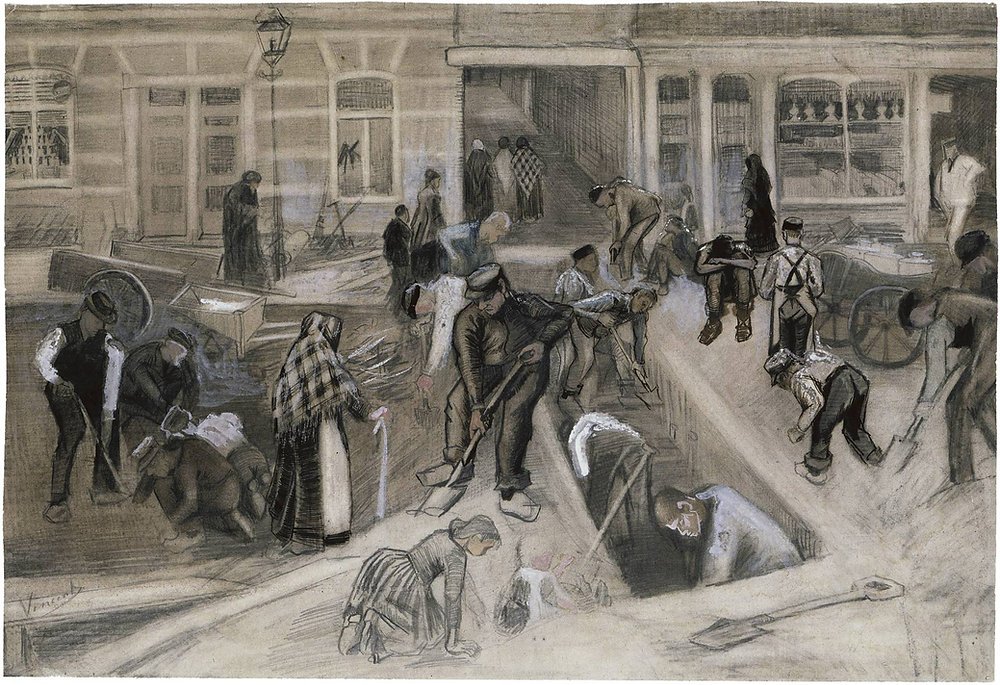

If you’re looking for a book about Vincent Van Gogh, then a new publication spotlighting some of the artist’s greatest works might surprise you. Because there’s hardly any paintings in its pages — it’s all about Van Gogh’s magnificent drawings.

People are much less familiar Vincent Van Gogh’s work on paper compared to his (admittedly incredible) artworks made with paint.

Yet Van Gogh was a prolific draughtsman. He produced over 1,000 works on paper, more than those he created on canvas.

So that’s why a new book is hoping to bring the artist’s stunning drawings into the light. (Metaphorically of course — we all know paper and light are not happy bedfellows in the museum world, as you’ll see below).

The Drawings of Vincent van Gogh — published by Thames & Hudson — has been written by art historian and curator Christopher Lloyd (who was also Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures in the Royal Collection from 1988 to 2005).

While there’s been some previous attention to Van Gogh’s drawings, his new authoritative overview breaks from the norm by taking a look at the artist’s drawings by theme: figures, landscape, portrait etc.

It’s resulted in a compelling and accessible record of the successes, failures, experiments, trials and disappointments of what Van Gogh committed to paper during his lifetime.

— Get the latest museum and exhibition news delivered to your inbox by subscribing to our free newsletter

It gives a greater understanding of why drawing is so important within Van Gogh’s unique oeuvre, and why it equals the intensity and reputation of his paintings.

So, for such a needle-moving new book that will no doubt be at the top many art-lover’s Christmas lists, I had to interview Christopher to find out more. Here we discuss personal favourites, the extensive damage these masterpieces have suffered, and the challenges of saying something new about an artist that’s been examined in so much depth already

The aim was to write an assessment of Van Gogh as a draughtsman for the general reader. His drawings have previously been included in the catalogues raisonnes, and exemplary catalogues of the main collections of Van Gogh’s drawings have also been published. Plus, informed exhibitions of the drawings have been organised over the years with accompanying catalogues of the highest quality.

But beyond these, the only previous general book discussing the drawings was published in 2005 where the material was arranged chronologically. My idea was to present the drawings thematically thereby demonstrating Van Gogh’s wide-range and deep commitment to his works on paper, which in turn would provide fresh insights that are not evident in his paintings.

His stylistic development was never straightforward and tended to veer in different directions at any time so that to treat the main topics thematically provided a more structured approach as well as a more comprehensive account of the subject which is easier — I hope — for the reader to follow.

Just how prolific in drawing was Van Gogh?

The number of drawings is extensive — certainly over 1000. These are usually signed and dated so that in essence they provide a visual diary of the artist’s working life between 1880-90.

Van Gogh also liberally illustrated his letters with sketches and used sketchbooks (although only a very few of these survive). Principally a landscape artist, his figure studies are spectacularly strong, particularly those of the rural poor with whom he so closely identified. Compositional drawings and portrait drawings are less numerous, but are nonetheless firmly executed.

Van Gogh’s eye was omniscient in the sense that he responded instinctively and creatively to his immediate surroundings and the people he met or knew. This applies as much to his work in the north in The Netherlands as to his subsequent experiences in Paris, Arles and Auvers-sur-Oise.

Do you think his drawings deserve to be as widely known and celebrated as his paintings?

Van Gogh’s drawings are as revealing as his paintings or his letters, each fulsomely illustrating his ambitions as an artist and his struggles as a man.

He decided to become an artist late in life when nearly 30 in 1880 having pursued other very different career paths. Essentially he was self-taught through the use of drawing manuals and saw his lack of formal training as a drawback almost to the point of developing an inferiority complex in this respect.

In fact, it was his self-sufficiency and his determination never to give up learning throughout his life that informs his art with its power and originality. This is seen in his paintings, but perhaps more so in his drawings many of which are experimental in the use of materials and techniques. The bursts of activity that punctuate his life alternate between separate periods of painting and drawing, which prove that in his eyes both share an equal autonomy.

What are some of your favourite Van Gogh drawings?

The studies of rural figures done while living with his parents at Nuenen (1883-85) are amongst the most powerful in European art.

Of the landscape drawings, those done in Brabant and those in the south of France while based in Arles are full of atmosphere (the debilitating damp of the north contrasting with the intense heat of the south), and have an overwhelming sense of place.

Of course, the vivid and forcefully executed drawings in mixed media showing the interior of the asylum at Saint-Remy are particularly moving redolent of the artist’s mental plight at that stage of his life.

Where can people see some of Van Gogh’s drawings — both in Britain and around the world?

The main collections of Van Gogh drawings are in the Netherlands: Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum and the Kroller-Muller Museum in Otterlo. Both have large numbers and are well catalogued.

Most of the major museums in mainland Europe (Paris, Berlin, Munich, Zurich, Brussels, Oslo, Budapest, Rotterdam etc.) and America (New York, Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago, Providence) have small but important groups of Van Gogh drawings or single sheets.

Van Gogh drawings in the UK are scarce. They are to be found in London at the British Museum and Tate Modern and also in Manchester (Whitworth Art Museum) and Walsall (Garman-Ryan Collection).

The most important thing to remember when looking at Van Gogh’s drawings is that they have nearly all suffered enormously from fading either through over-exposure to light owing to popular demand, or because of the chemical changes of the various inks the artist used. In the case of the works in softer media (charcoal, chalk, pastel) there may be some rubbing depending on the effectiveness of the fixative.

It is not always the case that you are seeing what the artist intended and it should be borne in mind that Van Gogh was often short of materials and models and so was forced to compromise or experiment. He was fond, for example, of using different kinds of pens—steel nibs, quill and reed pens cut by himself.

What were some of the biggest challenges in writing this book?

The principal challenge was to assess the enormous amount of literature on Van Gogh and to identify which biography/ book/article/lecture is useful for your background reading, or the development of your argument. Not everything published is relevant and so you have to develop a sense of what is constructive and what is misleading or erroneous.

The other matter is to see as many of the drawings in the original as possible. No reproduction ever does justice to seeing an item in the flesh and handling it.

My other concern is to establish Van Gogh in the context of European art as a whole in order to acknowledge his place within it. He learnt as much from his predecessors as his contemporaries by looking, listening and questioning. It was important therefore to display his innate intelligence (most great artists have innate intelligence) by quoting from the numerous letters that he wrote throughout his life mainly to his brother Theo.

Beyond showing his personal mental strains and anxieties, the letters reveal his eloquence and also how widely read he was in several languages and how diverse his interests were.

The evidence for Van Gogh as an intellectual is as convincing as the evidence is for his mental problems, but this is often overlooked.

Van Gogh comes into that rare category of those whose output on paper needs to be examined with the utmost care — every scratch and every mark. This puts him in the same group as Leonardo da Vinci, Durer, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Rubens, Goya, Picasso, Matisse. In this sense Van Gogh was the true successor of his countryman, Rembrandt.

Finally, you were the Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures in the Royal Collection for 17 years. I have to ask, what was that role like?

I was appointed Surveyor of The Queen’s Pictures in 1988 and retired in 2005 aged 60. There were many changes during this period mainly as a result of the fire at Windsor Castle in 1992 after which the Royal Collection — while remaining part of the Royal Household — was administered (as it still is) by a Board of Trustees. This gave it greater independence and aligned it more closely with other collections housed in museums and galleries.

The Royal Collection is dominated by history and it is a unique survival in so far as it is still displayed in those buildings for which it was brought into existence having been formed by the tastes and interests of Henry VIII, Charles I, George III and George IV, and Queen Victoria. The post of Surveyor goes back to the reign of Charles I when Abraham van der Doort was appointed in 1625.

The 7,000 paintings and 3,000 miniatures which I looked after are housed in the residential and non-residential palaces of the monarch. I was responsible for the presentation, conservation and study of the paintings and miniatures, as well as organising exhibitions in The Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace (redesigned for the Golden Jubilee in 2002) and overseeing loans to exhibitions nationally and internationally.

My years in office were overshadowed by a series of events (fire, divorces, death), which led to widespread criticism of monarchy and its role. The Royal Collection, for instance, was accused of being ‘strictly private’ and ‘inaccessible’ when it fact it was fulfilling its proper function as a suitable setting for the head of state and had an important role in the constitutional role of the monarch.

The response in my time was to make the palaces and the collection more accessible and this was done in the following ways: opening of the State Apartments in Buckingham Palace (1992), re-presentation of many of the royal residences, extensive loans of paintings to regional galleries in the UK and exhibitions in New Zealand, Australia and Canada (known as the Realms); creation of exhibitions for the opening of the Sainsbury Wing at the National Gallery (1991) and other such exhibitions of paintings and miniatures; the making of a television programme in six parts commissioned by Channel 4 in high definition (the first time) with a supporting book (1992). These are only some of the ways in which the attempt was made to bring the Royal Collection more into the public domain and overcome the criticism that it is a ‘private hoard’.

At the end of my time Lucian Freud expressed his wish to paint The Queen to which she agreed. On completion, the portrait was given by the artist to the sitter.

*A purchase made through links in this newsletter results in a small but valuable commission (at no extra cost to you) for this website