The show, “At Variance,” featured a broad range of Tennis’ drawing, collage and painting. Building from a years-long practice of automatic drawing—tapping into the subconscious by drawing randomly across paper—the artist’s warm-up studies set the stage for his more complex paintings and collages. “I’ve noticed for years that while starting a drawing on a blank sheet of paper, I can feel opposing forces wanting to influence what happens, whether it’s abstraction vs. figuration or mechanical versus organic, or dynamic versus static, etc.,” Tennis says. “That tension feels a little like electricity, and sometimes I think that this subtle energy is helping to drive the drawing.”

Tennis, whose family moved to Seattle when he was 12, started creating art in high school. As an art student at the UW, he studied with Dailey and Mike Spafford, both celebrated among Northwest artists. Under their tutelage, he developed his work ethic. “I was in love with the idea that making art was work, kind of like a job, which added some much-needed weight to the art school experience. I kept that part,” he says.

He also independently studied with Professor Jacob Lawrence, who was internationally celebrated for his print series documenting the African American experience. “I was fooling around with these little Clyfford Still-influenced abstracts,” says Tennis. “So I’d come in and put them on the floor and the master of narrative painting would say, ‘OK, Tennis. See you next week.’

“If I was paying attention, I may have learned that art is made by people who live lives … and that I had very far to go in that regard,” Tennis says. “But the feeling in the room that I remember was one of respect on my part and more than a little patience on his.”

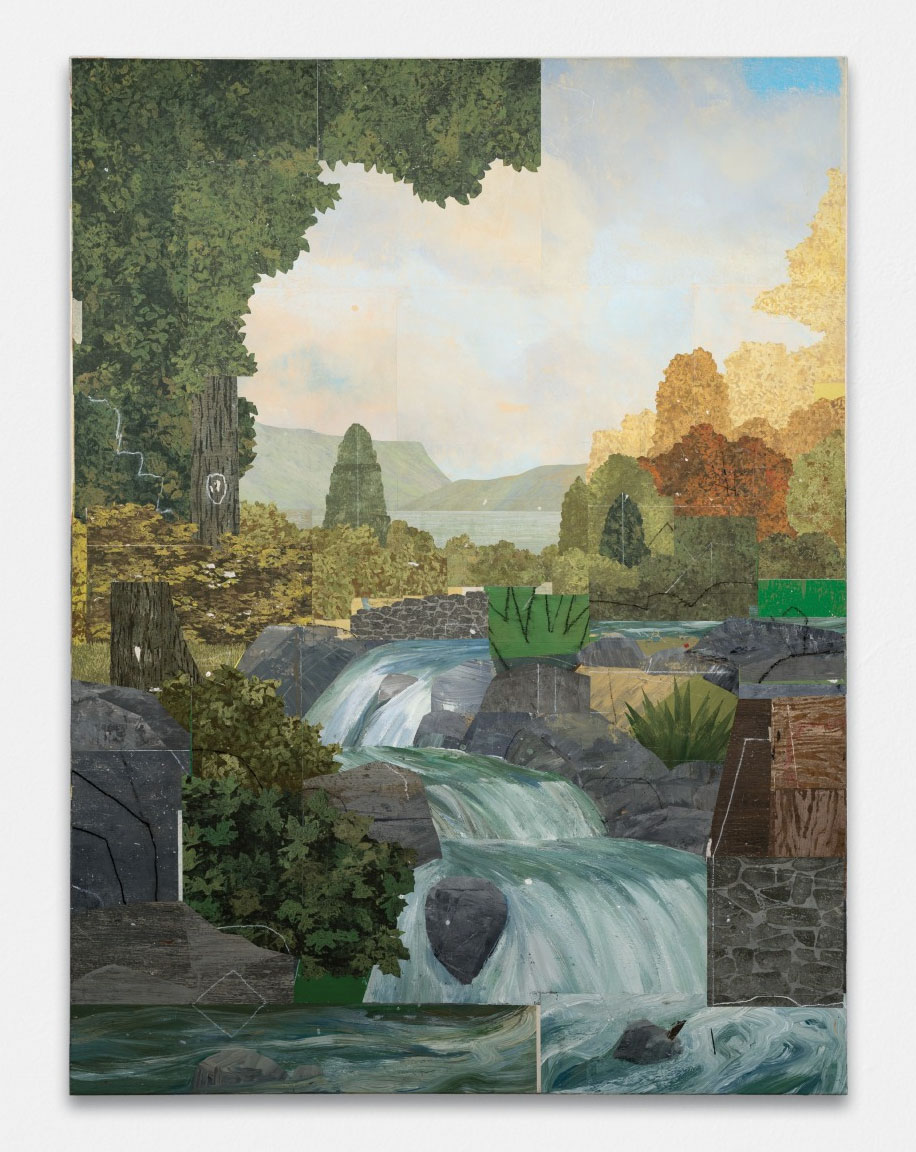

- “Hudson” by Whiting Tennis

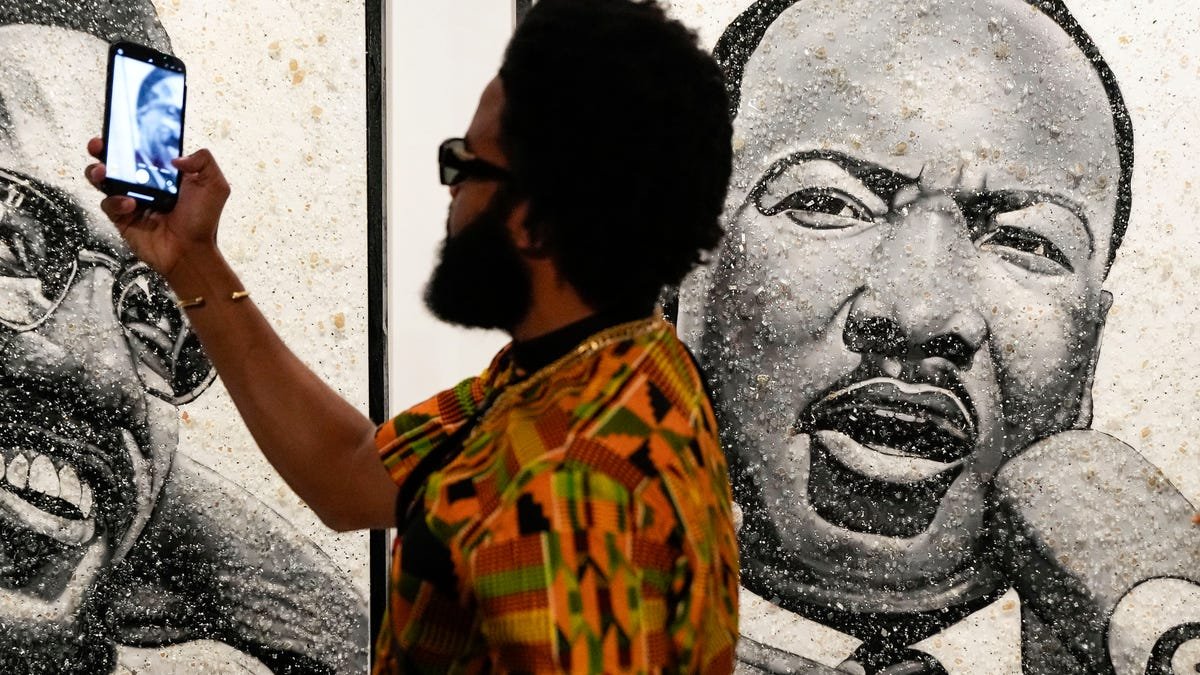

- Tennis in his studio

- “Study for Napoleon” by Whiting Tennis

After graduation, Tennis had some solo exhibitions in Seattle and Barcelona, Spain. In the 1990s and early 2000s, he lived in New York. A brief New York Times review of a gallery show there in 2001 noted, “Mr. Tennis neatly pieces together Cubist collage pictures of melancholy rural American scenes. The muted convergence of Modernist abstraction and pastoral nostalgia is unusual.” Back in the Northwest, his fan base was growing. In 2007, Tennis won the Neddy Award, followed by the Arlene Schnitzer Prize from the Portland Art Museum in 2008. His sculptural work has been commissioned by Vulcan, and he recently completed a painting commission for Gates Ventures’ office in Southern California.

Tennis’ recent exhibition in Portland included a dozen or so smaller drawings, plus a handful of larger paintings. “Hudson” combined his signature approach of blending painting, collage and printmaking—a practice he picked up at the UW while studying woodblock printing with Spafford. Based on a sentimental painting of a countryside that Tennis found in a thrift store, arboreal forms and flora compose a Romantic landscape reminiscent of the Hudson River School painters. But closer inspection reveals a complex trompe l’oeil. Seams in the piece indicate where hand-printed sections of the landscape have been collaged together. The acrylic-painted water elements flow across the canvas.

Another work, “White House,” expresses political undertones and clues the reader in to the artist’s ideology. “The piece started out as an all-over painting that was intended to be an abstract clash of painted and printed building surfaces,” Tennis says. But it moved toward “a picture, a place and finally a metaphor.” Embedded with numbers and clues, “1619,” the year that marks the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in North America, stands out.

“White House” by Whiting Tennis

Tennis shows regularly on both coasts. Back home in his Seattle studio, he’s laying the groundwork for his next solo exhibition for Greg Kucera Gallery in May 2025 while also working on a fourth album with his rock band. Also a popular singer and songwriter, Tennis performs around the Pacific Northwest. One side of his industrial studio is filled with painting supplies, drawings and sculptural models, while the other half is filled with recording equipment and electric guitars.