Can art be created by being unmade? That’s the question that led American Pop Artist Robert Rauschenberg to create one of his best-known and most controversial works, Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953)—a work on paper created by a taking a drawing by Abstract Expressionist legend Willem de Kooning and, as the title suggests, erasing almost all traces of it.

Rauschenberg came to the idea of erasing artworks via his series of “White Paintings” in the early 1950s, a set of all-white canvases in which the artist worked “with no image.” In a 1999 interview, he explained that “the only way” to create a drawing for the series was “with an eraser,” but he found that “when I just erased my own drawings, it wasn’t art yet.” He needed, then, to start with pre-existing art by another artist. He put his choice of de Kooning down to the fact that the Dutch-American painter was the “best-known acceptable American artist that could be indisputably considered art.”

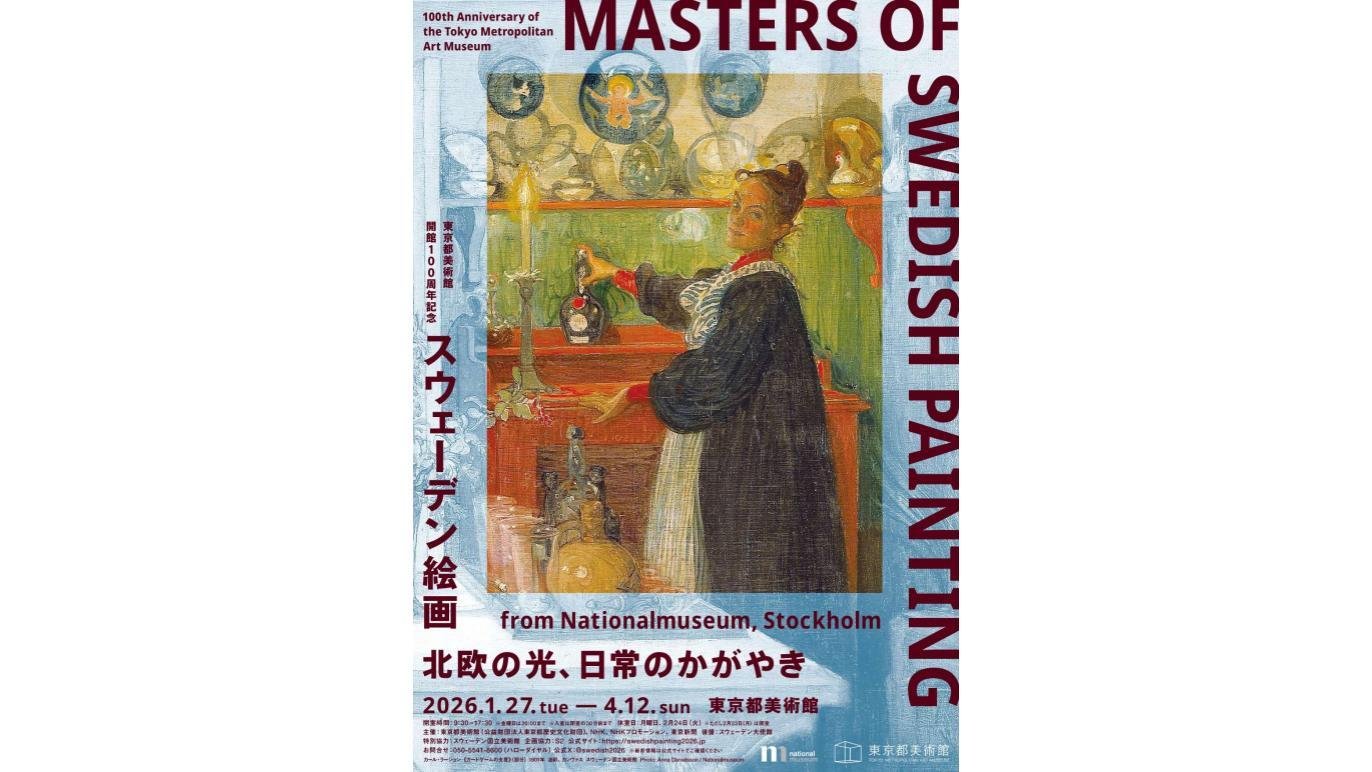

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953). Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

De Kooning was Rauschenberg’s senior by 21 years, and by the early 1950s he had a reputation that preceded him internationally thanks to his contributions to Abstract Expressionism’s “Action Painting” branch. In 1953, a 28-year-old Rauschenberg was newly back in New York. He had returned from traveling in Europe and North Africa, following his studies at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College and at the Art Students League of New York. It was at Black Mountain College that Rauschenberg and de Kooning had first met in 1952.

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning (1953). Courtesy of the National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design.

He won de Kooning over with a bottle of Jack Daniels as a gift, with the elder artist reluctantly agreeing to donate one of his drawings for Rauschenberg to erase. Rauschenberg recounted how de Kooning said, “okay, I don’t like it but I am going to go along with it because I understand the idea.”

De Kooning could have offered Rauschenberg a drawing that he didn’t think much of and was happy to part ways with, but he knew that that wasn’t what Rauschenberg’s gesture needed. He told the young artist that it would have to be “something that [he’d] miss.”

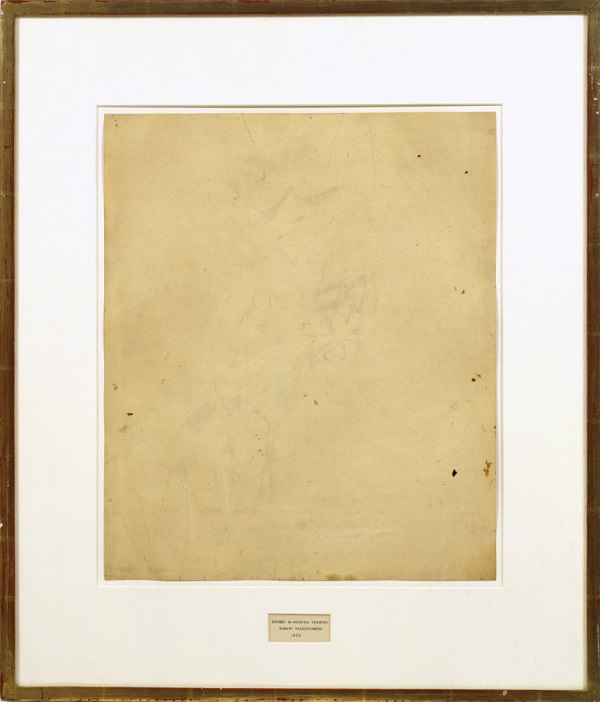

Digitally enhanced infrared scan of Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) showing traces of the original drawing by Willem de Kooning. Visible light scan: Ben Blackwell, 2010; Infrared scan and processing: Robin D. Myers, 2010. Courtesy of SFMOMA.

The erasing took Rauschenberg around a month to complete—so long that he lost count of how many erasers he wore down in the process, though the total was likely around 40.

Once the new work was finished and framed, an inscription was added by the painter and sculptor Jasper Johns, whose studio was upstairs. (Johns and Rauschenberg’s romantic relationship began that same year, lasting until 1961.) The simple gilded frame of the piece was designed to mimic those used in traditional art framing in academies and institutions. Both frame and inscription are very much an inextricable part of Erased de Kooning Drawing, suggested by the fact that the medium is listed as “traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame.”

Fascination with the artwork and de Kooning’s erased original has continued in the 70 years since its creation. The work was acquired by San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) in 1998, and twelve years later SFMOMA used infrared technology to scan the artwork and digitally enhance the image to reveal de Kooning’s original design. The original artwork appears to show several figures, rendered with charcoal and pencil. These scans are the only photographic evidence of de Kooning’s original work.

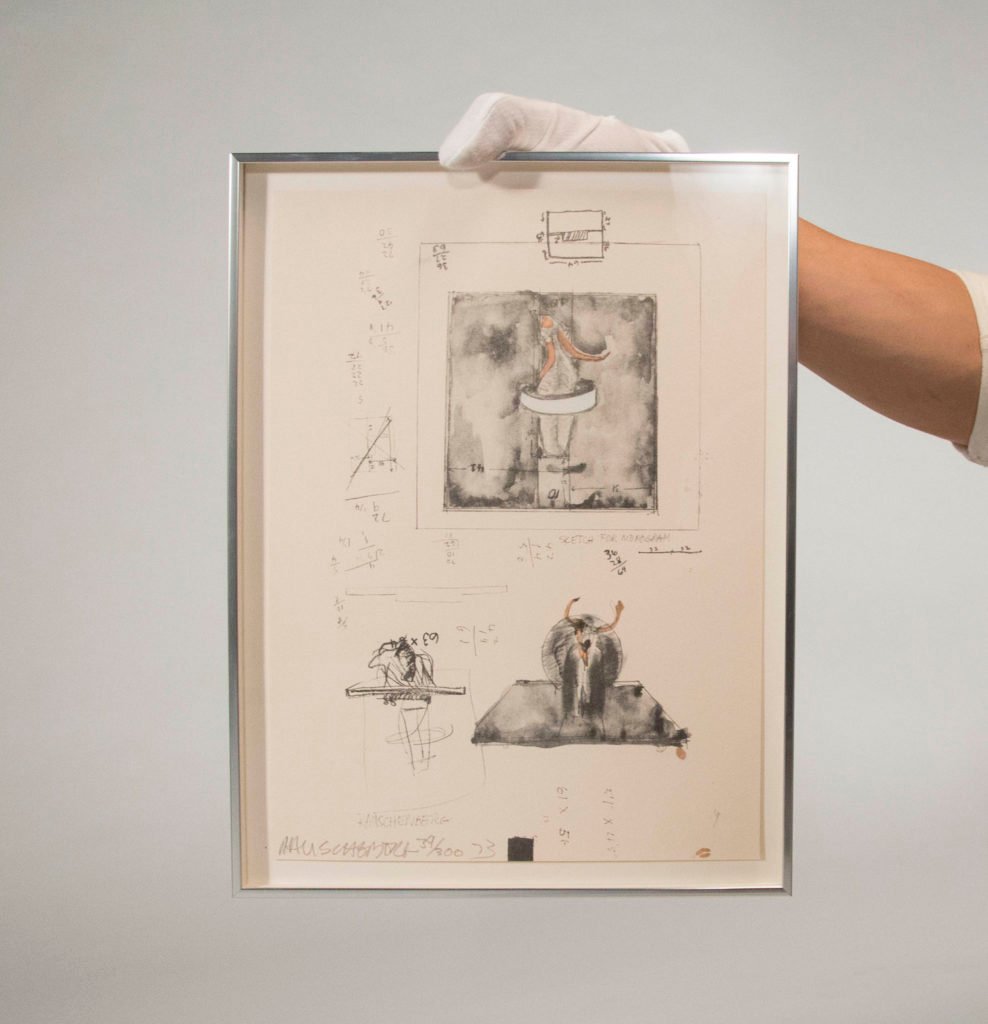

Nikolas Bentel has destroyed Robert Rauschenberg’s Untitled (1973) by selling advertising to cover the original print. Courtesy of Nikolas Bentel.

In 2018, artist Nikolas Bentel drew inspiration from Rauschenberg and enacted a sort of creative revenge: “erasing” Rauschenberg’s Untitled (1973). Rather than using erasers to transform de Kooning’s work, Bentel unmade Rauschenberg’s original print by selling advertising space to cover up the artwork inch by inch. To purchase Untitled (1973), Bentel had to raise $10,000. He did so by selling advertising space at $92.59 per square inch. Bentel’s stunt was designed to shine a light on the nature of the art market. “Since art market capitalism was once the force that created the artwork’s value, it will now be the force that will destroy the artwork,” he said.

Following its “erasure,” Bentel successfully sold the work for $21,000 at auction, twice its original value.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history.