High above cities around the world, artist Isaac Wright has illicitly taken photographs from perches that few people will ever grace. The self-taught artist and urban explorer has climbed New York City skyscrapers, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, and even the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The resulting images are nothing short of awe-provoking, like the photographs he took of the RAMS in September, as the graffiti artist rappelled down a 43-story abandoned New York City skyscraper to spray paint his name across the construction shed high up on 45 Park Place.

RAMS’s piece was stunning, but Wright’s documentation of the ephemeral work showed off not only its bold lettering, but the beauty of the surrounding skyline, the sky gradually lightening as night wore into morning. RAMS clearly was at work for hours, giving Wright time to take photos from various different vantage points atop neighboring buildings.

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph of graffiti artist RAMS on the side of 45 Park Place. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Watching RAMS work was really awesome,” Wright told me. ”He’s taking graffiti to literal new heights, and it’s really sick to see.”

For some photos, Wright shot from above, capturing RAMS silhouetted agains the glowing lights of the Santiago Calatrava-designed World Trade Center Oculus. Carefully composed images show the artist suspended high above the city streets, with landmarks such as the Woolworth Building and the Manhattan Bridge in the background.

Wright hopes viewers appreciate not just the audacity of both the graffiti artist and the photographer documenting him, but the artistry of the images themselves.

RAMS rappelling down the side of the abandoned skyscraper 45 Park Place to spray paint his name on the building. Photo by Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright.

“I want to bring urban exploring to the fine art world,” Wright said. “I want to see it taken seriously. I want to see it reach the institutions.” (He sells some work through New York’s Robert Mann Gallery, which specializes in photography, but is interested in showing alongside artists in other mediums.)

But in pursuit of his art, he has also faced serious legal consequences. An investigation launched by a single, overzealous Cincinnati detective into Wright’s nocturnal adventures led to a nationwide warrant for his arrest. Where Wright saw clandestinely entering high-profile buildings as an opportunity to make art, the police saw a national security risk and a potential terrorist.

In a scene more befitting the pursuit of a mass murderer, Arizona police launched a manhunt, shutting down the highway and sending a helicopter to the scene. Officers surrounded Wright’s car and arrested him at gunpoint in December 2020. A second arrest, with 16 officers and five bomb dogs deployed at the behest of Cincinnati police, came five months later as Wright entered Kentucky.

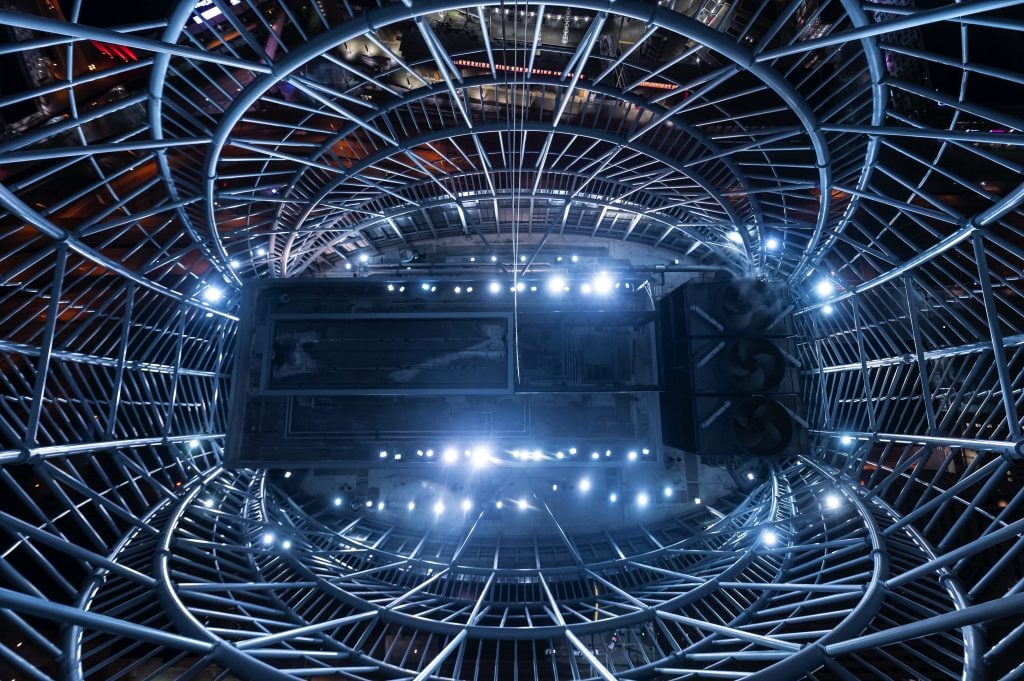

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph of Great American Tower, Cincinnati. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Wright was accused of illegal entry and property damage—cutting wires on security cameras and breaking locks. For this, he faced 30 felony charges across five states, with a potential 50-year prison term.

Detective Jeff Ruberg had linked photographs on Wright’s @driftershoots Instagram account to an illicit visit to the top of Cincinnati’s Great American Tower. From there, Ruberg imagined the worst case scenario about his suspect, a Black military veteran.

Ruberg alerted law enforcement agencies that Wright had PTSD, special operations training, and was potentially armed. (He was not.) But why did Ruberg did to such great lengths, and employ so many police resources, to pursue an artist for crimes that included such unthinkable acts as… sneaking into a baseball stadium?

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph of Great American Ballpark in Cincinnati. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“The honest answer is I don’t know—I just know that living through it was hell,” Wright told me. ”Having my military background used against me was… betraying.”

Before I knew his whole story, I had assumed that Wright, like RAMS, would insist on secrecy, an anonymous artist who hides his face to avoid run-ins with authorities. But his legal ordeal, which saw him spend over 140 days behind bars—only to accept a plea deal with no prison time—thrust Wright into the spotlight in the worst possible way.

“I wanted to be great as an artist, and I pursued my art in a way that shouldn’t have brought all of that on my head,” Wright said. “It was brutal, really brutal. But I survived it. I won the cases.”

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph the the top of Steinway Tower in New York. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The artist’s origin story dates to May of 2018, when he was stationed at an Army base in Louisiana. He had stumbled upon urban explorers on social media and woke up one night inspired to give it a go.

“I had this dream. And it told me to take my camera and go to Houston,” Wright said. ”I got there at like one in the morning and I was walking around downtown and I saw this skyscraper under construction. I just hopped the fence and I went up.”

The experience was amazing, even if those first photos, Wright admits, were bad—an afterthought, really, compared to the unique, peaceful feeling he got being alone in these spaces, beautiful but off limits.

“I’m not an adrenaline junkie. I don’t get high off stuff like this. In fact, it makes me feel very down to earth,” Wright said. “I was diagnosed with PTSD. I have bipolar disorder. Climbing has been a really great outlet for me for those things.”

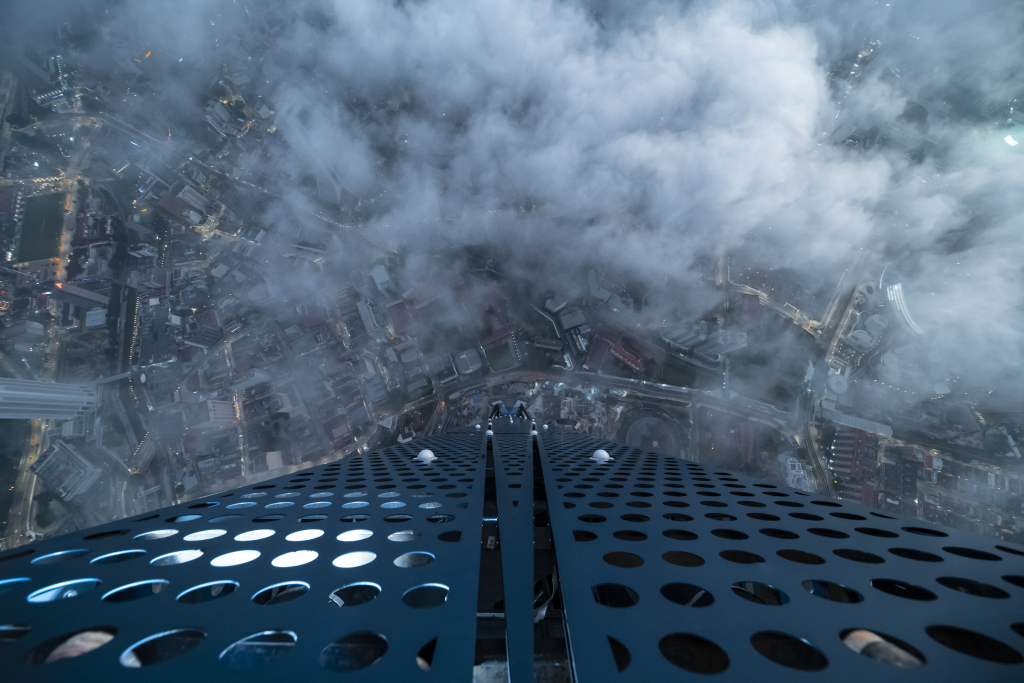

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph of Merdeka PNB 118, the world’s second-tallest building, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Photo courtesy of the artist.

When asked, Wright was hard-pressed to chose his best urban exploring memory. “Gosh, there’s so many—some that I would like to say, but I can’t say for legal reasons,” he admitted. ”I’ve climbed almost 50 bridges across the world, including the highest bridge in the world in China. I’ve climbed Christ the Redeemer in Brazil.”

In March 2020, Wright was honorably discharged from the Army, after six years as a chaplain’s assistant. He’d been getting more serious about his photographs, which were improving all the time—and needed a new way to make money.

“This was all that I wanted to do. So I started to sell my work. I was only selling them for a couple $100 a pop at the most. But I was getting much better as a photographer,” Wright said.

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph atop Christ the Redeemer in Brazil. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Then came the arrest. It was traumatic and triggering, but in a way, it was good for the work.

“It was almost like a shift happened while I was incarcerated. I got a lot better, even though I wasn’t taking photos. And I really feel like it was a spiritual thing,” Wright said. ”After that, I really started to make images that I was super proud of.”

And it was his art that allowed him to mount a successful legal defense. Over a year selling NFTs of his photography collection “Where My Vans Go,” Wright was able to make $10 million, including a $27,940 lot at Sotheby’s New York’s 2023 “Contemporary Discoveries” sale. It was enough not only to pay his lawyers, but to donate $500,000 to support bail reform. (Wright was initially held on $400,000 bail, before a judge reduced that amount to $10,000.)

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph of the Eiffel Tower. Photo courtesy of the artist.

As soon as he was released from house arrest, Wright was back out there, once again finding entry points through fire doors, maintenance elevators, and emergency exits. Despite the risks, the drive to make his art was too strong.

“As a artist, making a good photograph is everything,” Wright said. “It allows you to relive that memory and allows other people to live inside of it. My life is [that of] a fine artist. I’ve got to take good photos—it’s just a passion.”

In 2022, he went to Paris and climbed the Eiffel Tower. From there, it was on to Egypt, where the pyramids lay as if waiting for him. Wright also summited the world’s second-tallest building, Merdeka 118 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia—it was one of the rare times he was caught, but the developers did not end up taking any legal action.

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph atop the Great Pyramid of Giza. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Wright knows the risks he is taking.

“The pyramids were very daunting, especially knowing what would happen if you got caught. Egyptian prisons? Very rough. And you know the police are not friendly,” he said. “You have armed guards at all four corners. You have to be extremely, extremely precise with how you go about getting up and down.”

“Getting to the top was one of the best thrills ever because the climb up is exhausting,” he added. “There were just tens of thousands of names inscribed on the pyramids, some carved in languages that don’t exist anymore. I mean, it’s just one of those places that makes you feel incredibly small—and you realize how big of a world we live in.”

Isaac “Driftershoots” Wright’s photograph atop the Great Pyramid of Giza. Photo courtesy of the artist.

As appreciation for Wright’s work has grown (he has 203,000 Instagram followers and 128,000 on X), he’s begun getting opportunities to stage legal photoshoots at high-up spaces. The CEO of Cincinnati’s Fifth Third Bank bought three photos at a local gallery, then invited Wright up to the roof of company headquarters, the city’s fifth-tallest building.

“I think within two years, I’ll be doing this legally all over the world,” Wright said. “On the New York Times Tower, I shot my friend climbing with a double rainbow in the background, and a lightning bolt. And that was unscripted. That was completely illegal. Crazy. Imagine if you have legal access. You could shoot the most incredible photos ever, really.”