It’s both ironic and bittersweet that broad interest in and admiration for Shaker art and culture—which marks its 250th anniversary in the US this year—has been steadily growing over the years and is at a high, even as the population of the group has dwindled close to zero.

According to a recent report in the New York Times, only two Shakers remain; they reside at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in New Gloucester, Maine. The community, described as the longest-running Utopian experiment in the US, embraced communal living, simplicity, and celibacy (the latter because they didn’t believe in procreation and sought to emulate Jesus).

For years design aficionados and others have admired and sought their famously minimalistic and well-crafted furniture, remarkable for its clean lines. Now two well-received New York museum shows that opened almost simultaneously last month, are delving further into the art and culture to shine a light on lesser-known practices and aspects of Shaker life.

The first is “Anything But Simple: Gift Drawings and the Shaker Aesthetic,” a show of elaborate and intricate “gift drawings” at the American Folk Art Museum near Lincoln Square, that was years in the planning and originated at the Hancock Shaker Village in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in 2022. Gift drawings, made by mainly untrained Shaker artists, record spiritual visions, referred to as “gifts” in Shaker culture.

Polly Jane Reed, A Type of Mother Hannah’s Pocket Handkerchief New Lebanon, New York (1851).

Andrews Collection, Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts,Also on view is “Cradled,” which was jointly curated by actor Frances McDormand and conceptual artist Suzanne Bocanegra, who teamed up with the Shaker Museum in Chatham, New York, for this thoughtful show that examines the community’s lifetime approach to caring for and providing comfort to individuals right up until their death. It’s on view at the Kinderhook Knitting Mill in Kinderhook, New York. Both shows are fascinating in their revelations and have some interesting overlaps in terms of approach, and organization not to mention the obvious reverence of Shaker culture and life.

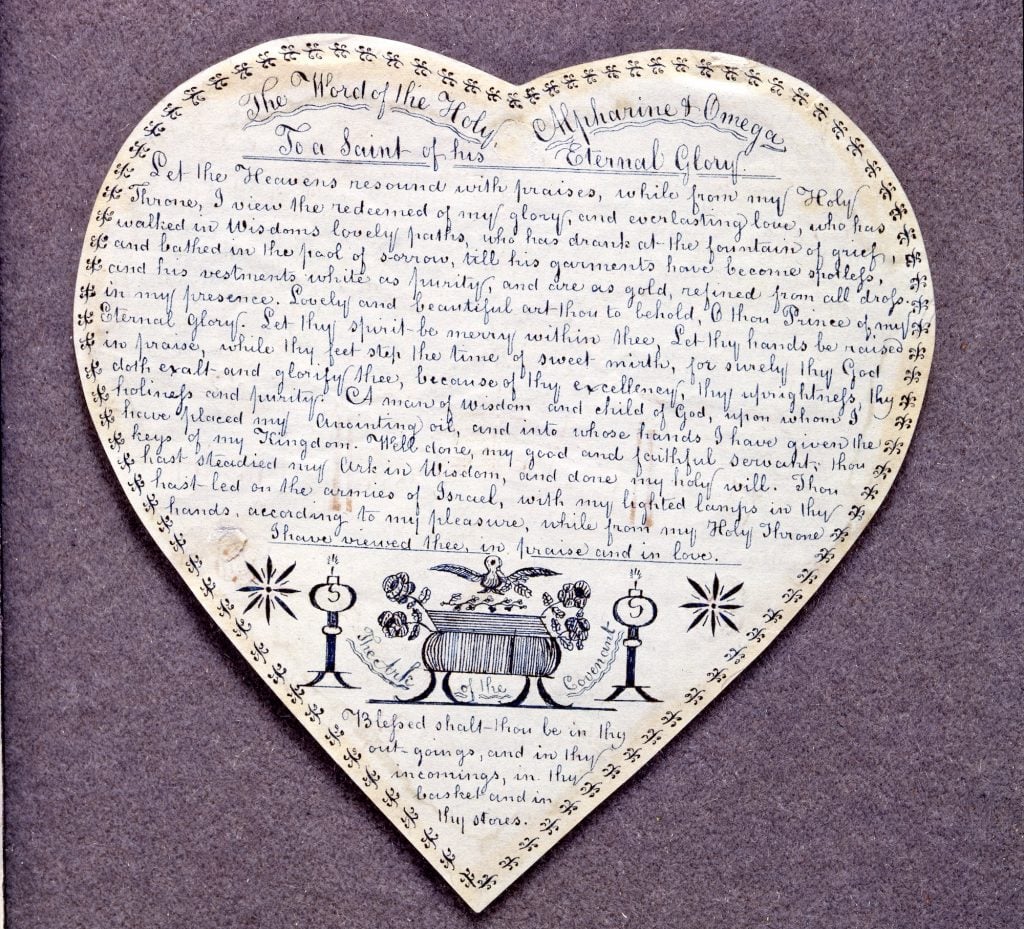

At the Folk Art Museum, the “gift” drawings on display “represent a departure from the simplicity typically associated with Shaker material culture,” according to a statement. These works, made by women in the mid-19th century, are believed to represent divine messages and are filled with intricate texts and symbols that offer a unique glimpse into their interior world.

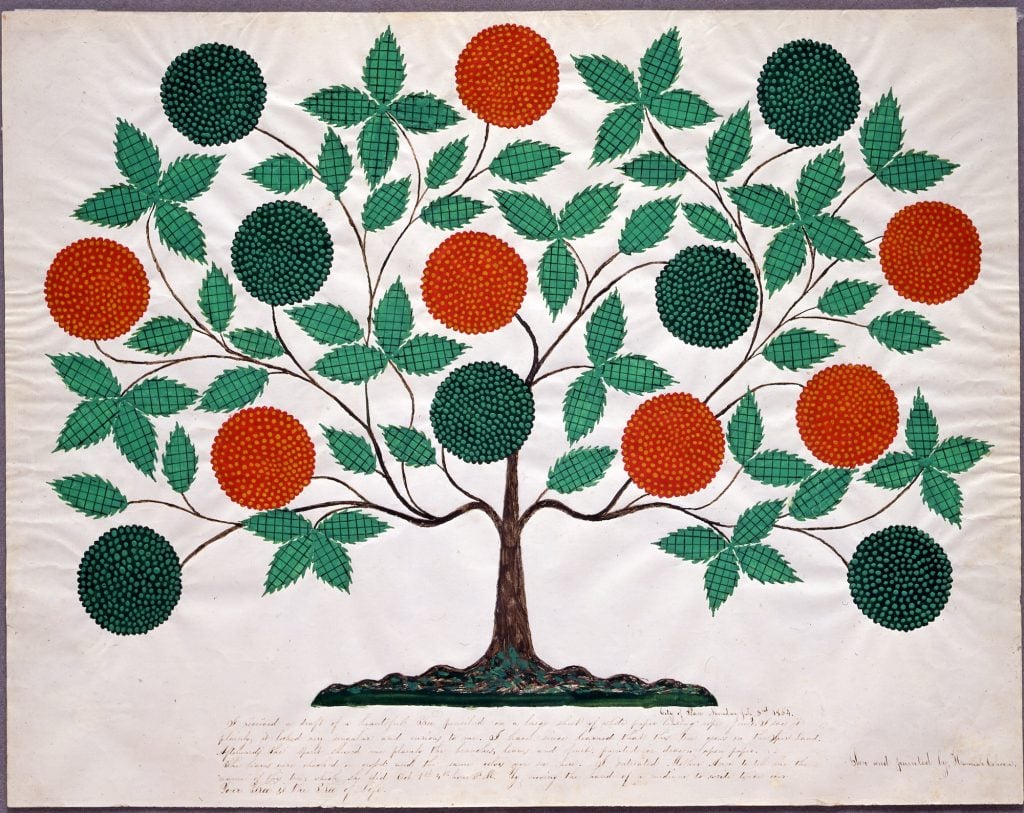

“Most people have not encountered these drawings. It’s interesting how structured these are even though they’re meant to represent the celestial world and are representative of the heavenly sphere that is not accessible when you’re on Earth,” said Emelie Gevalt, a curator at the Folk Art Museum and curatorial chair for collections, in a phone conversation. “They are also very controlled. You see that proclivity for structure and careful planning seen in other Shaker material,” she noted.

Polly Jane Reed, Heart-shaped Cutout for Rufus Bishop, New Lebanon, New York (1844)

Andrews Collection, Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts,

Gevalt estimated that only about 200 of these drawings may still be in existence. Others may have been destroyed out of concern or apprehension about their interpretation by outsiders. The intentions of the drawings—and whether they were meant to be exhibited—remain a matter of debate. Gevalt pointed out that the last major exhibition of gift drawings, which took place at the Drawing Center in downtown Manhattan in the early 2000s, included a photograph of one of the Shaker elder sisters, shown sitting in a living space with a framed gift drawing visible on the wall behind her.

“There’s a lot of discussion about visuality in the Shaker community,” said Gevalt, “In the way that you see these essentially all-text versions of the drawings, like leaf or heart-shaped ones, in some ways, it’s the purest or simplest manifestation of a gift drawing where its primarily text but then the shape becomes part of the gift itself.”

Gevalt also emphasized that the works were primarily executed by women, which is notable considering the works were made in the 18th and 19th centuries when women were not typically “given center stage.”

While it’s undoubtedly a spiritual show, she noted that the Shakers were also dedicated to the idea that “even the more mundane of daily activities could represent prayer, akin to what we might call mindfulness or grounding nowadays.”

Suzanne Bocanegra, Joan Jonas, Annie-B Parson at “CRADLED,” at Kinderhook Knitting Mill. Photo by Matt Borkowski, BFA

Similarly, in a phone interview with Bocanegra and McDormand, Bocanegra shared that her interest in Shaker culture dates back to at least the early aughts when she saw the aforementioned Drawing Center show.

“The way that they’re put together, and even though they’re very complicated and detailed, they’re very symmetrically laid out,” said Bocanegra. “This whole idea that the drawing is a gift and it is not owned by anyone, it has to walk this fine line with the Shaker religion.”

Along with being a longtime admirer of Shaker Furniture, McDormand developed a performance piece with the Wooster Group a few years ago titled “Early Shaker Spirituals” based on a recording by Shaker women that had been passed down through successive generations via an oral tradition. Earlier, in 2005, McDormand acted in a Shaker-focused project that dancer Martha Clarke created.

Of the Kinderhook show focus, which was inspired in part by research of the Shaker Museum archives, McDormand said she loved “the idea that they built something that could hold an infirm or elderly person, who was bedridden, and that it was a communal act of giving to rock them and comfort them.”

“As a piece of furniture, the cradle has to involve other people,” said Bocanegra. “One person is in it, but it has to be activated by another person, otherwise it doesn’t work.”

“Bertha” Shaker dolls with custom-designed clothes at “CRADLED” at the Kinderhook Knitting Mill. Photo by Matt Borkowski/BFA

Adding another layer of fascination to this thoughtful project, the two invited 88-year-old performance artist Joan Jonas, whose acclaimed MoMA retrospective wrapped this summer, to be part of the opening night celebration. Jonas agreed to be rocked in one of the adult cradles. McDormand and Bocanegra pointed out that there are more adult cradles in existence than child cradles, given the emphasis on celibacy and not pro-creating.

After McDormand and Bocanegra came across some dolls in the archives and found that the Shakers made doll clothes for their catalogues, along with the many other products they sold, “we commissioned a seamstress in Columbia County who make ‘limited edition’ ensemble and hangars.” So far they have sold seven of them, and are planning to auction another to raise funds for the Shaker Museum. The dolls are called “Bertha” dolls but they bear a striking resemblance to another iconic doll, famous for her love of pink, and whose name also begins with a “B.”

Hannah Cohoon, The Tree of Life (1854).

Andrews Collection, Hancock Shaker Village, Massachusetts, 1963.117

The Shakers were interested in creating beautiful, aesthetically pleasing, and excellent artifacts,” says McDormand. “And they were also very much selling everything. Making money was for the good of the community. They were really successful that way.”

As for “Cradled,” the show has just been extended until December 6 and there is a good chance that the show will travel to another venue. Stay tuned.