The first word that Pablo Picasso ever pronounced was “pencil.”

At least that was how his mother remembered the young prodigy: that he drew before he could speak, and that the word “piz” — short for “lápiz,” or pencil in Spanish — was the first sound he ever made.

That’s because young Pablo grew up in the atelier of his father, José Ruiz Blasco: an academic painter, art teacher and restorer to whom he was apprenticed when he could barely walk and whom he quickly emulated.

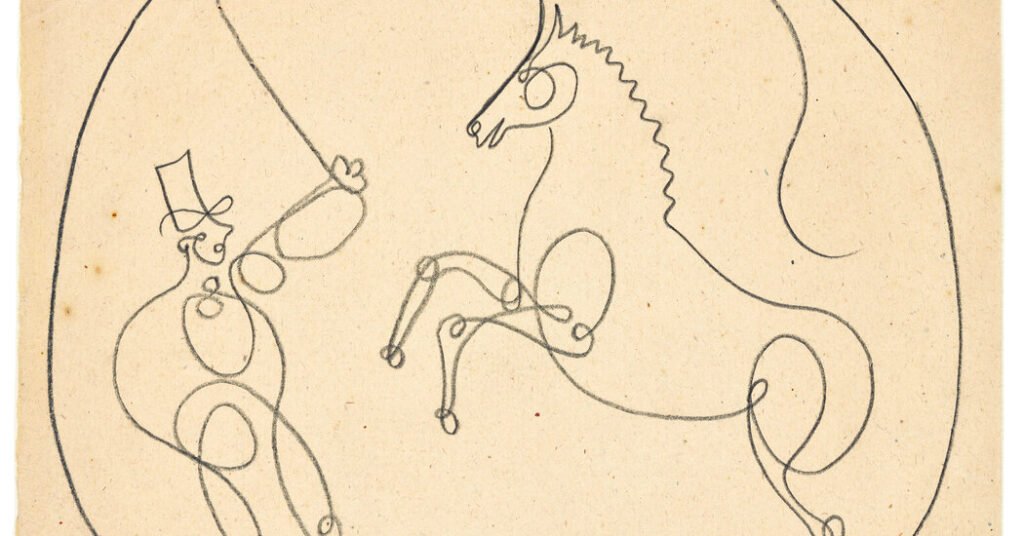

Fifty years since the artist’s death at the age of 91, the Pompidou Center in Paris is paying homage to Picasso the draughtsman. Nearly 1,000 works — notebooks, drawings and engravings, most of them borrowed from the Picasso Museum in Paris — will be on show in what is billed as the largest-ever retrospective of the Iberian master’s drawings and engravings. The exhibit, “Picasso: Endlessly Drawing,” runs through Jan. 15.

To Anne Baldassari — one of the world’s foremost Picasso scholars, who spent 23 years at the Picasso Museum as curator, director and then president, leading the museum’s redevelopment — drawing was not just a quick preparatory pursuit for Picasso; it was an end in itself, and at the very core of his art, a discipline that came before all else. And he was supremely good at it.

In a recent interview, Ms. Baldassari (who was not involved in the Pompidou exhibition) spoke of Picasso’s childhood in his father’s atelier, the fundamental importance of drawing in his work, and the exaggerated contemporary focus on his private life. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Was the word “pencil” the first word Picasso ever pronounced, as his mother recalled?

Given the importance and the singular place of drawing in Picasso’s work, this maternal anecdote would appear to be true. We know that Picasso drew before he could even speak. At school, he was a very bad student. He wouldn’t talk or write and spent his days drawing in the margins of his textbooks. The Picasso Museum in Barcelona has a few examples in its collections.

His first works, produced in La Coruña when he was merely a child, were little notebooks filled with jokes, riddles and stories destined for his family, which he drew on sheets folded in half.

How important is drawing in the work of Picasso?

Drawing is the absolute epicenter of his artistic practice. It is his primary means of expression. Painting and sculpture come second, as a way of synthesizing solutions that have been conceived and tested in the laboratory that is drawing.

In a word, drawing is his mental laboratory.

Painting and color never overtake the pictorial process completely in Picasso’s work. Drawing is used to test a concept, an idea, a theme, and once these are sharply defined and clarified, Picasso produces the end result in paint. Sometimes the drawings are produced in large format, so there’s not even necessarily a change of scale from drawing to painting.

What I’ve come to realize after 30 years of research is that the pictorial output of Picasso basically consists of drawings rendered in paint. His entire oeuvre is conceived, anticipated and elaborated through drawing.

Can you describe the atmosphere in his father’s atelier, where he was apprenticed as a very little boy?

Picasso’s father was an academic painter who often had to paint pigeons and doves, so little Pablo was in charge of making sure that these pigeons and doves wouldn’t fly off. He fed the pigeons and attached them to panels to stop them from moving during the sitting, because his father had to be able to paint them.

What is also extremely important, and not widely known, is that during these years of apprenticeship, young Pablo was in charge of making paper cutouts, painting them in different shades and tones, and pinning them to his father’s canvases so that his father could see what effect the different tones would have on the final work. This ancient studio technique, which Pablo mastered from childhood, would go on to form the basis of the Cubist revolution.

Picasso was also famous for drawing with just about anything.

Absolutely — with anything, and in any old way. That was the essence of his creativity and freedom, which were part of a never-ending process: Picasso never stopped.

My dear friend Claude Picasso, his son, who recently passed away, often laughed and marveled at his father’s haphazard ways. He said Picasso would draw with whatever he laid his hands on: pencil, crayon, charcoal, red chalk. He would cut pieces of wood and dip them in ink, paint, coffee, grease, anything he could find, when he had the urge to draw.

In this anniversary year of Picasso’s death, there is a lot of discussion around his treatment of the women in his life. He is being re-examined in the light of the #MeToo movement. What are your views on that?

There has been talk of Picasso and women for a long time. It is important to understand that painting is a language.

People say that his painting “The Weeping Woman” represents his lover Dora Maar, who has been mistreated by him. The reality is that at this time, the Spanish Civil War has just broken out, and Dora Maar is the face and representation of pain: a mask that is crying out with hurt. What Picasso is seeking to do is to mourn the dead of the Spanish Civil War.