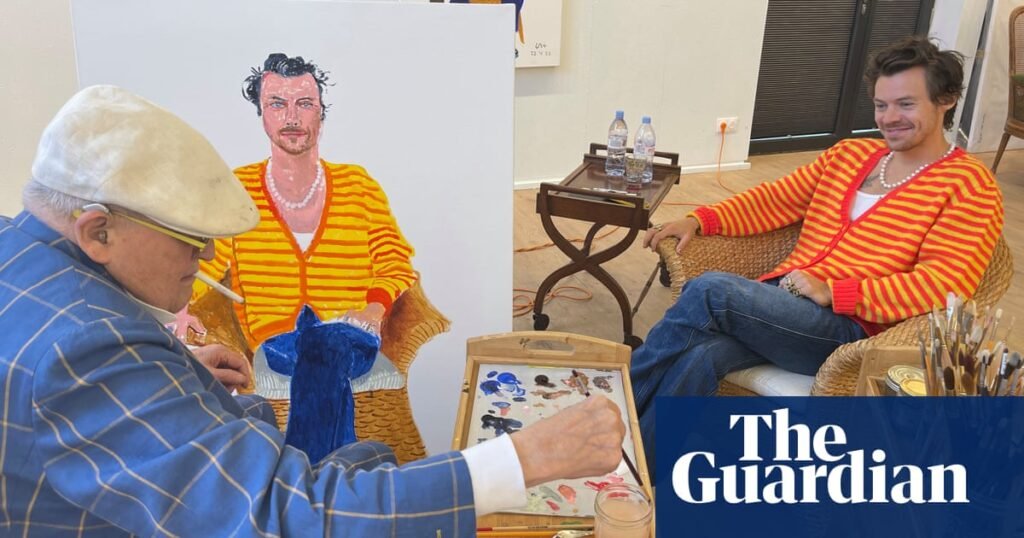

David Hockney draws better than anyone else alive today. There may be other fine painters around, but on paper, with charcoal, ink pen or even crayons in hand, he is incomparable. So of course his retrospective of portraits on paper opening this week at the National Portrait Gallery is called Drawing from Life.

Hockney has always had a deceptively simple and absolutely captivating ability to look at his own face in the mirror, or at his “muse” Celia Birtwell, or at flowers in a vase, and set down what he sees, in clear, confident lines that vibrate with vitality.

Hockney’s eyeballful of a show, which had a brief three-week run in early 2020 before it was closed by the pandemic, reopens at a time when drawing from life is becoming ever more popular. And not just any drawing from life, but particularly life drawing, that of the human figure.

The events site Eventbrite lists nearly 500 life drawing classes coming up in the next few weeks alone around Britain, from Brixton to Exmouth.

Nudes have long featured in Hockney’s oeuvre, especially in the 1960s, when he sketched friends and lovers lying on sofas in relaxed Californian languor. He has also oil-crayoned Celia lushly nude. Now demand for life drawing classes is outstripping all other subjects such as landscapes or still lifes.

In London alone, the classes currently on offer include Full Bodied, where you sample sommelier-selected wines as you sketch a nude – a few glasses and you’ll think you are Picasso – and Neon Naked Life Drawing classes, where the models are “adorned with UV paints and accessories”.

Options range from queer life classes, life classes for young people, and high-end classes at the Royal Drawing School. Life drawing is also becoming more popular with hen and stag parties across the UK.

The craze has undoubtedly been stimulated by Tracey Emin, who leads regular life classes at her art school in Margate and has spoken of how her art was changed by experiencing one a few years ago in New York.

Emin is also an influence on the way life drawing is now being enjoyed as a therapeutic, “mindful” way to slow down and sense your being. “Once you get going,” she told me earlier this year, “you can really enjoy it: you enjoy looking, you enjoy seeing, and you enjoy slowing down because you’re seeing in a different way. And then after that drawing class, you see everything differently.”

But is artistic drawing as Hockney does it the same thing as drawing in a mindful life class? Are we perhaps missing how hard it actually is to draw well? Artists who have drawn from life over the centuries may or may not have been spiritually enriched by the time they spent staring at faces, bodies or the natural world. They were, however, doing something whose purpose was not therapeutic. They were trying to see and record visual truth.

after newsletter promotion

Hockney is heir to that searching tradition. He calls it “eyeballing” – and it’s hard work. It is not necessarily uplifting, either, for the truth isn’t always pleasant. Some of Hockney’s most powerful drawings are his self-portraits – not ennobled, expressionist visions, but clinically accurate renderings of his image in the mirror. Often he shows his drawing hand too. He has drawn himself as a bespectacled teenager in Bradford, much later with a hand cupped over his ear to show his increasing deafness, and as a man whose elderly face might be someone else’s as he delineates it faithfully, unswervingly.

For drawing as it is practised by Hockney is more science than spirituality. The greatest draughtsperson of all was Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawings don’t stop at the skin, but cut under it to reveal organs, arteries and bones in anatomical drawings based on his own dissections of corpses. Were such “death classes” conducive to wellness? No. Leonardo wrote of the horror and disgust he felt carrying out his anatomies late at night with blood spattered everywhere. But the knowledge was well worth the sacrifice; his drawings record details of human anatomy that no one had seen before him.

Hockney is a great exemplar of Leonardo’s belief that drawing is about steadily seeing nature’s truth. His youthful studies from the 1950s demonstrate an absolutely absorbed, fascinated eye learning to see. But the kind of art education he and Leonardo da Vinci shared – in which the student must draw, draw and draw again from other artist’s works and from life – has given way to much more varied art-school curricula. This is proving a problem now that artistic fashion has shifted from postmodern media back to painting.

So the rise of the life class is a fascinating moment. In some ways, it seems a mindful indulgence, inviting us to splurge out our “artistic” impulses without any pressure to draw particularly well. Then again, with so many people signing up to sketch the human figure, perhaps a new Hockney will emerge: someone who doesn’t just enjoy the wine-fuelled vibe, but relentlessly eyeballs the model, hand moving with deadly accuracy on a sheet of paper, seeing us as we are.