Artists have been fascinated by the night sky and its dazzling cosmos for centuries. From Van Gogh’s trippy The Starry Night (1889) to Théodore Géricault’s eerie, green-tinged After the Deluge (1819) and Georgia O’Keeffe’s geometric Starlight Night (1917), many have attempted to capture the inherent mysteries of the universe as viewed from the ground. Some have taken it a step further, with Jeff Koons launching his mini sculptures to the moon using an un-crewed Odysseus lander this February.

So why are these artists continually drawn towards space? With a solar eclipse just behind us, we explore some of the most exciting contemporary artworks that look to infinity and beyond.

Angela Bulloch

Angela Bulloch, Night Sky Blue: Jupiter & Saturn in Capricorn.12 (2020). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

Made up of visually stunning LED light installations, Angela Bulloch’s Night Sky pieces (2010), which mimic bright stars, may on first glance seem to match the image we have of the cosmos from the Earth. But they are much more than that, and in fact show how the universe would look from other positions in space. Each view is generated using computer simulation algorithms, based on Celestia software, which is used to simulate space travel.

These works de-center the Earth and humans from the prime viewpoint in the galaxy, offering the opportunity to step outside of our self-aggrandizing position and consider different perspectives from other planets and dimensions. “It addresses fundamental questions such as ‘where are you in the world?’” the artist said when her Night Sky: Venus and Mercury showed in the Basel cathedral adjacent to the city’s marquee art fair in 2010. “The work provides a [virtual] representation of the universe, showing [the planets] Venus and Mercury. I’ve made something real from a virtual standpoint.”

Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans, Venus transit (2004). Courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, Galerie Buchholz, and Maureen Paley.

In previous centuries the “transit of Venus”—when the planet crosses over the sun, appearing as a small black dot from Earth—was the only way for scientists to check our exact position in the solar system. There are more tools to make this possible at any time now, but it’s still a rare event; once in a lifetime for many. Wolfgang Tillmans captured the transit of Venus on camera in 2004, the first time it had crossed the sun in this way since 1882.

“Observing the 2004 transit through my telescope, which I still have from my astronomy-obsessed teenage days, had no scientific value, but it was moving to see the mechanics of the sky,” Tillmans wrote in 2011, when he selected Venus Transit (2004) as his personal best shot. “To see a planet actually move in front of another gave me a visual sense of my location in space… Given the high magnification of the telescope it is difficult to avoid shakes. In all, I managed to take seven good pictures.”

Betye Saar

Betye Saar Celestial Universe, (1988). Courtesy Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Betye Saar’s sumptuous Celestial Universe (1988) captures the magic of the night sky, combining the beauty of our view of stars from the Earth with the mythical allure of the zodiac. Hand painted on deep blue silk taffeta, her work maps iconic imagery, including astrology with intricate star maps and figures of famous constellations that originate in Greco-Roman mythology. While many artists look to the stars with thoughts of the future, Saar’s work captures the deep history of symbolism that lies in our skies, and the many ways in which humans have attempted to interpret he stars.

The artist has been fascinated by sky maps and star charts since she was a child, and this work has appeared repeatedly in her exhibitions since it was made. A 2016 edition created in line with Saar’s 90th birthday also highlighted the deeply personal connection she has on an individual level with the expansive galaxy: the work A Handful of Stars was a solid bronze mold of her hand placed on a walnut base, with celestial forms embedded in the palm. Like many of the artists who work with the cosmos as source material, this captured her dreams of reaching out and holding the universe in her hand.

Thomas Ruff

Thomas Ruff 22h 58m / -40° (1992). © Thomas Ruff & ESO / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024

Courtesy Sprüth Magers

Some of Thomas Ruff’s large-scale Sterne (Stars) photographs (1989-92) show the galaxy in such detail that they could be mistaken for images of a cloudy day. The cosmos variously twinkles and blinds in his mighty black-and-white works, taken in exquisite detail from observation shots at Chile’s European Southern Observatory (ESO). These works highlight the power of technology in seeing the world around us, providing far more detail than the naked eye, hampered by light and air pollution, ever could.

“It’s also a homage to Karl Bloßfeldt,” the artist said in a 1993 interview. “In the twenties he took photographs of plants to explain to his students architectural archetypes. So he was a researcher but the way he represented his intention with the help of photography made him an artist. I like these crossovers.”

Zhao Zhao

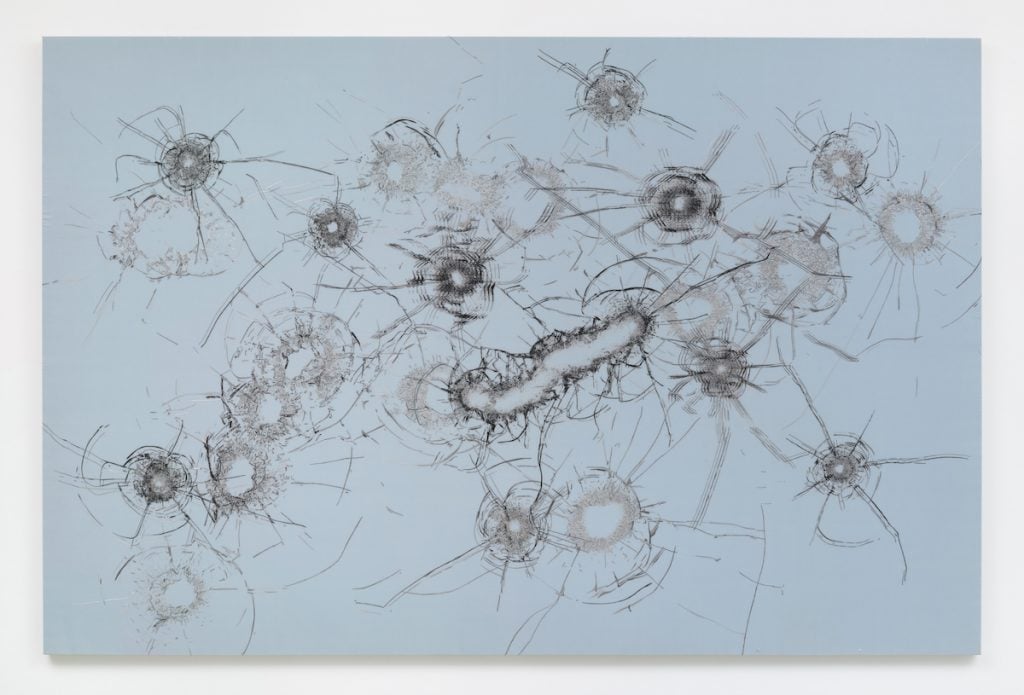

Zhao Zhao Constellation 6 (2013-ongoing). Courtesy the artist and Robert Projects Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Not all images of the night sky are so direct. Zhao Zhao’s Constellations (2013–ongoing) are informed by his personal experience of hitting his head into the windscreen of his car during an accident in 2005 as well as the visual remains of events at Tiananmen Square in 1989. To recreate the effect, he first shot into panes of glass and painted the results in swirling oil paint, which he then interpreted using intricate silk embroidery with the help of his mother.

The starburst patterns and energy of the works reminded him of the galaxy, and he embraced the conflict between the beauty of the pieces and their explosive creation, drawing parallels with the intense collisions that form the sublime cosmos.

The works are characteristic of the artist’s multi-layered approach, in which something deeply political uses the language of something seemingly disconnected (the night sky), to create a powerful visual metaphor.

Suki Chan

Suki Chan, Lucida II still. Courtesy the artist.

In Suki Chan’s film Lucida II (2017), the limits of the human eye and its connection with the mind and vision are explored in detail through her work with scientists and psychologists. The film begins with artist Annie Fennymore narrating her own experience of losing her eyesight. As her voiceover finishes, the screen flashes to a powerful image of the sky at night, evoking the wondrous potential of human vision. The work draws on the emotional connection we have the night sky, something that remains physically out of reach for a vast majority of us, but that many find meaning in gazing upon.

It also highlights the awe-inspiring nature of vision itself, which allows us to see the complexity of something so unfathomably enormous as space. “The more I investigated perception and how the brain processes information, the more miraculous and incredible it became,” she said in a 2016 interview. “It is quite astounding how impoverished and compressed information received via our senses can yield a coherent, high resolution, detailed and multi-dimensional world.”

Trevor Paglen

Trevor Paglen with an early prototype of Orbital Reflector. Photo courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery and Metro Pictures/Nevada Museum of Art.

When Trevor Paglen launched his artwork into space in 2018, astronomers were not happy. The sculpture was planned to be visible from the earth for a few months, functioning as a human made star. “It’s the space equivalent of someone putting a neon advertising billboard right outside your bedroom window,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

As the artist saw it, his shiny, $1.5 million ‘Orbital Reflector’ was a mirror of human existence. “When we look up into the starry night sky, we tend to see reflections of ourselves,” said the artist in 2018. The work ended up getting lost in the void in 2019, and some looked to Donald Trump’s 35-day government shutdown as the reason why. Nevada Museum of Art had been working with officials to greenlight the release of the balloon at the correct time for safe trajectory, but communication was paused during the shutdown.

Vija Celmins

Vija Celmins, Night Sky (Ochre) (2016). Private collection © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery.

Many of Vija Clemins’ works recreate elements of the natural world that are too intricate or vast for the human eye to properly take in. An ongoing series of works look to the night sky, meticulously detailing hundreds of stars using oil on canvas, graphite on paper, and printmaking techniques. These images have been sourced from satellite images, which already show more detail than the human eye can comprehend when looking at the sky. Her final paintings are smoothed to a velvety finish, with each layer sanded down as she works.

These pieces highlight the engulfing nature of space, with no human point of size comparison or horizon in these pieces, just broad expanses. But there is a sense in these works that she is containing and commanding the night sky within the four neat edges of the canvas too. “I like big spaces,” she said in 2019, “and I wrestle them into a small area and say, ‘Lie down and stay there, like a good dog.’”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.