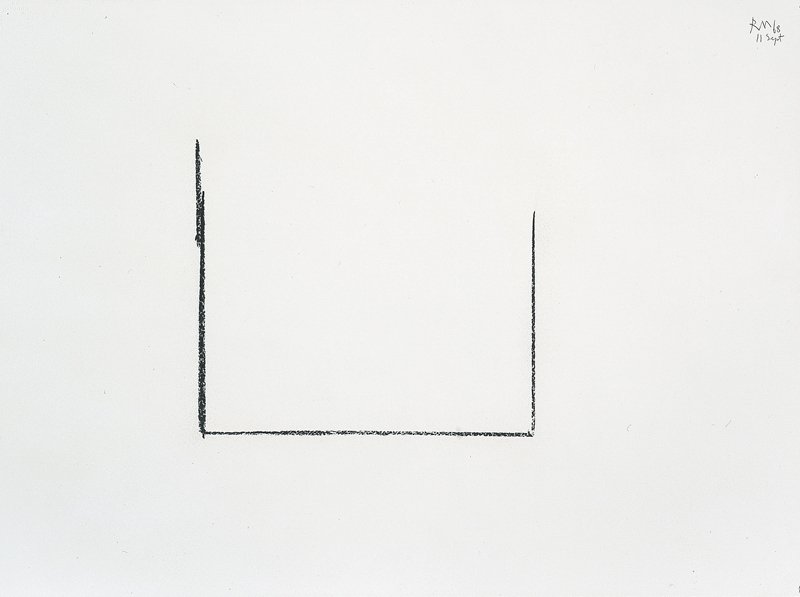

Why not open right here with Motherwell’s “Opens” starting in 1967? These drawings need no elaboration. As the artist himself pointed out, their famous origin was simple. He had seen one of his paintings leaning against a larger, more vertical painting and had outlined in charcoal the edges of the small painting on the larger one, creating a door-like image. He then found the proportion “rather beautiful … I brought it home from the studio to look at it, and one day decided to turn it upside down, so that the ‘door’ became a ‘window.’”

How wonderful it is that the “Open” drawn on September 11, 1968, in charcoal on paper, his preferred support, should be the only one inscribed with a specific date rather than just the year. As if the others were to be left open regarding the time of their exact creation. Equally wonderful is the fact of this drawing’s non-inclusion in Marlborough’s first exhibition of the “Opens” in May 1969, although it is reproduced in the catalogue. That the title was changed to Open Study No. 1 in the 1970’s signals the unique importance of this drawing: both singly inscribed and non-continued in that way, both open by title and omitted in presentation. Surely, this stresses the importance both overall and underneath of the motif of openness. I am especially happy to have been in many conversations with Motherwell about the “Opens,” as about the open movement in American poems, some in Wallace Stevens, and some in Robert Frost, about whom he was particularly enthusiastic: see his Tree of My Window (Robert Frost) of 1969, in my Robert Motherwell: With Pen and Brush (Reaktion Books, 2003).

Motherwell’s “Opens” in their rectangles leave everything deliberately incomplete. As do all his “Elegies.” They feel to me transcriptions of an often-unspecified voyage, of a nation, of a person, of an ultimately heroic myth. His “Elegies,” in lamenting not just the perished matador in the heartbreaking Federico García Lorca poem saluting him (“A las cinco de la tarde / At five in the afternoon”), but also our own present voyage towards our perishing, remain somehow open to the future.

The Reconciliation Elegy of 1978, the magnificent mural that had been commissioned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, has an open space like a white and empty margin that Motherwell longed to fill in, as he told me one day when we were looking at it together on the wall of his studio. He had wanted the mural to be “as clear and personal and unarchitectonic as a human voice, retaining the immediacy, say, of oriental calligraphy in a work of huge enough scale … that must hold, both close-up and from 100 feet away.” Motherwell was ill when the mural was installed and never saw it hanging until the evening preceding the opening in the museum. He felt that void to be watering down the intense reconciliation to the world he had intended and proposed a revision to fill in the empty space. (See Motherwell’s untitled drawing in marker and pen [below] from 1980.)

Walt Whitman’s poem “Reconciliation” speaks loudly of what we sense in the painting and the proposed revision as “Word over all, beautiful as the sky! / Beautiful that war, and all its deeds of carnage, must in time be utterly lost, / That the hands of the sisters Death and Night, incessantly softly wash again, and ever again, this soil’d world…” Something about the heroic stance of the artist tackling this epic task, with the massive, long brush he used, is as recognizably American as could be imagined in its breadth and largeness. Motherwell, endowed with largeness of person and personality, created spaciousness in his works, painting and drawing. That his Reconciliation Elegy was never exhibited in its redone state, when it would have been gloriously reconciled with its former rendering, the space filled in, leaves this elegy metaphorically, and visually, also open. In the authoritative catalogue raisonné of his drawings, we can see those drawings of both the exhibited Reconciliation Elegy in its original state and the never exhibited, redrawn or “repaired” Reconciliation Elegy are now reconciled. As if the notion of Elegy were to have been originally about openness in time, and incompletion, like the “Opens” themselves. Something like a miracle uniting thoughts and realizations brought together, reconciled, yet left open to themselves as to each other.

That paper should have been Motherwell’s preferred support, as he reiterated, bestows on his drawings a kind of perfection. The artist was endlessly haunted by this wish to repair and reconstruct. His longing for reparation was quite a deeply surrealist haunting: “Tell me whom you haunt, and I’ll tell you who you are,” said André Breton.

I am imagining the Elegy as a lament and a triumph, as a voyage traveling back to remembrance and simultaneously forward, and as also an “Open,” leaving the space and time beyond it open to an ultimately authentic proof of reconciliation.