I Am Who I Am Now: Selections from the Bengali Photo Archive18 Images

Over the last few weeks, the walls at the Four Corners gallery in East London have doubled as an emotive photo album of the city’s East End, an area that has long served as a home for Bangladeshi immigrants. Procured from the Bengali Photo Archive, the gallery walls display photographs spanning the last 50 years of anti-racist protestors storming the streets, of children in striped jumpers playing football, of the youth clubs that used to populate the area, and portraits of community members sitting in front of patterned wallpaper. “We are invited into the houses of aunties and uncles and can appreciate the candid snapshots of domestic life, celebrations and social gatherings,” co-curator of I Am Who I Am Now: Selections from the Bengali Photo Archive, Julian Ehsan shares in an interview with Dazed. “There’s a greater sense of familiarity and ease in how the camera and the lens are employed by the photographers displayed in the show, which allows us to gain intimate visions of life in the East End that others can’t fail to capture as easily.”

In the past, exhibitions of vernacular photography, especially those that concern the lives of marginalised communities, have often been critiqued for their tendency to border on the voyeuristic. Thanks to the team at Four Corners, working alongside Swadhinata Trust and Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, I Am Who I Am Now avoids this through community curation and collaborative archive-making. This modality of the show was inspired by the Feeding Black exhibition at the Museum of London, which directly incorporated the lived experiences of community members into the show by allowing them to tell their own histories.

At Four Corners, Ehsan began this process during the initial stages of putting up the show, asking members of the Federation of Bangladeshi Youth Organisations (FBYO) to select images captured by Lloyd Gee to respond to. “I was really moved during my workshop with the former FBYO members. We spent the day going through old images Gee had donated to us, recollecting the importance of certain activities, events, buildings, and people,” he shares. “I was especially inspired after listening to their stories from their time in the group and how they fought to make changes in the community. To me, this underscored the importance of documenting and spotlighting everyday histories that might have otherwise gone unrecorded, as some might consider them mundane or unworthy. However, these histories are critical to understanding the Bengali community in Tower Hamlets today.”

The success of this process with the FYBO led to the exhibition becoming an exercise in co-curation. Over three months, Ehsan ran workshops with volunteers from the BPA who were involved in shaping how the exhibition would look and sound. “We worked on the images and quotes that would be included, which themes would guide the show and even the title which was inspired by photographer Mayar Akash, who reflected, ‘I am who I am now’ because of his experiences working in youth work settings in the East End.”

Cultural institutions have extensively explored the archive and the ways it brings memory into the present. In I Am Who I Am Now, the photographic archive is similarly alive, partly as it animates the joys and struggles of the community it is built around, but more crucially because it has been worked through and recalibrated with the help of the community. The archive hasn’t just been passed through the hands of cultural workers but through the people who constitute it. Ehsan reiterated the importance of this curatorial decision: “The exhibition and curatorial mission sought to amplify the voices of people who submitted to the archive or appear in it. This stems from the idea of social history that ‘everyday’ people and their stories should be celebrated. It’s been a real honour to see this play out in real-time when I overhear visitors saying they recognise locations, people, settings and surroundings in the images.”

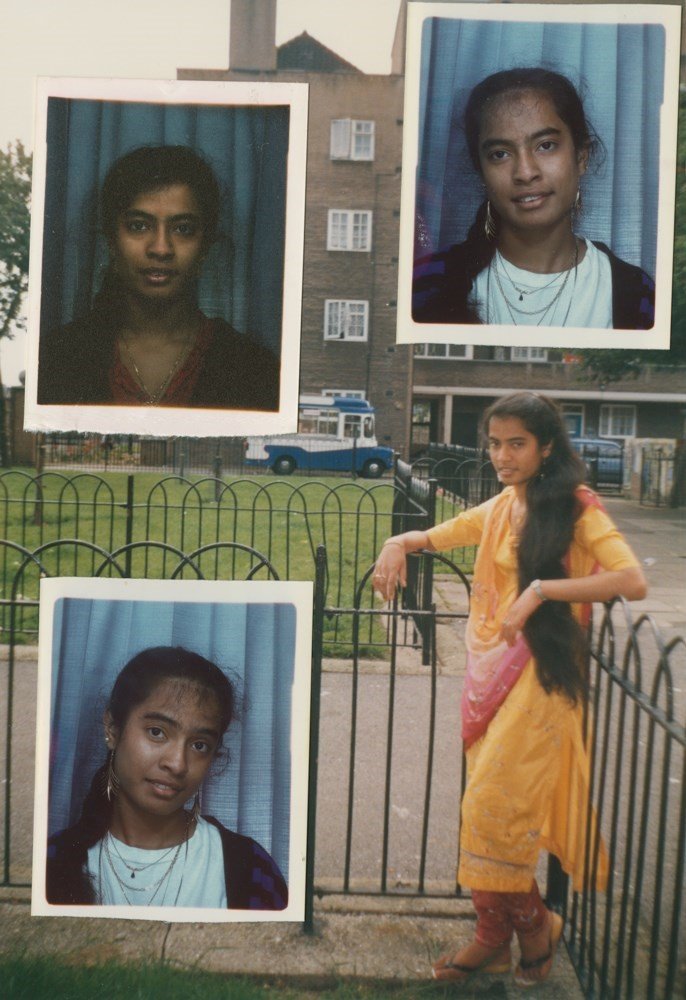

While candid photographs of social life and youth clubs from the 80s and 90s are a focal point in the show, Ehsan’s favourite photograph from the exhibit is surprisingly a collage of Shahnaz Siddiqa-Baeg posing in front of the council estate she lived in the East End (above). Likening the collage to a treasure trove of clues about Baeg’s interior life, he notes how each aspect of the image – from the garments she chose and her hairstyles to the use of studio space – speaks to how Siddiqa-Baeg wanted to represent and express herself. “For me, the photo and how it arrived at the archive encapsulates the exhibition perfectly,“ says Ehsan. “Shahnza Siddiqa-Baeg’s son, Tanbir Mirza-Baeg, meticulously scanned hundreds of his family’s photographs and documents for the BPA. The final room features many of her family and younger self’s portraits, and Tanbir even curated his own vitrine of objects and documents from his nana-ji [grandfather]. The images from Shahnaz, speak to our ethos of collaborative exhibition-making and letting Bengali community members take agency in how they are represented.”

I Am Who I Am Now: Selections from the Bengali Photo Archive are on view at Four Corners until August 10, 2024.