“They say it’s gentleman racing but as soon as everyone’s on the track they’re all trying to kill each other.”

So he’s reverting to adolescence?

“You do, yes, the need for speed. It’s great fun, they’re beautiful historic cars, they’re works of art really in themselves.”

Fresh off the track, later this month, Langsford will head to the art fair, Frieze Los Angeles, then on to New York to meet with acclaimed Aotearoa artist Max Gimblett.

Gimblett, who is represented by Gow Langsford Gallery, has been commissioned to create four works in collaboration with Elysian Parnell, a luxury apartment project. Gimblett’s work will appear in the main lobby entrance and on each landing of the building that boasts views over the CBD and Waitematā to Rangitoto Island. The view, however, will be up against stiff competition from those bespoke canvases.

Langsford was first approached by the developers keen to make a statement.

“They initially came to see me and were looking for something for the lobby and we talked and we had a Max Gimblett commission. They saw that and that was the beginning. I thought well I’ll sell them a couple of things, but they wanted much more involvement. They wanted the apartment block to have that sense of quality and really focus around one major artist rather than put one thing in, and a whole lot of prints for example. So they’ve had a really interesting approach to it.

“As an art budget, compared to most apartment blocks, it’s significant.”

They are starting from the top of the market, says Langsford, “and they’ve made the right call.

“Max is obviously a significant artist in the twilight of his career. He’s one you would call a blue chip artist. That was why Max was perfect.

“That’s become a big focus of the building – so it’s the architecture and the art being at the right level. So it’s a gain. It’s a package of quality. It’s a unique partnership.”

It sounds like a legit pitch for an off-shoot of Grand Designs: “Masterpieces in Homes.”

“It’s a great way to see great art,” says Langsford. “If you go into most apartment buildings they have prints – some have art. But this focus on this is really unusual. I think it’s great for anyone who’s buying an apartment or building, or visiting. It’s exposure to a great New Zealand artist. It’s not in a gallery, it’s more personal, and it’s a different environment. An environment they live in or walk past.”

Langsford was in his 30s when he opened, with Gow, the gallery that would see him travel around the world – New York, Miami, LA, Tokyo, London – and become one of New Zealand’s leading dealers. He’s the hustler from Hamilton, a risk-taker, and a self-described optimist. “You have to be, to be a dealer.”

Before the racing driver was an art dealer (still is); before the dealer was an artist; and before the artist, a musician. And before all that, a boy from the hood with no life plan or specific ambition except to rage against the perils of “normal”.

“At 12 I didn’t have a plan but I was playing guitar. We lived in the roughest part of Hamilton. It taught me that you have to work. My dad worked two, sometimes three jobs. You learned a work ethic. He played about five instruments. He’d just sit down and play the piano. Mum was the arts inspiration, the visual arts influence.”

He wasn’t mentored at school in art; rather it was the absence of it that drove him into that realm. Like plants that thrive on deprivation.

“I went to Hamilton Boys College which was probably the worst place then in terms of the arts. It was maths, science and rugby. You couldn’t take French and art. Once I got UE and wanted to go back into the seventh form, they said, ‘we don’t have any courses. There’s nothing you can do.’

“So I applied for Elam [School of Fine Arts] and I got in. I think I was a bit of a wild card. They probably thought ‘we need someone from the provinces.’”

As a boy, he wouldn’t have even imagined that. “I guess growing up we always instilled in us there was something more – something outside of this.

“My other brother was a pro-tennis player and ended up coaching in Germany for 15 years.

“So yeah there was a sense of not doing the normal. I think then it was about ‘where’s the next big place I can go to from Hamilton?’ It’s Auckland and then it’s Melbourne, and London and it just sort of expanded from that.”

He funded his time at art school playing in covers bands in Auckland nightclubs and later, with DD Smash.

Gow Langsford is expanding again, this time to a vast warehouse in Onehunga. It’s a strategic and pragmatic move.

“It’s a bit of an international model – we have a small gallery in the city and a big gallery on the outskirts. Because you’re not going to get 2000 square metres in the city. Onehunga is halfway between the airport and the city. From where we’re sitting in Kitchener St it’s 15 minutes. Anywhere else in the world, you’d drive at least an hour to such a gallery. It’s a fantastic building. A lot of our people fly in and fly out. So that’s great.”

There’ll be an exhibition programme but it’ll be more museum-like in scale. “Installations, sculpture … we’ll have the gallery, artist studios, office space, an art library that people can use because there is no longer an art library in the city – the Elam library closed down. We’re putting in a restaurant downstairs so we can cater for events. It’s a big deal.”

Langsford, who studied sculpture, no longer makes art: “There are much better painters and sculptors than I am. I gave up doing the work when I discovered doing the deals.”

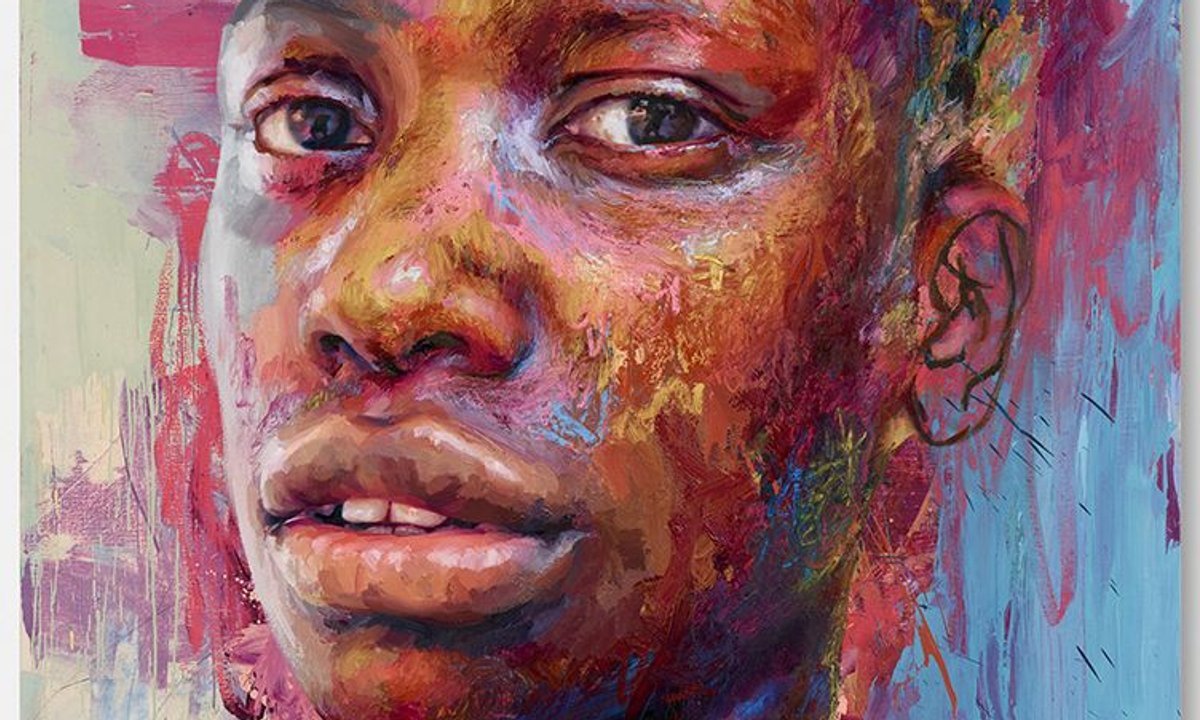

There are so many artists, too many, to select a favourite. But he cites Shane Cotton (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Rangi), back in the Gow Langsford fold, as singular in style.

“Shane occupies quite a unique space in New Zealand 20th-century art. Ralph Hotere was the senior contemporary Māori artist, and there are a number of Māori artists who have come through since but the thing with Shane is the paintings tell the story so well.

“They’re loaded with meaning and references. He’s been through a number of different styles but there is a certain aspect to the work that’s consistent, very narrative. Very of this place. You look at a Shane painting and you really can’t say it’s of Puerto Rico or some other place, you know? It’s really a New Zealand indigenous painting.”

Why do we need art? What does it give us, society?

“Visual arts should get you in ways you can’t verbalise. That extra dimension.

“I think it’s enriching your cultural soul and it’s not just great art, it’s great architecture, wine, food. A part of life. We can all live a very boring, grey life but where’s the fun in that?”

From his office in Kitchener St, dressed entirely in black and wearing Italian black loafers, Langsford appears to be the man who has it all. On the wall is the most spectacular Bill Hammond; there are several McCahons, a Frances Hodgkins and a Goldie. He doesn’t own a Banksy. “No, I had about three of them but they didn’t sell so I sent them back to the gallery.”

What do you give the man who has a car collection, a home in Matakana, a sprawling new venture and a contract with a luxury apartment developer?

There is one thing he covets. “I’d love a Lucio Fontana egg. When I first looked at them they were about $US800,000. Now, they’re about $30-35 million.

“Miuccia Prada owns about five.”

Gary Langsford’s tips for investing in art

- Decide where you want to invest based on your income. If you have lots of money, you’re probably looking at older artists. And that’s almost a guarantee.

- If you have less to invest, you want to take a punt on younger artists, and you get lucky, that can be fantastic. Like the Jean-Michel Basquiat that sold for $19,000 in 1986 and five years ago sold for $110 million. There are people here who bought McCahon in the late 70s-80s – big, hard-to-hang paintings for like, 20k and that subsequently sold for two to three million. It’s a compulsory form of saving and you get to enjoy it as well.

- The trick is to form a good relationship with a gallery, particularly one that’s been around for a long time. So you’re not chancing your arm on someone who won’t be there next week. Most people can go it alone – but there’s a huge risk in that.

- The first thing I bought was a Tony Fomison. It hung in my bedroom – it was fantastic. I got what I call a ‘dose of the shorts’ and had to sell it. I paid $7.5k for it and sold it for $15k. So that’s good. You know what it is now? About $600,000. I know exactly where it is and some years ago I offered him 200k and he said no. I couldn’t buy it now.