CLEVELAND, Ohio — Climate activists around the world are invading art galleries and museums, splattering artworks with paint, soup or mashed potatoes and gluing themselves to picture frames to draw attention, pardon the pun, to their cause.

Manabu Ikeda, a Japanese artist born in 1973 whose work is the focus of a smashingly good exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, has flipped the script. He’s making some very powerful art to raise awareness about human-centered hubris and the potential for catastrophic environmental change caused by out-of-control technologies.

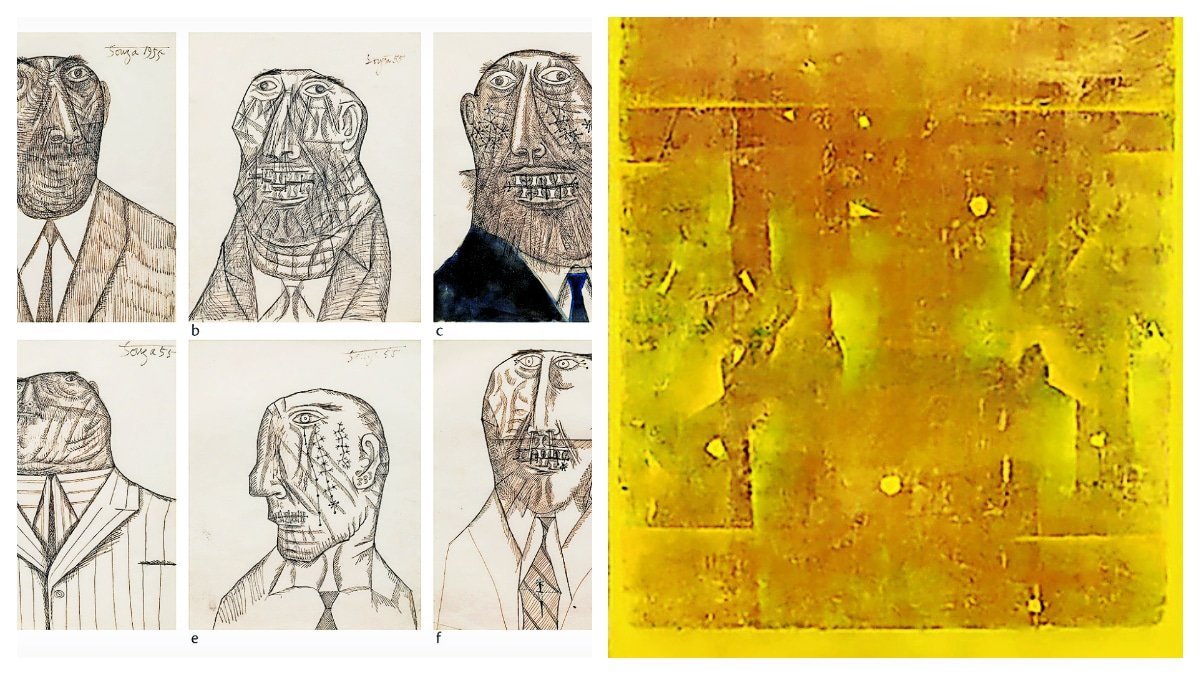

In Ikeda’s ferociously focused and microscopically detailed drawings in pen-and-ink and pencil, willow trees dangle branches of barbed wire. Flowers bloom with petals shaped like the radiating triangles in the international warning symbol for radiation.

A cruise ship that brings to mind the Costa Concordia, the hapless Italian liner that crashed into the rocky Tyrrhenian coast in 2012 comes to grief on a ridge below the icy summit of Mt. Horai in Japan, turning the peak into a modern day Mount Ararat.

These few examples, all modestly scaled drawings on paper, are a small sample of more than 60 works on view in the MOCA show, Ikeda’s first North American retrospective. Organized by the Audain Art Museum in Whistler, British Columbia, the exhibition, titled “Flowers from the Wreckage,” includes vast apocalyptic panoramas of entire cities convulsed in minutely described Godzilla-like catastrophes that have an exhilarating, cinematic sweep.

Ikeda’s latest work, now underway at MOCA, is a wall-size seascape of crashing waves and cloudscapes drawn in a manner so sharply realistic that Ikeda seems to have miraculously channeled the ability to generate perfectly scaled fractal patterns of waves and clouds.

According to MOCA, the artist will be hard at work on the seascape drawing in a publicly accessible gallery in the show from 1 to 3 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday April 18, 19 and 20, demonstrating his drawing skills live and in-person.

A native of Saga, Japan, Ikeda earned a bachelor of fine arts from the Department of Design at Tokyo University of the Arts in 1998 and followed up with a master of fine arts from the same school in 2000. He spent a year in Vancouver, British Columbia, as a research artist sponsored by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs, and has worked since 2013 in Madison, Wisconsin after participating in a three-year fellowship at the Chazen Museum of Art.

According to materials available in the show, Ikeda creates his vast tableaux by diving in without a preconceived plan. He simply generates imagery as he goes. But it’s clear he has an amazing ability to bring qualities of unity and overall design to his compositions, even though he works close to the drawing surface in a way that requires him to mentally balance micro and macro scales while working.

A time-lapse video clip on the MOCA website shows Ikeda in action, as he makes a drawing on a horizontal surface. A ladder positioned in the studio/gallery at MOCA also shows that Ikeda needs to keep checking how things are adding up at a larger scale by climbing up to get the bigger picture.

Back to basics at MOCA

The Ikeda exhibition is a welcome event at MOCA Cleveland because it feels like a return to the museum’s roots as a place committed to displaying excellent work from areas of contemporary art beyond the scope or reach of the Cleveland of Art, at one end of the city’s artistic ecology, and the far smaller nonprofit Spaces gallery, at the other.

More arts stories by Steven Litt

Founded in 1968 in a small storefront on Euclid Avenue in University Circle, MOCA Cleveland has never been afraid to pick cultural or political fights. But since the COVID-19 pandemic and some missteps over its handling of a show focusing on images of police violence against unarmed African Americans, MOCA has focused on exhibitions that seemed to place politics of diversity, equity and inclusion over concerns for artistic quality. The shows have often felt overly didactic and text-dependent, as if the museum were adopting a position of moral instruction. Such a stance could be acceptable and defensible if the art on view were exciting and well-made, but that hasn’t always been the case.

With the Ikeda show, MOCA feels as if it’s coming back to first principles. Also on view now are shows that feel related to the Ikeda exhibition in various ways. An installation organized by Los Angeles-based Andrea Bowers, a native of Huron, Ohio, explores contemporary activism focused on raising awareness over environmental dangers facing Lake Erie and the Great Lakes. Part of the exhibit includes a collaboration between Bowers and Cleveland artist David Helton that resulted in “Lake Erie: Exist, Flourish, Evolve,” a neon sign mounted temporarily on the Great Lakes Science Center.

The exhibition coincides with a two-day conference at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on Earth Day, Monday, April 22, and Tuesday the 23rd organized by the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund on the topic of “Truth, Reckoning & Right Relationship with the Great Lakes Conference.”

MOCA’s ground-floor gallery features “SCRD GRDN,’’ an exhibition of surreal, mural-sized paintings of human figures and gemlike forms on black backgrounds by BlackBrain, AKA Ariel Vergex, a native of the Dominican Republic now based in Cleveland.

The BlackBrain show, with its emphasis on fantasy, and the Bowers exhibition, with its focus on ecological foreboding and environmental awareness, feel related to the Ikeda exhibition. But it’s very clear that the latter is the center of gravity and the main reason for a prolonged and very rewarding visit.

East-West fusion

Part of what makes the Ikeda show so entertaining is that it’s packed with cultural and art historical references that embrace Asia and the West.

“Foretoken,” a 2008 drawing of a tsunami-like civilizational collapse, is a contemporary riff on the iconic 1831 Japanese woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai, the “Great Wave off Kanagawa,” in which a great, curling, foaming wave crests in a vortex so big that it appears to swamp the distant snow-covered cone of Mount Fuji. In Ikeda’s version of Hokusai’s vision, a curving mountain of water is actually made of shattered apartment buildings, power plants, foundering ships, swirls of highways and interchanges, amusement park waterslides and all manner of manmade junk swept up by a massive inescapable force hurling everything toward a horrific doomsday.

pen and acrylic ink on paper, mounted on board

190 × 340 cm

Collection of Sustainable Investor Co., Ltd. (Kagura Salon)

Yasuhide Kuge

The imagery in “Rebirth,” a monumental 2016 drawing measuring 10 feet high and 13 feet across, is so vast, rich, complex and minutely rendered in microscopic detail that the work is accompanied by an interactive video display that invites a viewer to click on circled portions of the composition for a detailed visual exegesis.

The drawing, housed in a glass-enclosed display case to protect it, represents a massive tree swamped by a tsunami-like wave that threatens to inundate the known world. By tapping on the adjacent screen you learn, for example, that the dome of a building garlanded with twisted railroad tracks in the picture is actually the Wisconsin State capital surmounted by a gilded bronze statue representing the spirit of Wisconsin.

Another button identifies a minuscule camel caravan trekking across a precarious rope bridge in search of an oasis. As the accompanying text proclaims, the image is meant to evoke the restless human desire to seek the ideal place in which to live. “This is us right now,” the text states.

It’s easy in such works to sense echoes of disasters and terrorist attacks, including the September 11 assault on the U.S. to the earthquake and tsunami that inundated the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in Japan in 2011.

The moralizing in Ikeda’s work is made palatable because his virtuosic skill as a draftsman commands a viewer’s attention. It’s the platform from which he delivers sermons on humanity’s heedless drift toward the abyss. Despite abrupt shifts in scale, texture and subject matter, Ikeda never seems to have an off moment in which his facility fails or his skill can’t keep up with his imagination.

Quite often, Ikeda creates imagery out of substances, objects, organisms or materials that stretch or warp reality. His aforementioned willow tree is made of barbed wire. He imagines a voracious city that turns into the head of a gargantuan snake. He constructs a grand staircase out of water. He depicts a praying mantis made of grass. Somehow, it all works, beautifully.

pen and acrylic ink on paper

23 × 29 cm

Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin–Madison John H. Van Vleck

Endowment Fund purchase, 2013.25

Kei Miyajima

Ikeda’s illusionistic techniques include a thorough command of relationships between figure and ground, also known as positive and negative space. In one drawing, a flock of birds is described by reserved areas of blank white paper surrounded by the dark curtain of a night sky. The same drawing somehow shifts viewpoints so that fragments of the night sky break into pieces to turn into birds silhouetted against a white sky. Ikeda does these things as if with a shrug, indicating that for him, it all comes easily.

Deep art historical currents run through Ikeda’s work. He channels the 19th-century Euro-American tradition of using landscape to express the sublime — a notion of man’s puny presence amid the forces of nature — evident in the works of painters such as J.M.W. Turner or Frederic Edwin Church. His illusionism brings to mind the consciousness-twisting visual puzzles of M.C. Escher. Ikeda’s fantasy-driven scenes bring to mind the magical dreamscapes of Rodolphe Bresdin and Richard Dadd.

A lesser artist attempting the complexity of Ikeda’s drawings could easily stumble in the gap between microscopic detail and an overall comprehensive vision. But Ikeda is able to unify his compositions through devices including typical Western perspective, as in a view of a mountainous sculpture of Buddha that implies a single point of view. But he also draws on typical Chinese or Japanese modes of depicting landscapes as if they were seen from a point of view that seems to float in space at equal distance from everything the eye sees.

pen and acrylic ink on paper, mounted on board

130 × 162.1 cm

Private Collection

In the 19th century, when Frederic Edwin Church displayed works such as his panoramic view of Niagara Falls, now owned by the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., he equipped viewers with opera glasses so they could savor every detail. In like manner, MOCA is providing magnifying glasses to enable viewers to zoom in for closeups while marveling at the big picture.

Even a climate change denier could find something to enjoy in Ikeda’s work. That could be one of the goals behind his symphonic imaginings of planetary mayhem. For those whose are unconvinced that human behavior is changing the planet, Ikeda’s deeply enjoyable and work just might be able to raise a few doubts.

Art Review

What’s up: Winter-spring exhibitions anchored by Manubu Ikeda’s “Flowers from the Wreckage.’’

Venue: Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland.

Where: 11400 Euclid Ave., Cleveland

When: Through Sunday, May 26.

Admission: Free. Call 216 421-8671 or go to mocacleveland.org.