“It felt like magic.” Joshua Vermillion was describing the first time he used artificial intelligence, or AI, to make an image.

Vermillion is an architect and designer who teaches at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He creates artwork of otherworldly spaces. Before he started using AI to do this, Vermillion would make maybe 10 pieces in a year. Last year, though, he made around 150 works. “I can just simply tell the computer what I want in plain English,” he says. “What a time to be alive!”

Many other artists, though, aren’t so thrilled about AI-generated art. Katria Raden is an independent illustrator and author based in Belgrade, Serbia and Berlin, Germany. People used to hire her regularly to create art for marketing materials or to illustrate children’s books. Last year, almost no one reached out about these types of jobs. The rise of AI may help explain this. “At times I think it’s a bad dream,” she says. “I feel scared and angry, but also pretty sad.”

Using AI to create an image is quick and easy. Popular image generators include Dall-E 3, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion. They are cheap or even free to use. They also pose threats to some artists’ jobs.

But the problems go deeper than that. To train an AI model to produce images, developers need to show it a huge number of example images. Such a library of examples is called a data set. OpenAI, the creator of Dall-E 3, has kept its training data secret. But the company Stability.AI, which makes Stable Diffusion, shared its data set. It contains 2.3 billion images tagged with text. Midjourney reportedly used this same training data.

These images were scraped from the internet. Data scraping automatically pulls files from webpages. Often, no one asks permission or checks what these files contain. Thousands of artists’ names and works have been found in the data set. Illegal or harmful images and people’s personal photos are also among those data.

Raden doesn’t like the way AI image generators were trained or how they’re being used. “It’s cheating and it’s basically fraud,” she says. Many artists agree with her. Their rallying cry on social media is “create, don’t scrape.”

Vermillion sees their point. But for him, the rise of AI tools has been mostly positive. At design workshops he runs, he always asks people how they use AI in their work. He recalls one participant saying, “Sometimes I just need a creative partner that doesn’t think like I do.” AI, he feels, can play that role.

AI image generators are getting more powerful. Some can now produce video. And they’re easier than ever for more people to access. In the past, new forms of technology have led to new types of art. Can AI boost human creativity and storytelling? Or might it exploit and overshadow both?

Catching copycats

AI image generators are supposed to produce brand-new pictures that don’t belong to anybody. Yet they can mimic or even reproduce images from their training data. In 2022, one of the most popular prompts on Stable Diffusion was a name: Greg Rutkowski. He’s a Polish artist who paints dramatic fantasy scenes, often with wizards and dragons. Stable Diffusion allowed people to make new images in his style.

In the United States, copyright laws protect creators’ ownership of creative works, including art, books, movies and popular characters. Using or copying someone else’s creative work without their permission isn’t allowed. So Rutkowski and a group of artists filed a lawsuit claiming that AI companies violated their copyright. Many similar lawsuits are ongoing as well.

Reid Southen is an artist based in Detroit, Mich. He works on concept art for major movies, including The Hunger Games and Blue Beetle. His job is to design sets and illustrate key moments in a movie. Then the rest of the team works toward capturing that image on film.

Southen isn’t involved in any lawsuit. But, he says, “I do know that my work is in the [training] data set.” And if you’ve ever uploaded a photo online, he says, “there’s a good chance that your image may have ended up in one of these models or data sets.”

That bothers him a lot.

Once, many years ago, Southen says, he took a trip to the Comic-Con convention with friends. “We had our car broken into and all our stuff stolen,” he says. They had to drive more than two hours back home on a cold night with a broken window. What’s happening now with AI image generators feels similar to him. “It’s someone taking your stuff,” he says. “It feels wrong, and there’s nothing you can really do about it.”

Southen may feel powerless, but he’s making his voice heard. He partnered with AI expert Gary Marcus to run some experiments in Midjourney and Dall-E 3.

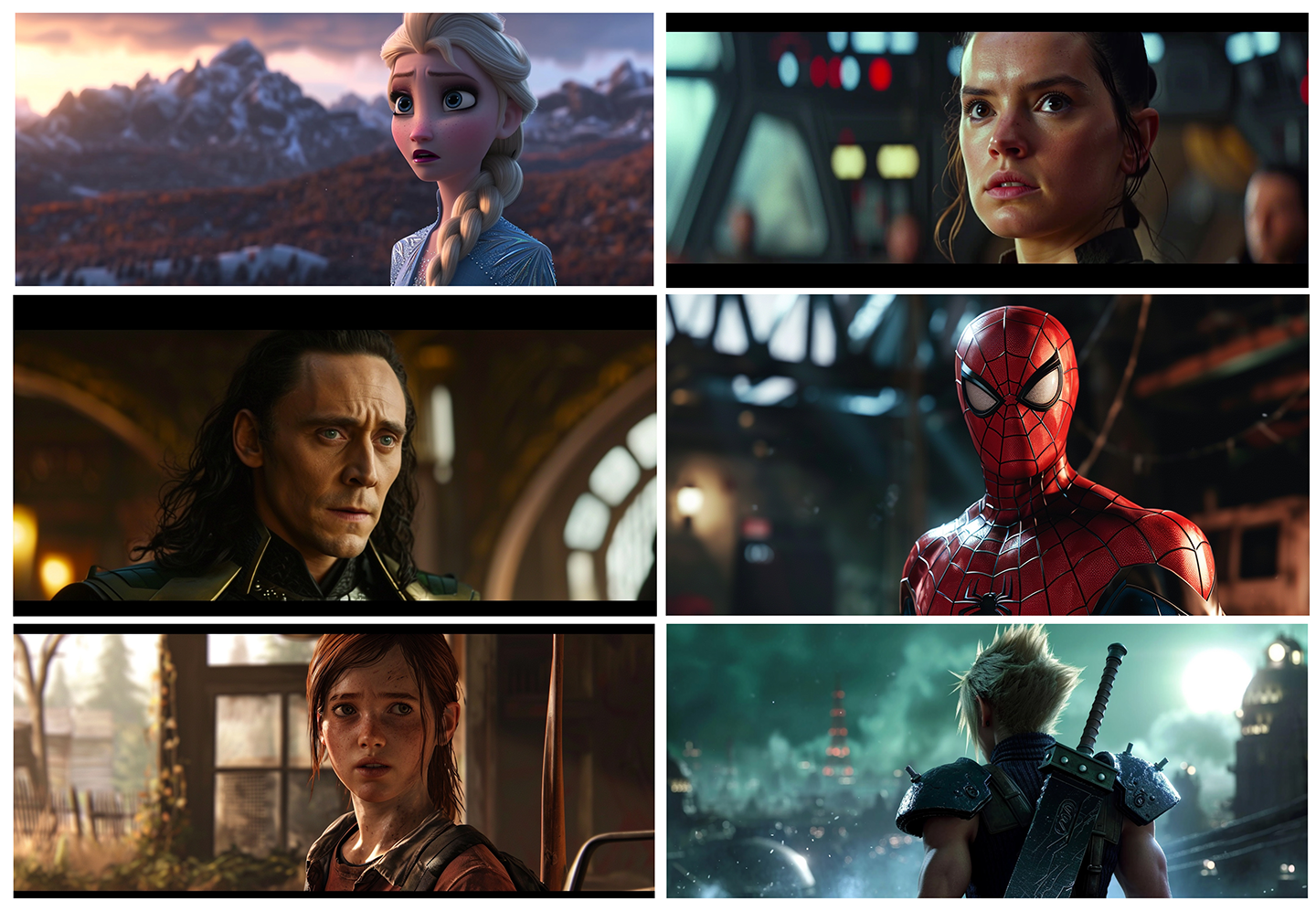

They got these AI models to spit out copies of screenshots and characters from existing movies and video games. They used short, vague prompts. The single word “screencap” led to a variety of copyrighted content, says Southen. “You get Spider-Man … Elsa from Frozen … video games, too.” The pair described their findings in IEEE Spectrum in January 2024.

The goal of their work was to point out that AI image generators will easily reproduce copyrighted content. The user doesn’t even have to ask directly for it.

Rewriting laws

Midjourney’s terms of service say that users may not use the tool to violate copyright. To Southen, putting this responsibility on users doesn’t seem fair. His research shows that users may accidentally get copycat content without knowing.

As it stands, breaking this rule can get a user’s Midjourney account shut down. This penalty happened to Southen three times while generating screenshots for his research. Each time, he paid for a new account so he could continue testing.

Southen says Midjourney’s data set must contain the images it manages to copy. “They don’t have permission to use that data.” This is the same thing that angers Raden and many other artists. Before feeding her work to an AI model, Raden says, “they should be required to ask me.”

People are generally allowed to use others’ copyrighted work without asking if they aren’t directly making money from it. They can use it for inspiration, research or analysis. For example, art students often copy other painters in their classes. And search engines like Google display links to copyrighted material in their results.

Joshua Vermillion created this odd creature with Midjourney. Art, he believes, “always requires a human touch and critical thinking.” When people use AI to generate images, they should consider context, cultural awareness, ethics and empathy, he says.

AI companies have argued that training AI technology on copyrighted images is a similar type of use. They don’t think they should have to ask permission or pay copyright owners. If the courts decide that they do, “I think we will see a slowdown in training AI in the U.S.,” said Amir Ghavi, implying that such a change could hinder innovation and progress. Ghavi was speaking at a May 2024 conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. He’s a lawyer who represents Stability.AI and many other AI companies.

Image-generating AI did not exist when copyright laws were written. So governments and courts will have to decide who’s right and who’s wrong here. Japan’s legal system has (for now) sided with the AI companies. In the United States, those legal battles are ongoing.

It’s not just AI-generated images on trial. AI-generated articles, books, videos, voices and more are triggering controversy, too. During the summer of 2023, Hollywood screenwriters went on strike. They managed to get their industry to agree to a set of rules limiting how AI may be used in the creative-writing process.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Cloaks and poison

Until new laws and rules get written, some people are taking matters into their own hands to protect human-made artwork from AI copycats.

Ben Y. Zhao led a team of computer scientists who worked closely with artists to develop a tool called Glaze. It can “protect individual artists against people who want to train a model to mimic them,” says Zhao. He is a professor at the University of Chicago in Illinois. Artists feed their original images through the tool and get back “glazed” copies to post online.

Glaze is like a disguise that fools AI models. It “confuses them when they try to train,” explains Shawn Shan. He’s a PhD student who worked on the tool in Zhao’s lab.

When image-generating AI is training, it sorts pictures into a many-dimensional map. That’s called a feature space. This map groups pictures with similar elements or styles closer together. The AI model later uses this map as a guide to generate new images.

Glaze tricks an AI model into placing an image in the wrong place on the map. It alters the pixels of an image so it looks almost exactly the same to a human. But to an AI model, it seems to have an entirely different style.

Glaze is free for artists. In its first year, says Zhao, it was downloaded 2.3 million times.

Glaze helps artists defend their unique styles. But “it doesn’t do much to solve the bigger problem,” he says. It doesn’t stop AI companies from grabbing files without regard for ownership or copyright. So the team made another tool, called Nightshade.

Zhao describes it as “a poison pill.”

Nightshade doesn’t just misplace things on an AI model’s feature map. It scrambles the map itself. For example, Nightshade alters images of cars to make them all seem (to an AI model) like one very specific cow. They still look like cars to people.

“Once a model has seen enough of this,” says Zhao, “they will be convinced that a car really does have four legs and a tail and a big white head with a nose.” Nightshade also makes dogs seem like cats, hats seem like cakes and so on. It mixes up styles as well as objects.

Zhao, Shan and their team discovered that adding just 100 “poisoned” images of a concept to a set of 10,000 normal examples can mess up the AI model’s training. And things got really wild when they poisoned hundreds of different concepts at once. In one test, they poisoned 250 different concepts with 100 altered images each.

This “breaks down” the structure of the AI model, Zhao says. Afterwards, even if you ask for a concept that wasn’t poisoned, all you get is “random gibberish,” he says.

Raden already uses Glaze and is excited about Nightshade, which came out in February 2024. In the future, she says, “I will use it on all of my pieces for sure.”

Imagining a future for AI in art

Raden hopes that Nightshade will teach AI companies to ask permission before grabbing images. What if they take in poisoned data and their tool breaks? “Serves them right,” she says.

Zhao sees no value in AI generators of any kind. The only real impact he sees is that quality work has become harder to find. “On the internet, in e-book stores, on sound streams, anywhere that there is content, it is now being filled with trash,” he says. Why? “Because it is so cheap to produce trash.”

Southen worries that art will suffer from a loss of human talent. “It just scares me,” he says. “If things keep going this way, brand-new artists who might have a lot of really awesome or important things to say are just not going to do it.”

To him, the best way to fix the situation is to start over. “Scrap the data set,” he says. “Kill the models.”

But not everyone feels this way about AI’s place in creative work. Some feel that creators will adjust and grow with AI just as they have with other new tech in the past. When photography was invented, some sketch artists and portrait painters lost work. But the new medium also led to new types of art. Vermillion notes that cameras “freed up” artists to try new forms of expression.

Southen doesn’t buy this argument. “Photographers didn’t steal from artists to make the technology work,” he explains.

Vermilion accepts that there are serious issues with image-generation AI that need to be worked out. He’s glad artists are making their voices heard. “We need to enter the fray, use the tools, experiment with them and be critical of them,” he says.

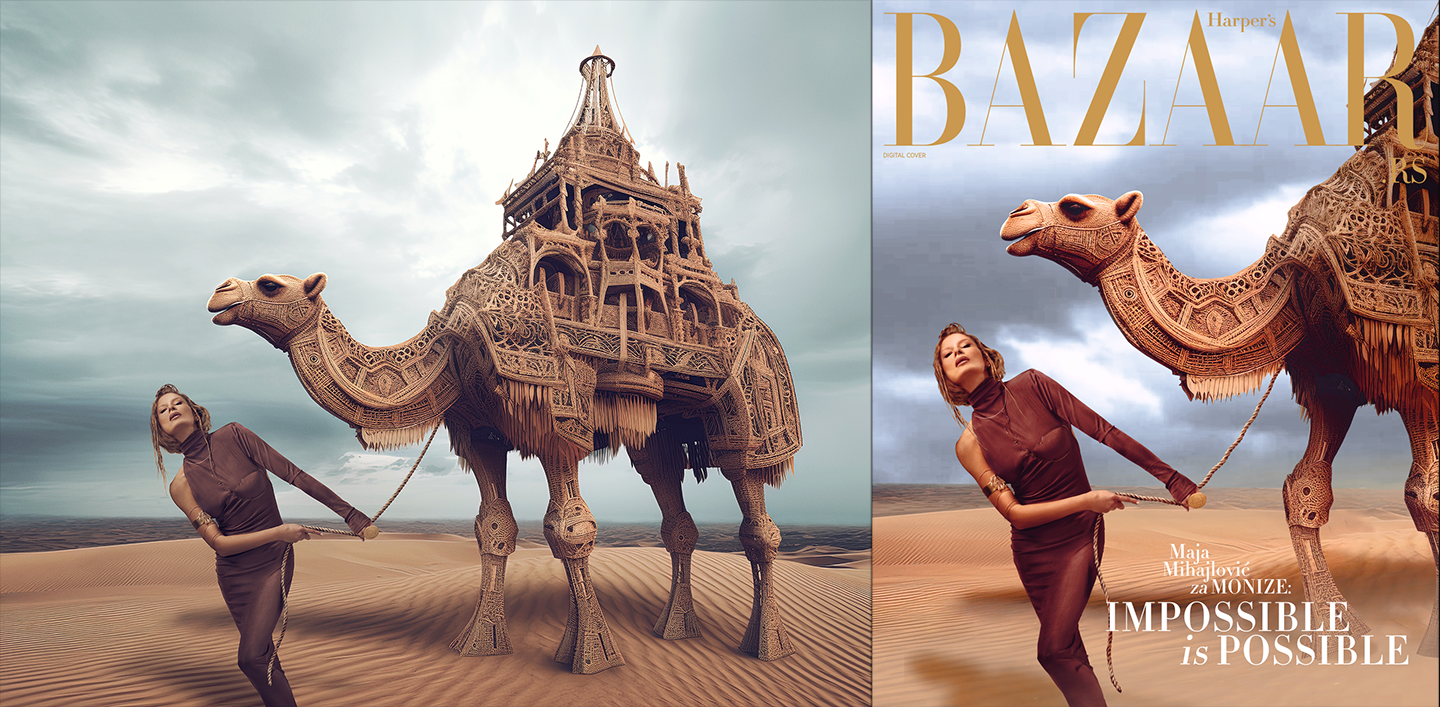

But in his experience, AI is already making possible new types of creative work. Vermillion worked with Harper’s BAZAAR magazine to do a shoot with real models and clothing but AI-generated landscapes and settings. He says they needed to involve more people than usual in the project, not fewer. “Everything I’ve worked on has not displaced any human labor,” he says.

Vermillion is also excited about AI’s potential to help build a metaverse of virtual-reality experiences. He’s experimenting with AI tools to fill in hidden parts of his flat images and turn them into spaces in virtual reality.

Which of these AI-generated places would you most want to visit? Architect Joshua Vermillion created these using Midjourney. He’s working on ways to turn such images into virtual-reality experiences.

He also appreciates that AI can stoke his imagination. “I want to be surprised by the results,” he says.

Many other artists are finding interesting ways to incorporate AI into their work. Sondra Perry, an artist based in New Jersey, uses AI-generated images and video. Agnieszka Pilat, a Polish-American artist based in San Francisco, Calif., works with robots to create art. She sees them as “collaborators.”

AI can help artists be more productive or make new types of art. It also opens up the world of visual expression to people who don’t have art skills or who can’t afford to hire artists. Are these benefits worth all the downsides? That’s up to us as a society to decide.

Some are already finding better ways to build AI models. The company Adobe released an AI tool called Firefly in 2023. Adobe made sure they had permission to use all the images in the data set they used for training. Firefly also applies labels to generated images noting that they are made by AI.

Explains Jingwan (Cynthia) Lu, a researcher at Adobe, the company realized it needed to “create responsible AI.” She spoke in May at the MIT conference.

To Raden, art is a way to connect with other humans and to share experiences. When she finds out an image was AI-generated, it feels similar to finding out an athlete cheated. “I do not want to enjoy generated content,” she says. “I want art.”