Renaissance in the North: Holbein, Burgkmair, and the Age of the Fuggers is a magnificently illustrated, intensely detailed and informative work of scholarship that brings together a spectacular array of works of art from two large exhibitions at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, under the title Holbein and the Renaissance in the North (which closed on 18 February) and renamed Holbein. Burgkmair. Dürer. Renaissance in the North at the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (until 30 June). The first third of the book brings together nine essays that cast light on the subject, establishing key contexts for the works included. The catalogue is organised into five groups, which span place, patronage, artists and families.

At the heart of the publication is the imperial city of Augsburg, which provided an environment of power, wealth and creativity in which art flourished. Hans Burgkmair (1473-1531) and Hans Holbein the Elder (around 1460-1524) were the most influential in a period of intense artistic activity and production. Renaissance in the North highlights the interactions between artists and craftspeople; Burgk-mair’s dialogue with Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and with Italian artists is demonstrated in The Story of Esther (1528, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek, Munich). Holbein the Elder’s remarkable The Fountain of Life (1519, Museo Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon) is restored to its artistic context here, displaying both Netherlandish and Italian influences.

The Renaissance in the north was about human interaction and ambition as well as technical advancement

Fascinating insight

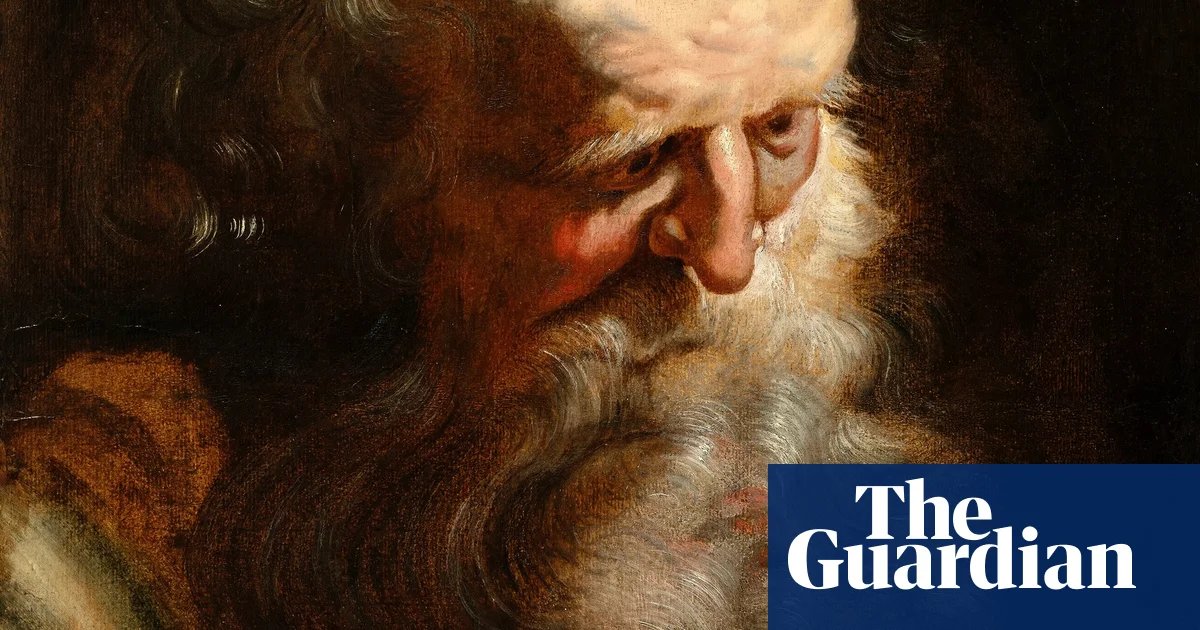

Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543) emerges as the outstanding talent of the next generation, influenced both by his father and Burgkmair. In his contribution, Bodo Brinkmann attributes a recently rediscovered portrait dated to 1512, identified as Marx Fischer, to the young artist, as Holbein’s first known panel painting demonstrating “grippingly powerful realism”. The detailed reasoning of the case Brinkmann sets out provides a fascinating insight into the processes of art-historical analysis, which will be of interest to specialists and more general readers.

Jochen Sander’s essay tracks the formative experiences of Holbein the Younger in Augsburg and during his first decade in Basel, where he moved in search of patronage and away from an increasingly fraught religious situation. We gain a sense of the impact of Holbein’s travels to the French court and Antwerp, with the influence, as argued by Sander, of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin of the Rocks (around 1483-86, now in the Louvre, Paris) on Holbein’s Madonna of Mayor Jacob Meyer zum Hasen (1525/26 and 1528, Würth Collection) and, in Holbein’s portrait of Erasmus (1523, Longford Castle Collection, on permanent loan to the National Gallery, London) the influence of Jan Van Eyck.

Holbein at the Tudor Court picks up on the story of the artist’s career from his arrival in London in autumn 1526—a period arguably more familiar to audiences—with a reputation built on his varied work, from book illustrations to building façade murals and portraits of city leaders. Holbein is usually described as having arrived with a letter of recommendation from Erasmus to Thomas More, and that is followed up here with a series of studies of members of the More household that resulted in the More family portrait (subsequently lost to fire). We are reminded that Holbein and his brother Ambrosius worked together on the frontispiece for an edition of More’s Utopia, published in Basel in 1518, giving an earlier connection between artist and patron and also showing the breadth of media across which Holbein worked. The focus of this book is predominantly on Holbein’s portrait drawings, 80 of which are in the Royal Collection.

Heard’s introductory essay and catalogue entries draw together the insights achieved through recent technical studies of Holbein’s work. We catch glimpses of his working practices, revealed through his use of coloured chalks, inks and watercolour, and the preparation of his paper with pink colour washes. A 1527 drawing of William Warham, the Archbishop of Canterbury, uses black, brown and yellow chalks to bring to life the face of a man in his mid-70s who found himself awkwardly in dispute with his king, Henry VIII. Stylus marks on this and other drawings show us how Holbein transferred images to become panel paintings. The drawing and panel painting of William Reskimer (around 1536-39) are brought together to demonstrate how Holbein worked back and forth between the two to perfect the profile of his subject. Similarly, recent conservation of the portrait of the German merchant Derich Born (1533) has revealed considerable reworking of the outline of Born’s face to achieve a contoured and flattering result. The newly restored image is a highlight of both exhibition and catalogue.

Tracing networks

Described as “a masterclass in manipulating materials to convey a likeness”, Holbein’s drawings remind us of the human dimension of Tudor history but also of the professional expertise that Holbein employed to win commissions and renown. The vividness with which Holbein captured his subjects is communicated through the lavish illustrations and Heard’s discussion. But there is more to this book, which traces networks from the court and into the sociable networks of East Anglia, reconstructed through groups identified in Holbein’s drawings. A series of connections are established between the Lestrange, Lovell and Vaux families; also the marriage links of the Poyntz and Gage families to Lord and Lady Guildford, early patrons of Holbein in England. Beyond the court, the Norwich notary Sir Thomas Godsalve and Sir William and Margaret, Lady Butts, remind us of the spread of wealth in Norfolk and the aspirational dimension to portraiture. Holbein’s drawing of Sir Thomas’s son John Godsalve (around 1543) shows an unusually thoroughly worked-up drawing, painted in black and brown inks with azurite used for the subject’s sleeves and the background. Heard suggests that its inclusion in the collection may indicate that Holbein was working on the drawing at the time of his death, a final insight into a remarkable career.

Along with Holbein, Hans Burgkmair—shown in Lukas Furtenagel’s Hans Burgkmair and his wife Anna (1529)—was a highly influential figure

© KHM-Museumsverband

Both catalogues emphasise the significance of a wider community of artists on each other’s work. Heard places Holbein the Younger’s art within its European context, a welcome reminder of the internationalism of the Tudor court and the importance of understanding it in these terms rather than through a narrow frame of English exceptionalism or Holbein’s undoubted talent alone. We are usefully reminded that the development of the art of the Renaissance in the north was about human interaction and ambition as well as technical advancement.

In bringing together the directions taken in recent studies, these catalogues provide exciting insights into the discoveries that have been made through the application of new technologies and, simply, through close observations of the traces of how artists worked, seen in their drawings and also in completed works, where imaging equipment allows us to see beneath the surface paint. They speak both to the vibrancy of German Renaissance art and to the quality of its scholarship. With a new catalogue by Susan Foister of German paintings before 1800 at the National Gallery, London, due to be published soon, we can look forward to further discoveries and continuing debate, revealing more about the artists and patrons of this remarkable period of artistic production.

• Guido Messling and Jochen Sander (eds), Renaissance in the North: Holbein, Burgkmair, and the Age of the Fuggers, Hirmer, 360pp, 287 colour illustrations, £52 (hb),

published 28 December 2023

• Kate Heard, Holbein at the Tudor Court, Royal Collection Trust, 160pp, 86 colour plates, £29.95 (pb), published 9 November 2023

• Janet Dickinson researches the history of the court and elites in early modern Europe. She teaches at the department for continuing education at the University of Oxford and for New York University in London