“So this is the tale of how Tyngauld the rake acquired his beloved mustache-sword. No, it isn’t a sword for trimming mustaches, it’s a sword hilt with a mustache sticking out of it where the blade would normally be. What’s the point, you ask? Why a mustache-sword? You’re about to find out.”

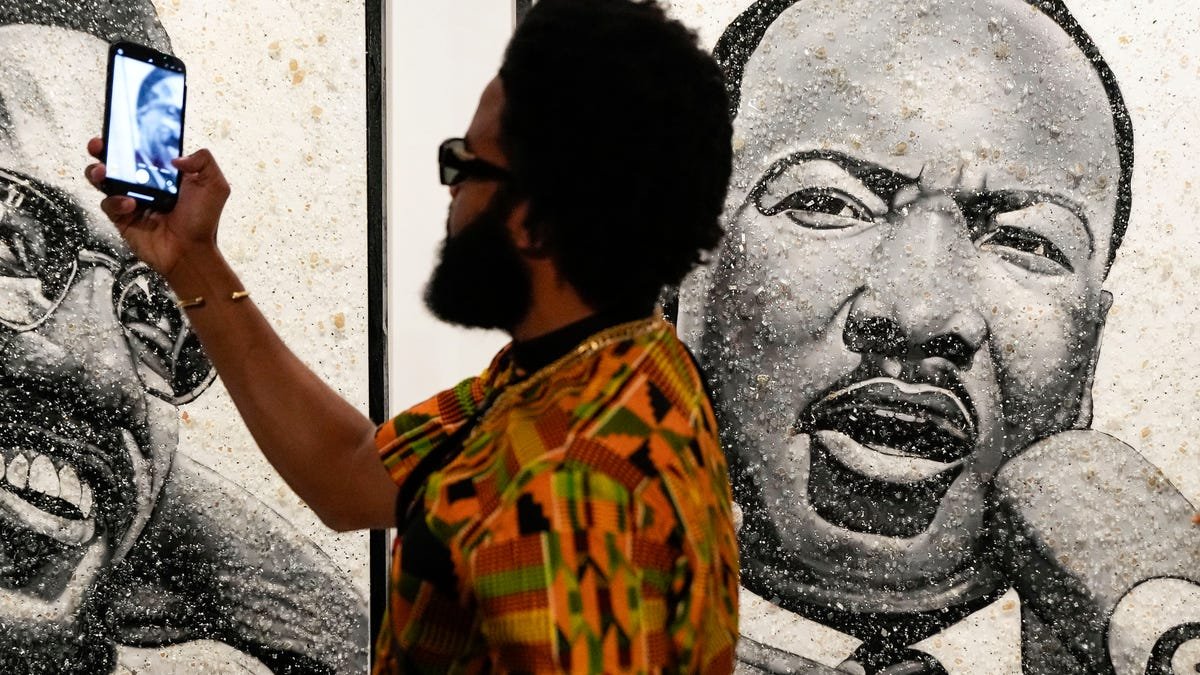

Back in 2010, I had one of the best interview experiences of my journalistic career: two hours talking to cartoonist and author Lynda Barry about what it takes to get adults comfortable with making art. Barry’s signature work, Ernie Pook’s Comeek, was a quirky, often dark, often joyous four-panel experience that was like nothing else in the comics space. But it had been published primarily in independent newspapers, and those were drying up all across the country. With the comic ended, Barry shifted to writing books inspired by her time teaching art classes for adults who came from “many different circumstances, from prison to graduate students.”

Over and over, she found that adults would flinch when asked to draw something, out of a fear that they weren’t objectively talented enough to impress other people. Where a kid can sit down with crayons or paints without any sense of self-consciousness, she said, adults assume that if they create something that isn’t technically competitive with professional work, they’re exposing a weakness.

As Barry put it, if you give a 4-year-old a paper and paint, and they refuse to touch it, “we worry about her emotionally” — but the same refusal in an adult just seems normal. Barry was fascinated with figuring out why at some point, drawing for fun stops seeming like a natural impulse, and starts to seem — well, childish.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25456894/Sword_Loser_Cover.jpg)

Image: Jackson Tegu

I’ve thought about that conversation a lot over the years, especially as I encounter more and more small indie RPGs built around creating artifacts of play at the table, whether it’s cutting out paper snowflakes in To Serve Her Wintry Hunger, making a conspiracy string-board in The Slow Knife, or creating an entire journal in prompt-based solo games like The Field Guide to Memory. Games like these offer adults a framework for crafting, writing, and drawing to tell a story. But they also offer an excuse to experiment creatively, without high-level expectations. There’s a sense of shared, distributed burden in these games, with the whole table collectively dissipating any lingering guilt or awkwardness around drawing just for satisfaction and relaxation. If we’re all doing this, and we’re all adults, this is an adult thing to do, right?

Which brings me to the enjoyably awkward, hilarious experience of playing Jackson Tegu’s Sword Loser, a storytelling RPG fundamentally about creating a library of “badly drawn pictures of swords,” then weaving a tale around them. Tegu, a Pacific Northwest-based designer whose games can be found at a variety of sites where indie games are published, including for subscribers on Patreon, created the first iteration of Sword Loser for backers in 2018, expanded it for convention play, then eventually funded an illustrated zine version via Kickstarter in 2019, along with a companion drawing-based RPG, Tool User. Sword Loser is currently available for purchase at Itch.io.

In Sword Loser, players sit down together and draw some cool swords on index cards. The definition of “cool” is entirely up to the artist; in my original playthrough, at the 2019 Origins Game Fair, one person lovingly drew a triple-bladed, flaming, black-hued, skull-hilted weapon, while others drew cartoony swords that doubled as, respectively, a trebuchet, a corkscrew, and a mustache. There’s no sense of ownership around these sword drawings — they all go into a common Sword Pool.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25456877/RingSword.jpg)

Image: Alice Steuer

The point of the game isn’t just to draw cool swords, although that’s plenty of fun on its own. The game does have a short rulebook that players are meant to read through together; it includes the backstory on the titular “sword loser,” Tyngauld, a lovable, frequently intoxicated rake who’s terrific at using swords, and terrible at keeping track of them.

Play rotates around the table. During their turn, players can either pull any sword drawing from the Sword Pool, telling the story of how Tyngauld acquired it, and moving it to a play area called Tyngauld’s Chambers, or take a sword from the Chambers and narrate how Tyngauld lost it. Maybe he fought a ferocious dragon with that three-bladed, skull-handled monster, and was forced to bury the sword afterward, still embedded in the dragon’s iceforged crystalline heart, preventing the monster’s resurrection. Maybe he got drunk and left that three-blade sword at one of the many taverns on his latest pub crawl, and was deeply embarrassed the next morning when he went looking for it and found out it had burned down his favorite inn. Either way, it’s gone, and you move on to the next sword story.

Sword Loser is extremely freeform, with no set amount of play time: Tegu suggests somewhere between 20 minutes and an hour, depending on the number of players and how long everyone’s still enjoying the game. As the rules put it:

There is no gaining of points, no keeping of score. There’s no winner, or rather, there’s only one loser and we’ve already met him. You’ll know the game is over when there’s a general feeling of having had enough.

Even five years after my own hour-long game, I still remember Sword Loser vividly and fondly. It made an impression on me because its structure so neatly gets around the barrier Lynda Barry was exploring and trying to smash through. This style of RPG expressly invites grown-ups to sit down and create something, with no expectations of world-class talent, and no sense of competition or comparison.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25456814/EyeSword.jpg)

Image: Tasha Robinson

No one expects high artistry out of a quick index-card sketch of a sword. All the game is looking for is creativity, specificity, and interactivity. Two swords tied together at the hilts to make sword-chucks, a sword spotted like a Dalmatian, a ludicrously large sword or a ludicrously tiny one — those are fun to come up with and fun to draw. They’re also fun to hand over to everyone else at the table as a subtle challenge: Can you make something memorable and enjoyable out of this particular prompt? I dare you to try.

The game is also expressly designed for collaborative creativity, and to foster a shared sense of participation and engagement. The rules encourage players to listen to other participants’ stories — and draw more swords for the Sword Pool while they listen. There’s a relaxing communal feeling to sitting around doodling swords while listening to other people’s Tyngauld tales, somewhere halfway between modern art therapy and the ancient ritual of spinning tales together around a fire. But in this case, it’s expressly clear that doodling isn’t checking out, it’s opting in. Every new piece of sword art on the table gives the next storyteller more options.

For players steeped in past roleplay experiences, swords are the perfect subject for this kind of game. They suggest adventure and intrigue — enemies to overcome, fighting skills to acquire or sharpen, sparring and competition, or combat and survival. Games like Dungeons & Dragons and its many imitators are packed with diverse, exotic weapons options, but the sword is iconic and cross-cultural. (There’s a reason nobody makes bittersweet, thrilling animated shows about the best mace-maker in a country, and their relationship with the best mace-wielder.)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25456815/Very_Magic_Shortsword.jpg)

Image: Tasha Robinson

What I love most about Sword Loser, though, is that it invites adults to play exactly like kids do, by making up a thing and telling a story about it, without any self-consciousness or shame. You could certainly play this game with children without any rules modifications, but my experiences with it have all been with adults — some of whom, as Barry foreshadowed, came to the table apologetic or reluctant because they weren’t confident about their art skills. Making Sword Loser a silly icebreaker game about over-the-top swords certainly helps defang that anxiety: People have more space to be self-deprecating about their art in a game no one’s taking too seriously.

Like most storytelling games, however, Sword Loser can adjust to any tone the players can agree on. Tyngauld is written as a bit of a twit, but he’s also meant to be a master swordsman. You can certainly turn Sword Loser into a dramatic story about heroism and battle. He might be a frustrated adventurer whose epic-class battles are so onerous that they inevitably destroy his weapons. He might be a fighter under a powerful curse, prone to losing weapons just before the fight where he most needs them, and constantly struggling to survive long enough for the next battle.

It all just depends on what you want to draw, and what kind of story you most want to tell. Just a word of advice: If you want to play Sword Loser as a straight and serious game about lost swords and lost hopes, maybe don’t sit down and draw yourself a mustache-sword.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25456812/MustacheSword.jpg)

Image: Tasha Robinson