Lola Flash, “Clit Club Series,” c.1989-90, color c-print, 9 ¾” x 7”. Courtesy the ART+Positive Archives, collection of Dr. Daniel S. Berger/Photo: Lola Flash and ART+Positive Archives

A couple of weeks ago, as part of a panel discussion on women’s video cultures and the history of the Guerrilla Television movement hosted by the Chicago-based Media Burn Archive, Tracy Fitz and Barbara Jabaily, two of the founding members of the LoveTapesCollective (L.O.V.E. in the name standing for Lesbians Organized for Video Experience) reflected on their activities in the 1970s. As they described their interest in using video to record lesbian/feminist activities in the 1970s, the two emphasized how exciting and important it was simply to be able to see other lesbians. It’s hard to imagine that now: How radical it was at the time for lesbians, or trans or queer people, simply to be able to see people like them.

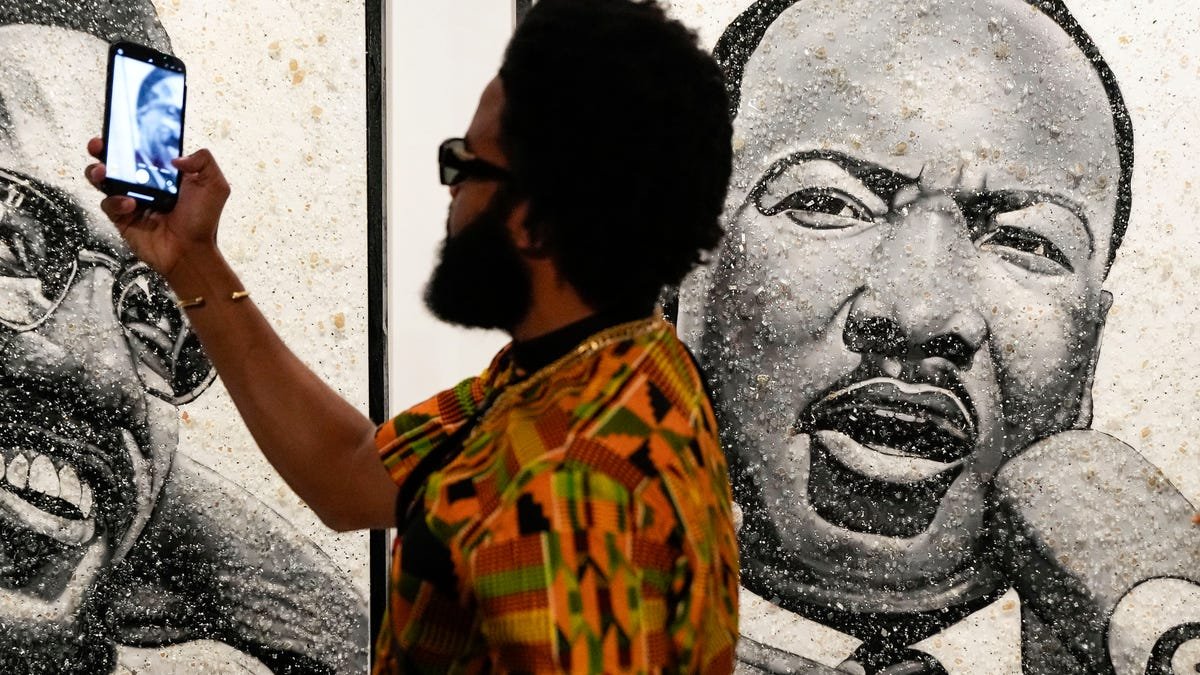

“Images on Which to Build, 1970s–1990s,” an exhibition currently on view at the Chicago Cultural Center, presents a range of feminist, trans and queer image-making practices that attest to that power but, as the exhibition curator Ariel Goldberg notes in the exhibition text, the image cultures under question went beyond “beyond the visual,” to create space “where felt experiences of affirmation, recognition and connection” too, could be forged.

Installation view of work by Joan E. Biren, in “Images on Which to Build, 1970s–1990s,” at the Chicago Cultural Center, 2024/Photo: Nathan Keay

Such a result is palpable in the exhibition. Featuring work from nearly thirty artists, collectives and archives, the show offers both eulogies and celebrations of queer life, and serves as just a small taste of how artists and activists expanded the subjects of photography in the 1970s and eighties while creating alternative models for presenting art and ideas.

The show begins with the work of Lola Flash and features numerous images Flash made using an experimental color-reversal printing technique that resulted in intoxicating, impossible colors and, notably, resulted in the impossibility of determining the race of her subjects. Like many of the artists whose work is on view in the galleries, her practice embodies the inextricable relationship between queer and feminist organizing and other efforts ranging from Black Power to the labor movements of the twentieth century.

Flash’s work shares a gallery with a video presentation of “The Dyke Show,” a traveling slideshow presented here as digital video with sound, in which the artist Joan E. Biren (or JEB) lovingly, and sometimes comically, related the history of lesbians over a series of photographs.

Stephen Barker, “Electric Blanket: AIDS Projection Project,” photo of “Funeral March,” November 2, 1992. The ninth photo in a series of twenty-five images of the election eve political funeral of ACT UP member Mark Fisher (1953-1992) [In the foreground: Joy Episalla]/Photo: Stephen Barker

Slideshows and other alternative modes of exhibiting images were an important tool for queer and minority communities in the 1970s and eighties; just think of Nan Goldin’s landmark work “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.” Another slideshow Goldin worked on, “Electric Blanket: AIDS Projection Project” and some documentation of its presentation at various locations in the United States, is on view here. Electric Blanket was a work of public art as well as a tool for education and advocacy that mixed portraits of individuals who passed from AIDS and those living with it, with statistics and information on the disease. Created by Goldin along with Allen Frame and Frank Franca the show toured nationally and internationally for over a decade beginning in 1990.

Grassroots organizers and artists did not just rely on slideshows though; newsletters and mail networks were also critical sources of documentation and information for queer communities. Correspondence between trans individuals on view in the show documents the impact of being exposed to information and images such as those Allen Berube presented in a lecture and slideshow in San Francisco in the 1970s in which he related the histories of three women who lived as men at the turn of the twentieth century.

Diana Solís, Women Free Women in Prison, March on Washington, 1979, archival Piezography Print, 16″ x 20”/Photo: Diana Solís

“Images” is heavy on archival material: newsletters, press clippings and excerpts from historically important literature such as Leslie Feinberg’s “Transgender Warriors,” share space with photographs of women and queer people doing the work but also, as in some poignant examples by the Chicago-based photographer Diana Solís, simply being together. The exhibition also includes a re-creation, of sorts, of an exhibition presented in 1991 by the NYC-based Lesbian Herstory Archives. “Keepin’ On: Images of African American Lesbians” was an exhibition co-curated by Herstory Archives members Georgia Brooks, Paula Grant and Morgan Gwenwald celebrating the strength and beauty of the African American lesbian community. In its “re-presentation” at the Chicago Cultural Center, the photographs demonstrate their age and history of use, pinned to aging poster board, their typewritten captions describing the individuals sharing a gaze with contemporary viewers.

The show is by no means exhaustive. It might be best experienced, as the exhibition title suggests, as a prompt to build on, inspiring viewers to pursue further engagement with the history, artists and organizations documented here. Despite what can occasionally feel like too brief a sketch of an organization or artist, Goldberg’s assertion that the work of these artists and activists is not just about representation but about shared feeling and connection is palpable in the ground-floor galleries of the Cultural Center. The affect generated by the exhibition’s often casual accumulation of ephemera and images serves as a reminder of what many of the letters and statements present in the exhibition attest to: the power of (merely) sharing space.

“Images on Which to Build, 1970s–1990s” is on view at the Cultural Center, 78 East Washington, through August 4.