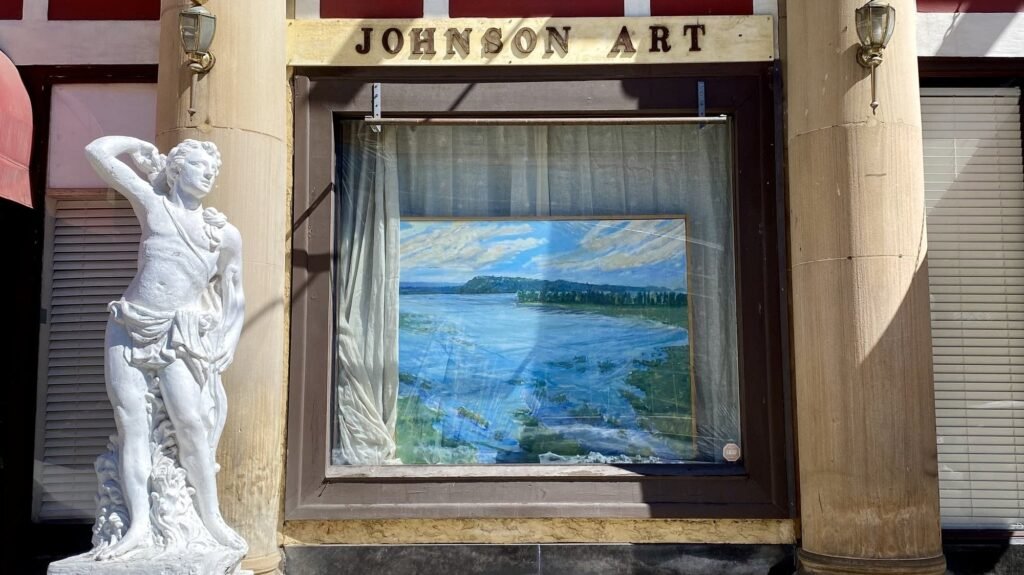

There is a little mystery at 534 St. Peter Street in St. Paul. I pass it on my commute to work.

The mystery is named “Johnson Art.” This is spelled out in hand-placed block letters above a storefront.

The windows are shrouded in white curtains and blinds and always pulled shut. Nudged in front of the curtains is a large painting of the Mississippi. On the sidewalk are two bleach-white Roman statues on plinths. They look like something out of Caesar’s Palace.

Johnson Art is bookended on one end by Peter’s Market, with its “e-cigs” and “cold drinks” advertisements and a withered potted plant in the window. On the other end is the entrance to the red brick and stone Colonnade Building, which runs the length of the block and was probably glorious in some earlier age.

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone – free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

The statues beckon, but I’ve never seen a soul enter or exit the place or even walk by. If it is a shop, surely it can’t be doing well. Or maybe it’s the ruins of a collector’s collection.

On a recent spring day, I remembered to look it up. Nothing. Zilch on Johnson Art. My editor did his own search and was also stumped.

Enough.

I zipped up my parka and walked outside, passing the low-slung History Theatre and the soaring Church of Scientology. I then made my way to St. Peter Street, hopping over melting snow piles along the way.

Approaching on the sidewalk, Johnson Art had no “Open” or “Closed” sign, nor a discernible entrance. There were signs of life, though. On two-column bases were the words “love” and “joy” scrawled in chalk, which seemed like it must be recent. Chalk can’t survive the freeze and thaw of a Minnesota winter, even an unseasonably warm and dry one like this. I found a gap in the blinds and peered in.

A pair of eyes looked back.

The eyes belonged to Karen Johnson, a 70-something woman with short-cropped gray hair who then opened the door that I thought was a window. We were both surprised to see each other.

Retired art professor Dale Johnson with a charcoal ice house drawing at his artist studio and home in St. Paul on March 28.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News

I apologized for snooping and tried to explain my presence. She told me the storefront belongs to a painter, Dale Johnson — her husband. She invited me to come in. She’ll go wake Dale from his nap, she said, walking away as I began to object.

As I waited, I looked around. I was in a well-used living room. It was a room of armchairs with blankets and stacks of books and mail, along with a leather couch and a gray kitty slinking about, and large paintings hung high. One looked like a strip of ocean waves with cloud cover. I found out later it’s the view of Lake Michigan from Grand Haven.

Meet Dale

Dale gingerly walked in and stuck out his hand. He started talking about his art and life like he had been expecting the interruption. I later learn that Dale worked more than 40 years as an art professor at the nearby Bethel University — likely the source of his impromptu lecturing skills.

These skills are tempered with a folksy sensibility, with lots of you knows, and reinforced by his style. Dale wore a plaid flannel shirt tucked into jeans, duck boots and glasses. He wore his gray hair short.

A graying chocolate lab circled him: Princess Leia. She belonged to his late daughter, Lisa. Lisa died from cancer nearly four years ago to the day, Dale told me, pointing to the couch where she used to rest.

A view from Dale Johnson’s studio into the bedroom in St. Paul on March 28.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News

We ventured into his conjoining studio. The room overflowed with canvases and teetering stacks of watercolors and charcoals, so much so that a false step could be treacherous for art. He patted the top of one paper stack.

“This is full of, I think, good things that can be shown, really,” he said.

‘Good things that can be shown, really’

Dale’s artwork maps out a swirling vision of the neighborhood outside: panoramas of the Capitol building and St. Paul Cathedral, a work in progress of the Xcel Energy Center and views of the Mississippi.

The Colonnade Building, where we stood, is also represented: On a colorful canvas, there were the Roman statues and Peter’s Market sign, painted as a blur of white and blue.

“Yeah, paint the neighborhood,” Dale said, chipperly.

The Colonnade was built as a hotel circa 1889 and is now apartments, including the storefront space-turned-artist loft of the Johnsons. They have lived here for about five years.

They explain that it was a good deal — Dale even traded paintings for lowered rent — and close to their kids and grandkids. One of their sons lives in the building. Through a curtained doorway, a bed was visible, tucked among more art and storage. Across from the bed were some of Karen’s photographs and a pencil drawing Dale recently made of their late daughter Lisa as a little kid.

“Oh man,” he said, looking at it. “She lived a life. She was a big joy in our life.”

Trips to Florence

In the studio, on one bookshelf packed with art books, was taped a sheet of paper that said Black Lives Matter in colorful crayon, a gift from one of the grandkids.

On another bookshelf, taped up, was a series of black and white images. One looked torn from a textbook, of an industrial steel sculpture by the 20th-century abstract sculptor Anthony Caro. Another was from probably 30 years ago: Dale and one of his kids smiling at the bottom of a slide. Below that was a tightly framed portrait of George Carlin, staring steely-eyed at the camera.

A hero, Dale explained.

Dale paged through some paintings of Florence, Italy, and its duomo, from one of the several trips there he made with students.

He remembered how they would pack lunches, eat and paint outside in the Renaissance city of art. He also took students to paint in the Dominican Republic, and there are pictures from that, too. He retired in 2012 after a 42-year tenure.

“They never fired me. I am amazed by that,” Dale said of Bethel.

“Why would they fire you?” I asked.

“Well, they’re a conservative school,” he said, and wondered aloud if he should have said that. “You know, I fostered a lot of crazy thinking, good thinking, and was against wars and, you know, just everything that would kind of bother them.”

More than anything else in the studio, there were ice houses, painted on canvas or carved from rough chunks of wood.

After I met with Dale, I read an article from Bethel that was published when he retired. It says he learned under the 20th-century painter Angelo Ippolito as a graduate student at Michigan State University.

Ippolito is known for his abstracted fields of color. I don’t see Ippolito’s influence in Dale’s work — which is more expressionistic, and impressionistic — except for in these ice houses and their bold planes of color.

Ice houses

Dale doesn’t ice fish anymore, he explained that it’s too hard on the body at 78. So he paints the fish houses, maybe more than a thousand now, he said.

Princess Leia lay next to one of these canvases on the floor, a royal blue box framed by impasto clouds and reflections in ice. He’s done many of these from the fish’s point of view, too, he said.

Princess Leia with an ice house painting at Dale Johnson’s artist studio and home in St. Paul on March 28. “I take them and work with them as a metaphor for standing up against all odds,” Dale said of his ice house series.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News

“I take them and work with them as a metaphor for standing up against all odds,” Dale said.

Dale had an exhibition earlier this year at the Lost Fox coffeehouse in downtown St. Paul. Over the decades of his career, he’s exhibited mostly in New York, where he had representation on Madison Avenue. He currently has no shows planned.

“I always seem to be landing stuff,” he said. “But like, the Walker [Art Center] hasn’t been pleading with me.”

Dale explains that he’s about to ship an eight-foot winged angel that looks like Nefertiti in a white night dress. It’s going to a private Christian school in New York for their prayer chapel. His son helped him attach the hinged wings.

“This is like what I think maybe an angel is,” Dale said. “But I think they might be just men, or maybe they’re women. I never figured out that.”

Artist Dale Johnson’s “angel” in his St. Paul studio on March 28, which will soon be shipped to New York.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News

Karen washed dishes in the kitchen, a tiny space with a tiny fridge where grandkid art was held up with magnets. Through the kitchen behind her was a door to the hallway of the former Colonnade Hotel. The hallway was done in richly patterned carpet, emitting the odor of generations of smokers, which led to a lobby with more than one crystal chandelier.

This is where Dale brings his art so he can really get a good look at it.

‘He’s a painter’

A neighbor passing through to the elevator called out, “He’s a painter,” and the doors closed behind him.

Back in the apartment, the gray kitty Rascal laid on the couch beneath the painting of Lake Michigan. Karen said they are preparing to return to their lake cottage in Grand Haven, where they spend six months of the year.

Rascal at Dale Johnson’s artist studio and home in St. Paul on March 28. Rascal is a cat Karen Johnson said they picked up from an estate sale.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News

They met there 60 years ago. Dale lived in Grand Haven and Karen was summering with her parents and they attended the same church.

“We winter in St. Paul,” Dale said, dryly.

Dale held open the door to the sidewalk. I asked if he wrote the “love” and “joy” on the column bases. “Mmhmm,” he said.

And the Roman sculptures? No, they belong to the building.

“They’re kind of weird,” he said.

A painting of the Colonnade Building at Dale Johnson’s artist studio and home in St. Paul on March 28.

Alex V. Cipolle | MPR News