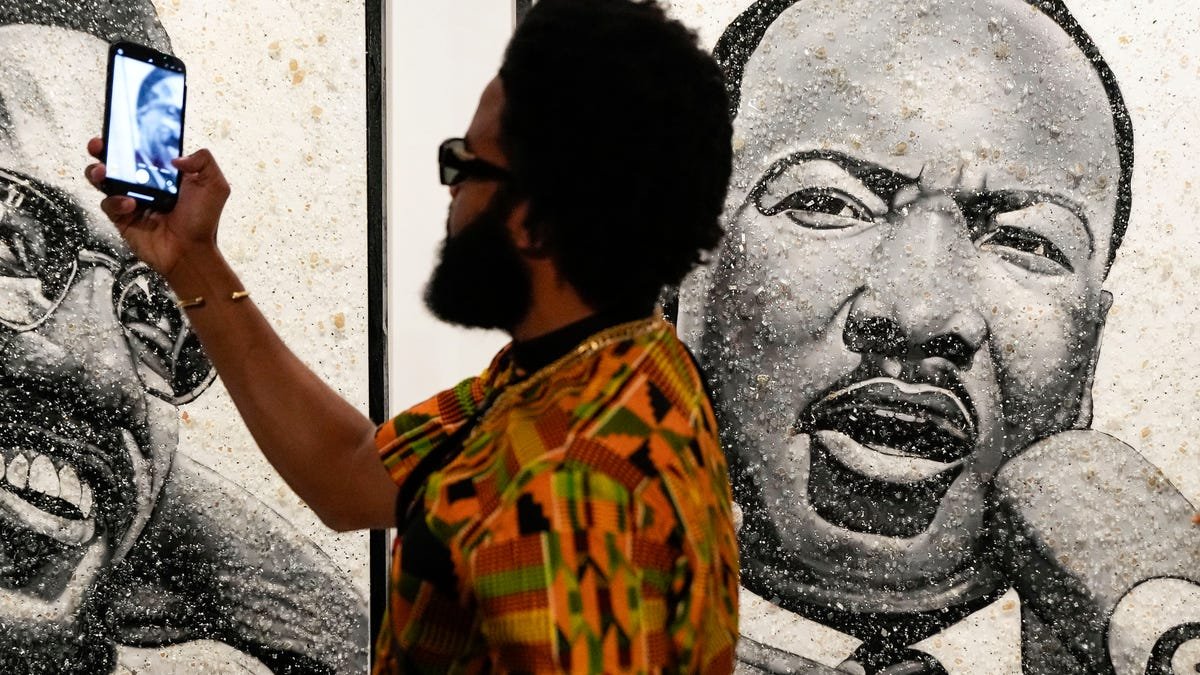

Lead ImageJustine Kurland, COUNTING BOXCARS IN THE CAJON PASS, 2010From This Train (MACK, 2024). Courtesy of the artist and MACK

There is a universalising tendency to images of motherhood (believe me, one need only browse one’s Instagram feed above a certain age to feel this). But though the idea of a mother is something society has conjured as neutral, unanswerable and benign, it is anything but. This peculiar charge to depictions of motherhood is something many artist-mothers come to understand, and perhaps wrestle with. Constance Debré – who writes the foreword for Justine Kurland’s new photobook with Mack, This Train – has articulated it. Sifting through the experience of a custody case for a son in Love Me Tender, Debré writes, “If people want to believe that women have a connection to the Moon, to nature, a special instinct that forces them to cling to motherhood and give up everything else, that’s their business. But I’m not interested. There’s no such thing as a mother … There’s only love, which is completely different.” Motherhood, as Debré formulates it – as “status, an identity, a form of power, a lack of power, a position, dominated and dominant, victim and persecutor” – is inextricable from the Madonnas and cereal advertisements that have made up its visual representation through time.

Just as she radically resituated girlhood in Girl Pictures – with its strikingly independent collections of off-grid teenage girls – Kurland does the same with motherhood in This Train. We see a long-haired boy, alone in the foreground, his only company a thread of boxcars in the primary colours of childhood, and capitalism; a dark-haired woman and the same little boy, in a field of gold-on-green wildflowers, too distant to tell if they are locked in a dance or a tussle.

“The book is really a love letter to my son,” says Kurland. “But at the same time, there’s all of this violence embedded in the landscape that’s built into that.” Presented in a tactile and weighty concertina form, the book’s fabrication creates two halves – or rather two faces – that reflect those dual narratives: one side the personal history, on the road with her son; the other a series of trains cutting through landscapes that seem to obfuscate the personal. As the alternate foreword to This Train by writer Lily Cho explores, such obfuscation exerts its own power: reflective of the America that only built such mighty routes off the back of the suffering and deaths of Chinese immigrant workers.

Though we might see him for the first time here, Justine’s son Casper has always been there: accompanying Kurland and her camera throughout the several-month-long road trips she took for her photography from 2005 to 2011. He was in Of Woman Born, for instance, her series of other mothers and other children staged among natural landscapes across the USA. And while notions of mothering are less evident in the extra-familial gangs of Girl Pictures, I still think of her as a kind of photographer-shepherd when I think about the making of those images. “I would scan the locations before I would find the girls,” she recalls. “So even then, there was always something about the landscape itself as holding stories and histories. But there’s also the way that a landscape presents itself as an allegory. It takes on a temporal sense, it can hold a figure; you can nestle up, or enter into it. Or the way it has a line that knits the foreground with the background. Going on these road trips, I was really attuned to that.”

If Casper and Justine are a pair held by a landscape in This Train, it is one that doesn’t always feel like it is holding them in safety; but among the indifference of the great American plains, they seem to hold each other within it. When I connected with Kurland on Zoom to talk about This Train, she was in Joshua Tree, with unmistakable Californian light streaming through her window – some vastness to explore just outside the frame, which is how her photographs tend to feel.

Below, Justine Kurland talks about the making of This Train in her own words.

“When my son Casper was born, I didn’t know how to be a mother and continue working as an artist. I didn’t have a very good plan for that. I never thought, ‘Oh, I’m just going to bring my kid on the road.’ But what else was I going to do? My photography was how I was supporting us. Since he was six months old, we were on the road eight months of the year. We would come back for a couple of months in the spring, and a couple of months in the fall, but really, he grew up in a car seat.

“At some point, he got very excited about trains. A lot of the highways in America go by trains, and there are all of these railroad museums. He was fully obsessed: had to know everything about the track signage and the different types of engines. So I thought it was only fair if I was going to bring him on these road trips that I photograph the trains, too.

“What’s interesting about that – and about photography generally – is the contingency that when you intend to photograph one thing, with one intention (I’m a single mom, my kid loves trains), I’m also at the same time photographing everything that goes with the trains. People talk about the trains as a first wave of the Anthropocene: this moment of the emergence of steam engines has the beginnings of climate change embedded within that. And the first landscape photographs of the United States were these government surveys. They were about laying the train tracks so that the settlements could push further and further west. So, there’s this whole history along the trains that is both a photo history and a settler colonial history involving the genocide of Indigenous people.

“Images don’t have fixed meanings. At the time, in this bubble with my kid, I would see the trains the way he saw the train, and there’s something (different) about looking at them now. It’s like milk cartons with a picture of a missing child at the side, using what was previously a family photo. In the same way, the same picture that’s this joyous moment of my kid’s childhood is also a moment of deep, dark American violence. That was the thinking behind the accordion book: that there’s always a shadow side. Like the stories a family will tell about itself, but there are always secrets.

“Constance [Debré], in her very French way of writing, says [in her foreword] that this is not a family album. I love that she wrote that. I do actually think it is a family album. But there’s a really interesting thing that she presses into it, about the difference between the autobiographical and the personal, right? Where the autobiographical is like the facts of the family album: this is my child, we’re in a state park, we’re in Montana. But I think the personal here is this affective emotional sense of what it is to be lost and alone in the world, and what it is to yearn for a sense of home that doesn’t exist, or yearn for a sense of family that doesn’t exist. I think of the personal as more of a shared emotional state, like the difference between a memoir and an autobiography.

“There’s really no difference between my life with Casper as a mother and my life with Casper as an artist. It’s an imposed binary – how could they be two different things if I’m just with him 24/7? How could he not permeate every part of my conscious psychic space? When I think about what connects all the bodies of work that I’ve ever made, it’s really about this idea of creating space for women and thinking about the ways that women are disempowered. And this has a lot to do with the idea of the ways that they’re isolated from each other. There’s something about the work that I was doing, that was thinking through whether there was a way to represent motherhood that could break free from the ideological ways that it’s weaponised against women.

“When I was at Yale, in graduate school, Laurie Simmons was my teacher. And I remember her talking about how you had to pretend that you didn’t have children. You had to just never mention them. Think about all the things artists put themselves through: maybe we say their drug addictions make them better artists, or their world travels, or just the fact they are well-read. If in fact, raising a child is about this constant sense of empathy and nurture and ambivalence, and there are all of these ways that it pushes and pulls you: why wouldn’t child-rearing make you a better artist?”

This Train by Justine Kurland is published by Mack, and is out now.