Louise Giovanelli, the It-girl of British art, arrives at White Cube Hong Kong.

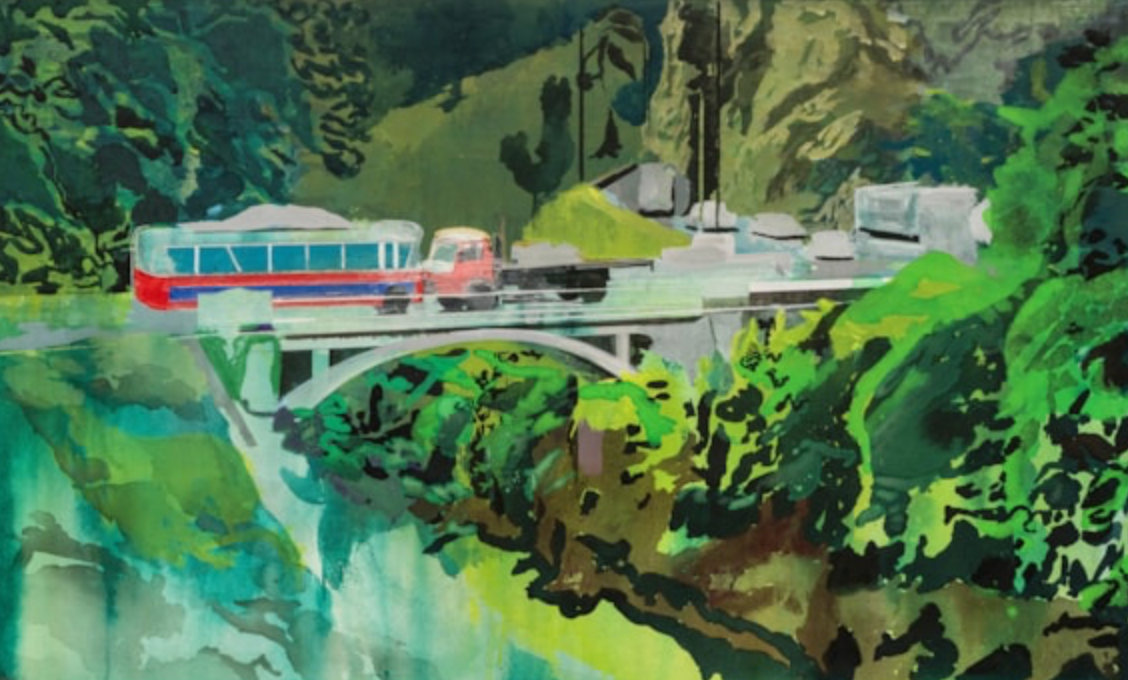

There are two types of people in this world. Those who first got to know Chinese director Wong Kar-wai having seen In the Mood For Love, or first became acquainted with Welsh-Italian artist Louise Giovanelli at the London Hayward Gallery’s Mixing It Up exhibition in 2021, on account of her expansive, lustrous green curtains. But flip that same coin, and the other type will tell you that Days of Being Wild is Wong’s best film (it was his first and featured an array of new talent – Maggie Cheung, Leslie Chung and Tony Leung, on the cusp of their collective cinematic moment), and that Giovanelli’s work circa 2017/18, three years before the curtain, had hypercontemporary tendencies in a post-Georgia O’Keeffe style. Both opinions are valid, but such matters become touchstones on the culture.

Louise Giovanelli is very much one of the It-girls of the current London art scene. Katy Hessel, author of The Story of Art (Without Men), says she’s “absolutely enthralled by Louise Giovanelli’s art”, and two days before I meet Giovanelli in her studio, Hans Ulrich Obrist, supreme curator of the Serpentine Galleries and his chief executive Bettina Korek visited Giovanelli in her sinfully cool studio in Manchester, housed in a disused tram depot. She’d been told of his pending arrival and tipped off that he’d ask his customary question of the artists he meets: what’s your greatest unrealised project? She’s not sure what exactly was at stake, but watch this space.

And as recently as December, when French luxury colossus Chanel went to Manchester to stage its annual Métiers d’art haute couture fashion parade, it enlisted poet John Cooper Clarke to read to Chanel VIPs in the basement of the very hipster Ol Peste Detroyed bar and vintage book and record store, formerly an undertaker’s office, on Oldham Street. As the likes of Tilda Swinton and Gwei Lunmei listened to the reading, their eyes could simultaneously admire the rapturous works of Giovanelli hanging on the walls. Indeed, had Wong Kar-wai ever ventured Manchesterwards, you can guarantee his iconoclasts would have brought their qipaos, cigarettes and neon to Ol Peste.

“Obviously film has always been a big influence on my work and Wong Kar-wai’s one of my favourite film directors,” Giovanelli tells me in her studio, ahead of her show at White Cube Hong Kong later this month. “His work’s just magnificent; everything’s slow, everything’s colour and light, and mood and psychological and every still is like a painting. He obviously considers the surface of the film much like a painting, really, and that’s also what’s made me want to visit Hong Kong.”

Giovanelli attended Frieze Seoul last year, but this is her inaugural Hong Kong trip. Over 10 days, she’ll have various collector and client interactions in the city, take a day trip to scope out Tank Shanghai (where she’s showing in 2025), and have three or four days to absorb Hong Kong. On which point, she has a query: “Are there any districts where you can have that feeling of a slightly seedy atmosphere?” she asks. “I’m basically looking for more curtains … yeah, and trying to weave in a research project while I’m there.”

Curtains and Giovanelli are a thing. And it was her work Prairie that first drew White Cube’s gaze her way when it wowed punters at the Hayward. Semi-abstracted, theatrically lit and with sumptuous tactility, the curtains are a vehicle through which Giovanelli explores the formal possibilities of colour meeting light in meeting texture, and indicative of the narrative ambiguity she strives for in her work. She explains: “These curtains, once thrown back, offer this promise to enter another realm – and once closed, contain that promise. The painting hangs in a suspended state, leaving us wondering whether the show is over,

or in fact, just beginning.”

She’s produced a curtain for the Hong Kong show, but this one, unlike the luxuriant Prairie, is faded, Sunset Boulevarded, tainted somehow. It’s like a less lustrous David Lynch, or unpeopled Alex Prager, and its sagging green/yellow folds pantomime with the limelight of times past. As we stand before it in her studio, I think of Stanley Kwan’s Centre Stage, the Yau Ma Tei district in the days of a younger Chow Yun-fat and, for reasons not entirely apparent but especially poignant, the Mandarin Oriental hotel and Leslie Chung.

Giovanelli doesn’t care much for storytelling, visual or filmic, of the direct variety. “I’m always interested in films that don’t really have a linear narrative, where narrative is like a secondary thing, and I’ll happily watch a film and not have an idea of what’s going on, and I’ll just appreciate the colour, or the formal qualities of it. That’s what I’m most interested in,” she says. Which sounds a lot like her paintings too. “I don’t really like overly narrative paintings either; nothing too descriptive or too obvious as an interpretation. Once a painting is too obvious or direct, then it just becomes a picture, not a painting.”

As such, she’s become associated with cropping techniques, which she says she treated like a learning device or magnifying glass while studying at the Manchester Metropolitan University’s School of Art. “I’d take snapshots out of much bigger Renaissance or Flemish paintings and make a painting out of those.” Her crop is so tight that the majority of her works show no background or foreground detail, and the act of looking in a Giovanelli painting thus becomes itself a kind of content.

She’s also become associated with large-scale meditative paintings that capture ephemeral or sensual moments, concocted using beautifully crafted textures and beguiling colours. She typically uses film stills, classical sculptures, staged photographs and architectural elements, and features fabric and locks of hair. The results are generally captivating, luminescent experiences as paintings, which by turns conjure rapture, ecstasy, worship, joyfulness and ethereality, but always ambiguity. When a laugh becomes a scream, or what sort of rapture she’s proposing aren’t self-evident. “A painting should be the beginning of something,” she says. “The best paintings are those that endure in your mind, because there’s this sense of mystery to them.”

Coincidentally, Giovanelli had just seen the work of Liu Ye at David Zwirner in London, in which the artist had shown a group of paintings depicting Maggie Cheung in Wong’s In the Mood for Love. Liu used film stills as his source material. How did she “read” those paintings? “The portraits were beautiful and gorgeous,” she affirms, “but I wouldn’t have chosen something so obvious. There was one where you see Maggie Cheung walking up the stairs from behind and you see her hourglass figure – that’s what I mean about overly descriptive paintings. I would have preferred a bit more mystery.”

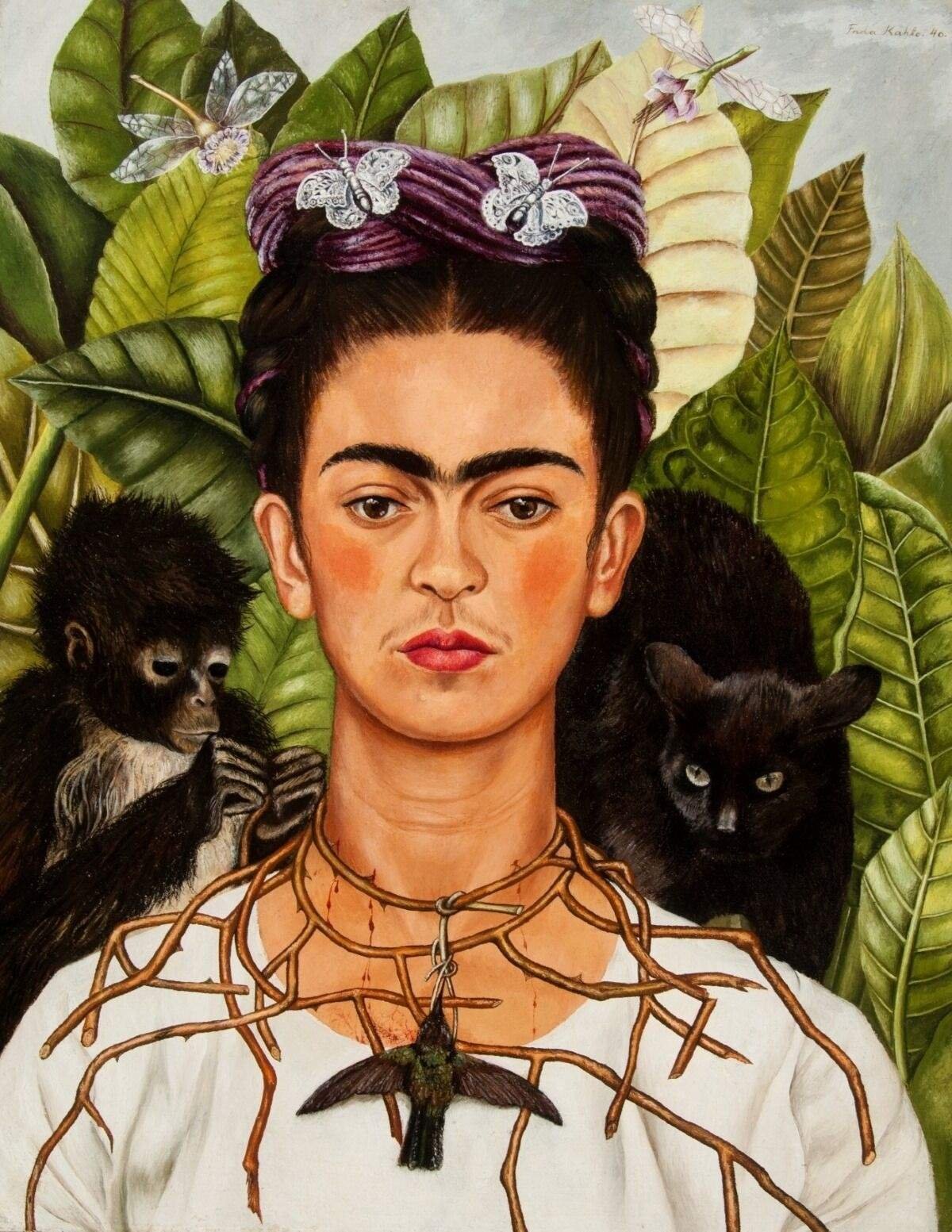

In recent work – and her show in Hong Kong, not all of which was finished when we spoke – Giovanelli has been continuing to explore what she calls modes of devotion and worship. “As humans we’ve directed our attention and behaviour towards these instances of visual light phenomena, and I think the same happens in celebrity culture, and social media and lights on your phone. And it’s all the same, the same intuition. So I do think there’s been a transference from the idols, the icons and stained-glass windows of the designated sacred buildings of the past, and we don’t realise we’re participants, but we are the more you think about it.

As such, she has painted several images with prominent faces, one of which is titled Maenad. “That’s what I’ve been thinking about; Greek mystery, rituals that used to go on, and how there were all these females at the centre of these ceremonies. It sits very well with this imagery.” Half the work she’s produced for the White Cube show she made while on a residency at Neuendorf House in Mallorca, Spain.

In the past she’s channelled Sissy Spacek and Mariah Carey in her work, and when I ask about the influence for Maenad, she says she wants to be more subtle. “There’s a direct reference, but I’m trying to be more secretive about my sources and references. I don’t think anyone would know who it is, and if they do, I’d be very impressed. It would be a private joke between me and them.” In a vivid POV moment, I tell her the dental work reminds me of a younger version of Chinese actress Shu Qi.

Giovanelli is nothing if not thorough and perfectionist. “The act of painting is like a thought process. It’s striving for perfection, how can I best create this image? Through Old Master paintings you learn to see in layers and that’s how you can manage to achieve the most luminous painting quality. It’s somewhat like striving in the face of impossibility, but I want my paintings to have a kind of universality.”

Fellow White Cube artist Julie Curtiss makes the following observation about her painterly peer. “Louise is cool. I visited her when she had a studio in Dumbo [Down under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass], Brooklyn, for a residency. When I saw the studio I was very impressed by her mastery, knowing now that she’s very inspired by Flemish painters makes sense to me. I remember what she said about her process, because it’s pretty much opposite to my painting process. While I focus on the line and work by addition, I remember Louise saying that she painted like a sculptor, by removing the paint and trying to reveal the light. I work with opacity and she works with elaborate layering.”

Giovanelli is a big fan of American artist Francesca Woodman who died when she was just 22. Woodman was known for photographing herself, often nude, in empty interiors, but not in traditional portrait style, more as half-hidden or obscured by slow exposures that blurred her figure into a ghostly presence. Her images are printed on a small scale, thereby seeming personal and intimate. Woodman, who admired the work of fashion photographers Guy Bourdin and Deborah Turbeville, could be read as the precursor and inspiration for Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin and Sophie Calle, who followed, and naturally, Giovanelli.

Given her schedule is so gung-ho, what is Giovanelli hoping to achieve in the short term, over and above her already much celebrated success? Tantalisingly, she mentions film. “I’d like to make a short art video or film. But it won’t be much before 2027.” Curtain up.

Louise Giovanelli: Here on Earth opens March 26 and runs through May 18, 2024 at White Cube Hong Kong.