At a press conference held in downtown New York City this morning, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced the return of an Egon Schiele drawing Seated Nude Woman, front view (1918) to the heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, the Austrian Jewish cabaret performer whose art collection was stolen by the Nazis. Grünbaum died at the Dachau concentration camp in 1941.

This Schiele, a portrait of the artist’s wife Edith, is the 11th artwork that has been returned to Grünbaum’s heirs by the Manhattan DA, in connection with an investigation carried out with the help of Homeland Security and the Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) . Notably, this particular work was returned from the heirs of Gustav “Gus” Papanek, an Austrian Jew whose own family fled the Nazis in 1938 and later purchased the artwork in New York in 1961, unaware that it had been stolen from Grünbaum.

It wasn’t until Gus Papanek’s death, in 2022, that questions about the provenance of the work began to arise. The Papanek family then fully cooperated with the D.A.’s office to ensure the return of the work.

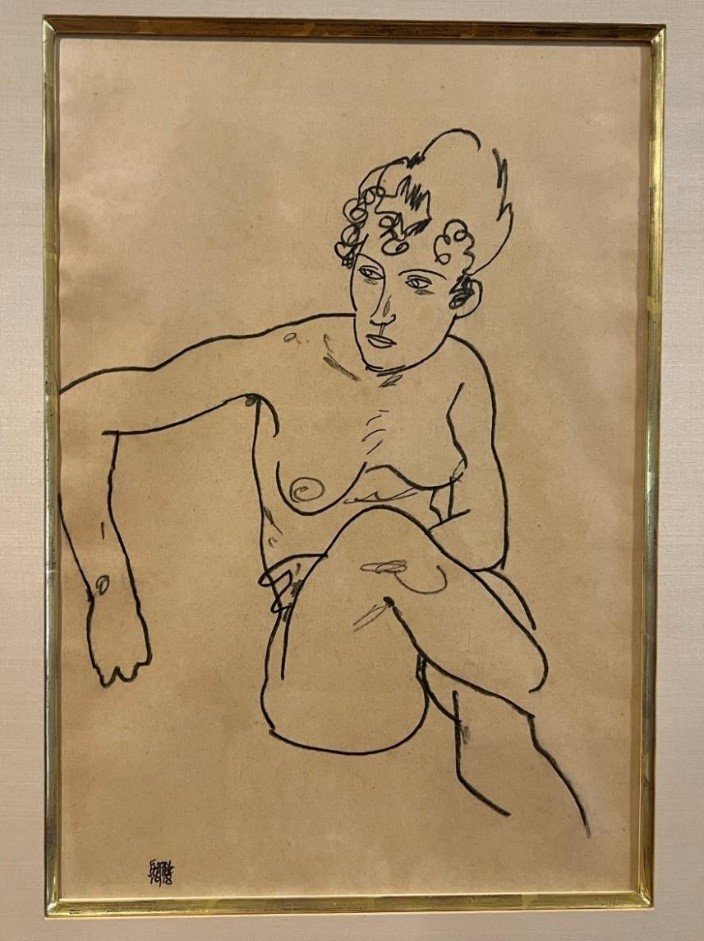

Egon Schiele Seated Nude Woman, front view (1918) at the press conference where return to Fritz Grünbaum’s heirs was announced.

Heirs of both Fritz Grünbaum and the Papanek family were present today for the announcement. They delivered public remarks, as did Bragg, and assistant district attorney and chief of the ATU Matthew Bogdanos and others.

“No matter how many years have passed since the theft,” said Bragg, “it is never too late to celebrate these accomplishments.” He noted that both families involved had been “deeply impacted by the Holocaust,” and praised their “generous, kind, and extraordinary partnership.”

In September 2023, the DA’s office returned seven Schiele artworks to Grünbaum’s heirs. They were returned from: the Museum of Modern Art; the Ronald Lauder collection; the Morgan Library ; the Santa Barbara Museum of Art; and the Vally Sabarsky Trust. An additional artwork was surrendered by collector Michael Lesh to the family in October 2023. This year, in January, two more works were returned from Allen Museum at Oberlin College and from the Carnegie Museum of Art respectively.

Another Schiele drawing, titled Russian War Prisoner, “remains seized in place at the Art Institute of Chicago,” according to a statement from the DA office.

Egon Schiele, Russian War Prisoner (1916).

Paul Reif, one of Grunbaum’s heirs, thanked the DA office for the “hard, often thankless work for justice to so many,” adding that “today, you mark another milestone in your exceptional and groundbreaking work to vindicate the rights of Felix Grünbaum. Your work stands as a bright, shining light, not just to our family but to all other families still working to achieve justice.”

Reif noted that the family has formed a foundation and using the proceeds of sales to underprivileged performing artists. He praised the Papanek family for its “courageous actions” in returning the work.

Grünbaum possessed hundreds of artworks, including more than 80 pieces by Schiele alone. He was captured by the Nazis in 1938 after they annexed Austria and was forced to turn over control of the collection to his wife, Elisabeth, while he was imprisoned at Dachau. Later, Elisabeth was forced to surrender the entire art collection to Nazi officials. She eventually died at a concentration camp.

The art collection was inventoried by art historian Franz Kieslinger, also a Nazi party member, and then placed in a Nazi-controlled warehouse Schenker & Co. A.G. in September 1938. By that time, all works of Schiele had been deemed “degenerate art.” Many were auctioned or sold as part of a program overseen by Joseph Goebbels, then Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda.

According to the DA, Grünbaum’s Schiele collection could not be traced for more than a decade after it was seized by the Nazis.

However, in 1956, the works suddenly reappeared in Bern, Switzerland, where they were sold by G&K Auction owner, Eberhart Kornfeld. Kornfeld sold most of the Grünbaum Schieles to New York dealer and Galerie St. Etienne owner, Otto Kallir, without any provenance or ownership history. After purchasing the drawings from Kornfeld, Kallir then “transported them into Manhattan and then sold them to private collectors, individuals, and institutions,” according to the DA’s description.

Two of those individuals were Ernst and Helene Papanek, Gus’s parents. The Papaneks fled the Nazis in 1938 and emigrated to the U.S. Gus received the drawing as a gift from his parents in 1969 and it remained in his possession until his death.

While settling Papanek’s estate, his heirs saw red flags around the artwork, especially in the light of the DA’s investigation and previous restitutions. They “realized for the first time that there might be problems with the provenance,” said Bogdanos at the conference. “They reached out to both the [Grünbaum] family and DA’s office to—I’m going to say it forever—do the right thing.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: