used as a book frontispiece, the Albanian dress portrait disappeared from public view the year after its exhibition at the Royal Academy. It was acquired in 1815, from Phillips’s studio by Byron’s mother-in-law, Judith Noel, for 120 guineas. She hung it at her house in Leicestershire (covered with a cloak to protect it from smoke), until it was inherited by Byron’s daughter, Ada, at the time of her marriage to Lord King (later Earl of Lovelace) in 1835.

The portrait was returned in 1835 to Phillips’s studio where the artist later made a replica of the top half of the portrait, acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1862 from the artist’s son, and a scaled-down version of the full portrait in 1840 for John Murray. It is from the Murray version that the first engraved copies of the Albanian dress portrait were made in the early 1840s, causing it to become one of the best-known images of the poet.

The original 1814 Albanian portrait stayed in Byron’s family until sold by Ada Lovelace’s great grandson Anthony Lytton, 4th Earl of Lytton, to the Ministry of Works, in 1952. It became part of the Government Art Collection in 1976, and hangs in the British Embassy in Athens. It has been the centre of bicentenary celebrations in the Greek capital, lent to the Benaki Museum for its Grand Tour exhibition, along with 16 other works from the embassy collection while the British ambassador’s residence is refurbished.

The Albanian clothes

Byron had acquired his striking Albanian costume during a visit in autumn 1809 to the warlord Ali Pasha of Tepelena (modern Tebelen), governor of the Ottoman province of Roumelia, during the second leg of his grand tour of 1809-11. “I shall never forget the singular scene on entering Tepaleen at five in the afternoon as the sun was going down,” Byron wrote to his mother, “it brought to my recollection (with some change of dress however) Scott’s description of Branksome Castle … The Albanians in their dresses (the most magnificent in the world, consisting of a long white kilt, gold worked cloak, crimson velvet gold laced jacket and waistcoat, silver mounted pistols and daggers).”

“I have some very ‘magnifique’ Albanian dresses,” he adds, “the only expensive articles in this country. They cost 50 guineas each and have so much gold they would cost in England two hundred.”

Within two months of completing the Albanian sittings with Phillips, Byron gave his costume away, sending it in May 1814 to his friend Margaret Mercer Elphinstone, a prominent figure at the Royal court. “I send you the Arnaout [an alternative term for Albanian] garments,” he writes to Mercer Elphinstone, “which will make an admirable costume for a Dutch Dragoon … if you like the dress—keep it—I shall be very glad to get rid of it—as it reminds me of one or two things I don’t wish to remember.”

The costume was re-discovered in 1962 by the Byron scholar Doris Langley Moore, at Bowood House, in Wiltshire, in the possessions of descendants of Mercer Elphinstone’s daughter Emily, wife of the 4th Marquess of Lansdowne. The costume was lent to the National Portrait Gallery’s 2002 Byron exhibition—where it was shown in company with the 1835 Phillips version of his Albanian dress portrait—and is now on show at Bowood, hung on a Byron waxwork.

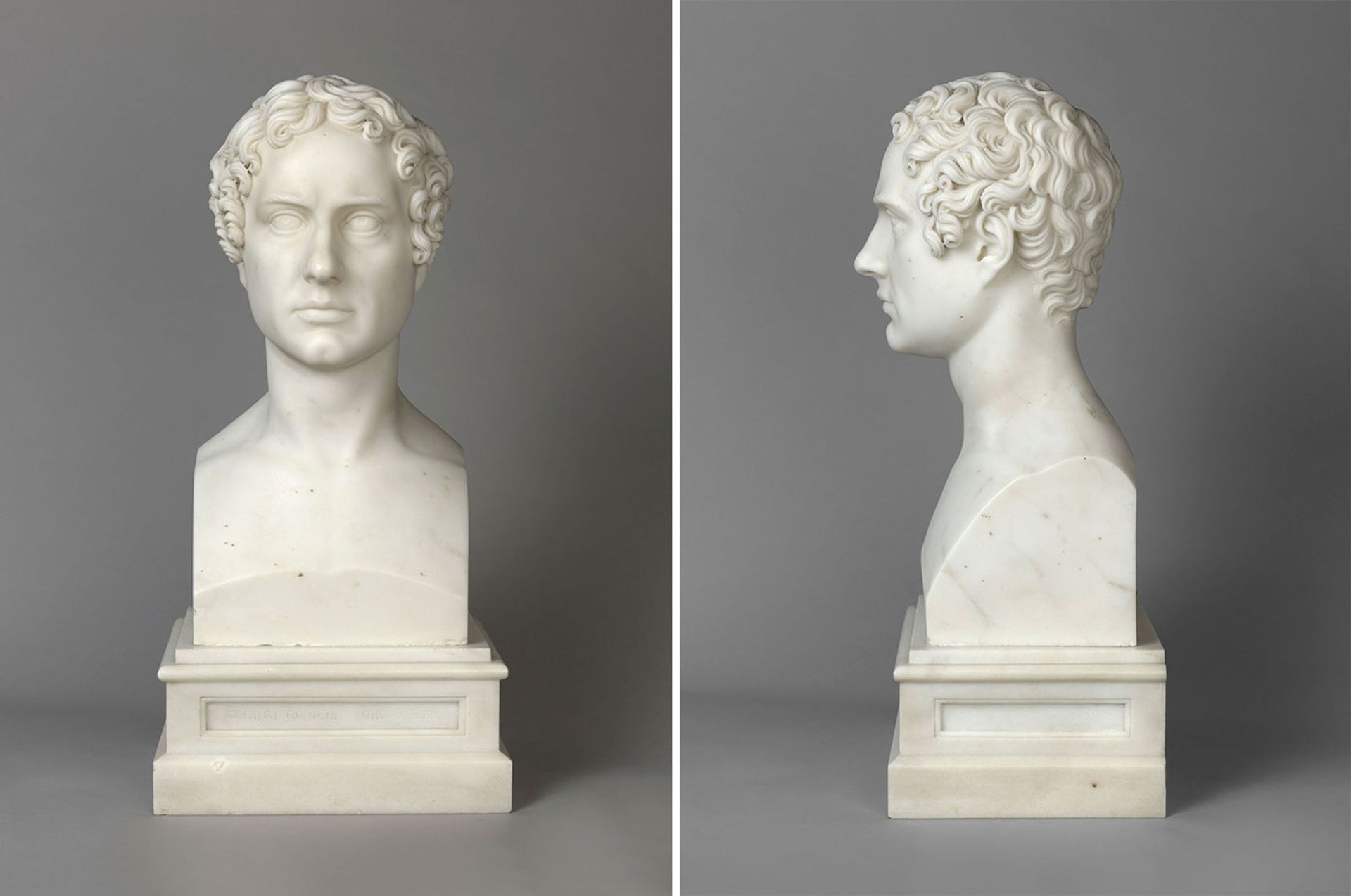

“The artist worked con amore”: Bertel Thorvaldesen, Lord Byron, 1817, seen from the front and in Byron’s preferred left profile Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

The neoclassical ideal: Bertel Thorvaldsen’s Roman bust, 1817

Byron’s complicated relationship with fame and the creation of his own image became more complex still when he found himself in Rome in 1817 and confronted with the prospect of being memorialised in stone. It was a time when he was preoccupied in his writing with the sublime in art, while working on the fourth and final “Italian” canto of Childe Harold, which was published early the following year.

In the spring of 1817, the ever devoted Hobhouse had written to commission a bust of Byron from the Rome-based Danish neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, a fashionable artist of the first rank who was Antonio Canova’s closest rival in his day and had a large, productive, studio in Rome.

Hobhouse was impressed by Thorvaldsen’s approach to the commission. “The artist worked con amore,” he wrote to Murray in December 1817, “and told me [Byron’s] was the finest head he had ever under his hand.”

Byron had mixed feelings about the associations of sitting for a sculptor. As he later wrote, he sat to Thorvaldsen only because Hobhouse wished it. “A picture is a different matter,” he wrote in Detached Thoughts (1821-22). “Everyone sits for their picture—but a bust looks like putting up pretensions to permanency and smacks something of a hankering for public fame rather than private remembrance.” In the first canto of his final masterpiece Don Juan (1819) he mused on worldly recognition: “What is the end of Fame? ’tis but to fill / A certain portion of uncertain paper … / For this men write, speak, preach, and heroes kill, / And bards burn what they call their ‘midnight taper,’ / To have, when the original is dust, A name, a wretched picture, and worse bust.”

Everyone sits for their picture—but a bust looks like putting up pretensions to permanency and smacks something of a hankering for public fame rather than private remembrance

Lord Byron

Byron reacted strongly to being captured in the idealised Roman senatorial mode of neoclassical sculptors of the day. After the first sitting with Thorvaldsen, Byron told the artist that the finished sculpture did not make him look unhappy enough. After sitting for the ranking Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini, at the artist’s request, in Pisa in 1821, he found the final result made him look like a “superannuated Jesuit”.

But Byron could be openly objective about the process, much as his thoughts were consumed with publications about the Parthenon Marbles, whose removal from Athens had so disturbed him, and by the Roman models that were everywhere around him in Italy. In 1821, he wrote to John Murray—himself the recipient of one of the variant versions of Hobhouse’s original commission from Thorvaldsen—of sculpture being “more poetical than nature itself, inasmuch as it represents and bodies forth that ideal beauty and sublimity which is never to be found in actual Nature … It is the great scope of the Sculptor to heighten nature into heroic beauty; i.e. in plain English, to surpass his model”.

According to Thorvaldsen himself, recalling the sitting to his friend the writer Hans Christian Andersen 20 years later, Byron was a very particular sitter, moving about and making faces. Andersen recounted Thorvaldsen’s words in his The True Story of My Life: A Sketch (1847): “When I was about to make Byron’s statue, he placed himself just opposite to me, and began immediately to assume quite another countenance to what was customary to him. ‘Will you not sit still?’ said I. ‘But you must not make these faces’. ‘It is my expression,’ said Byron. ‘Indeed?’ said I, and then I made him as I wished, and everybody said, when it was finished, that I had hit the likeness. When Byron, however, saw it, he said, ‘It does not resemble me at all; I look more unhappy.’ ‘He was, above all things, so desirous of looking extremely unhappy’, added Thorvaldsen, with a comic expression.”

That fidgety, face-pulling, first sitting was in May 1817. After years of correspondence with Byron, Murray and an unresponsive Thorvaldsen, Hobhouse finally took delivery of the prototype bust in London in August 1821.

Byron … was, above all things, so desirous of looking extremely unhappy

Bertel Thorvaldsen, sculptor

Following Byron’s death, Hobhouse launched a subscription in London in 1829 to commission a full-figure marble memorial of the poet for Westminster Abbey. After the British sculptor Francis Chantrey had turned down the commission, Hobhouse turned again to Thorvaldsen who accepted with alacrity. When the statue—in which Thorvaldsen modelled the head from a maquette or cast of the bust he had carved in Rome in 1817—arrived in Britain in 1835, Hobhouse campaigned long but unsuccessfully to have it stand in Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey. The dean and chapter of the abbey, who had refused to house either Byron’s remains or a memorial in 1824, remained adamant that the scandal of Byron’s personal life disqualified him from such recognition. The Thorvaldsen full-figure memorial was eventually given in 1845 to the Wren Library, at Trinity College, Cambridge, Byron’s alma mater, where it stands to this day.

The original Thorvaldsen bust—which has been much admired, as the idealised epitome of what Walter Scott meant when, according to William Hazlitt, he described Byron as “like unto a beautiful alabaster vase only seen to advantage when lighted up from within”—remained in Hobhouse’s family. It was bequeathed to King George V and the Royal Collection following the death of Hobhouse’s daughter Charlotte Dorchester in 1914.

“To sit on rocks, to muse o’er flood and fell”: Richard Belt, Lord Byron (1880). The Byron Society has launched a £360,000 appeal to move the bronze sculpture and its marble base from its isolated position on a roundabout in central London to a more accessible site on the north side of Hyde Park Photograph: Loco Steve

London’s delayed hommage: Richard Belt’s 1880 Hyde Park memorial

When the great and good of Victorian Britain, headed by the prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, formed a committee, on the 50th anniversary of Byron’s death, to commission a memorial statue to the poet, it was to right an existing wrong. The winning design, by a young London sculptor, Richard Belt, was chosen in 1877—the 27-year-old Auguste Rodin was among the runners-up in the year that he exhibited The Age of Bronze at the Paris Salon—and the finished statue, in bronze, and mounted on a massive marble plinth given by the Greek government, was installed in Hamilton Gardens at the east end of Hyde Park, central London, in May 1880.

The statue shows Byron seated on a mound, lost in thought, his chin poised in his right hand, representing the moment in Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage when the title hero is seen “To sit on rocks, to muse o’er flood and fell / To slowly trace the forest shady scene”. Down to his right sits a large Newfoundland hound, a reference to Byron’s beloved Boatswain, who died in 1808 and is memorialised in Byron’s “”Epitaph to a Dog”, inscribed on Boatswain’s massive marble memorial at Newstead Abbey.

Historians noted in 1880 that the Hamilton Gardens memorial was positioned in sight of the house, 139 Piccadilly, where Byron lived with his wife Annabella Milbanke, where their daughter Ada was born in 1815 and from which Byron went into exile after he and Annabella were legally separated in 1816.

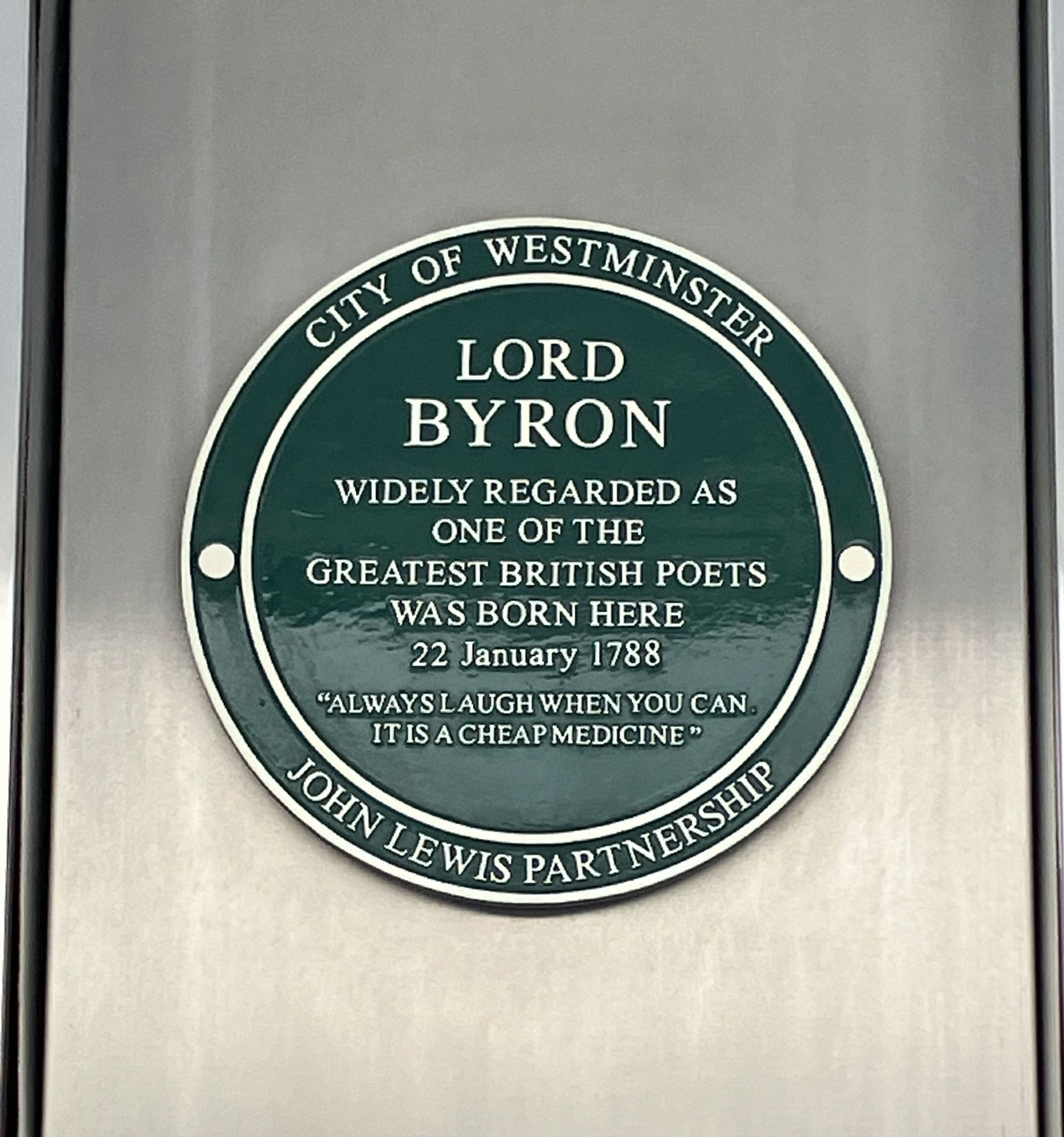

Ten years before Belt received his commission, in 1867, the house in which Byron was born, 24 Holles Street—a thoroughfare linking Cavendish Square to Hanover Square—had been decorated with a commemorative plaque by the Society of Arts, the first of its kind to be erected on any building in London in a scheme later taken on as the “Blue Plaque” programme by London County Council. The house was demolished and rebuilt in 1889, and the site destroyed by enemy bombing in 1940. The site is now covered by the eastern extent of the John Lewis department store building on Oxford Street, opened in 1960, since when the company has maintained memorials to Byron on the site.

The commemorative plaque to mark Byron’s birthplace in Holles Street, central London. The site now forms part of the John Lewis department store on Oxford Street Photograph: The Art Newspaper

The erection of the first Holles Street plaque and the installation of the Hamilton Gardens statue 13 years later meant that the city of Byron’s birth had given a measure of the formal recognition that Byron had been denied at the time of his death in 1824, when his remains were repatriated from Greece and buried in a family vault in Nottinghamshire. But efforts to install a Byron memorial at Poet’s Corner were repeatedly thwarted by abbey authorities. They included Hobhouse’s dogged but unsuccessful campaign of the late 1830s, and an equally fruitless campaign at the time of the centenary of Bryon’s death in 1924, when the dean of Westminster, Herbert Ryle, justified his refusal to accept a memorial because of Byron’s “openly dissolute life” and “the influence of his licentious verse”.

The Belt statue has served over the past 125 years as a symbol of Greek national pride. When the actress Melina Mercouri toured Europe in April 1968 to seek support for the reintroduction of democracy in Greece—a year after the Generals’ coup of 21 April 1967 and the beginning of rule by a junta government—she laid a wreath at the foot of the statue, on the day of a Greek Freedom Rally In Trafalgar Square. Alongside the wreath there stood a placard bearing Byron’s line “I dreamed that Greece might yet be free”, from his poem “The Isles of Greece”, written in 1819 and published in 1821, the year of the launch of the eight-year Greek war of independence against Ottoman rule.

In 1969, towards the end of a decade when London had enjoyed a much-vaunted moment of social and cultural liberation, Byron was finally given a memorial in Westminster Abbey, with a plaque set in the floor of Poet’s Corner. By then plans were being laid to turn Park Lane at the eastern edge of Hyde Park into a six-lane traffic system, which eventually moved the park’s eastern border west, leaving the Belt statue of Byron marooned on a roundabout just north of Hyde Park Corner.

The Byron Society this month announced an appeal to raise £360,000 to move the statue from this traffic-island isolation to a more accessible site on the north edge of Hyde Park, near Victoria Gate. The appeal is just the latest campaign to ensure that the honour given internationally over the past 200 years to one of Britain’s greatest writers and most referenced cultural figures should be likewise, and visibly, accorded to him in the city of his birth.