I thoroughly enjoyed visiting the recently-concluded “In/Of Goa: Souza at 100”, an exhibition of the artworks of the celebrated Goan artist Francis Newton Souza (1924-2002), on the occasion of his birth centenary at Sunaparanta Goa Centre for the Arts.

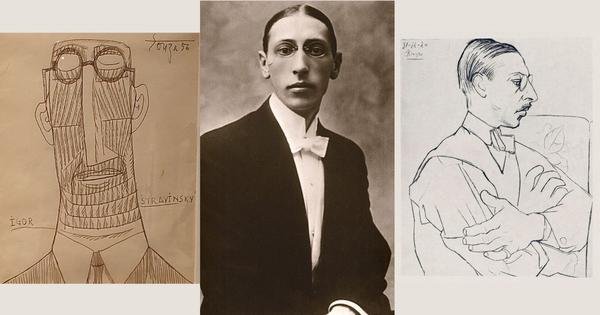

The exhibition aimed “to shed light on the profound influence of Goa, Souza’s birthplace, on his artistic journey” and it succeeded well in that objective. One work that seemed almost an outlier of sorts was an A3-sized pen-and-ink drawing titled simply “Igor Stravinsky” and signed “Souza 56”.

The collection had loads of nudes, of course, and self-portraits and landscapes. But there were just three named portraits of men: one, also in pen-and-ink of St Francis (the “other” Francis!) Xavier, another of British artist, writer and photographer John Rivers Coplans (1920 -2003), Souza’s contemporary and friend. These two have an obvious link to Souza. But why Russian composer and conductor Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1881 -1971)? Souza was well-known for his eclectic taste in so many spheres, which would have included music. But as far as I knew, there was no documented affinity for this specific composer or his work.

In his extremely interesting and informative lecture “An introduction to the live of FN Souza”, Conor Macklin, director of the Grosvenor Gallery London, (which boasts on its website of “close ties with the artist and always endeavour to have a range of his work at the gallery”) had told us some entertaining stories about Souza in general and about some works in particular. After he had led the gathering on a walk-through of the exhibition, I asked him about the Stravinsky portrait. There was no specific anecdote, he said, apart from an obvious admiration Souza must have had for him.

I went home and tried to investigate further. I came across this on the Saffron Art, a co-sponsor of the Sunaparanta exhibition, and “a leading international auction house, and India’s most reputed, with over four hundred auctions to its credit. Its flagship gallery is in Mumbai, with offices in New Delhi, London, and New York”:

“Known for the highly critical and frequently disfigured portraits of clergymen and members of the upper echelons of society that he painted in the 1950s, it was very rarely that Souza created an image in appreciation of someone. The present lot, a portrait of the revolutionary composer and pianist Igor Stravinsky, seems to be one of the exceptional works that was borne of the artist’s admiration rather than his unsympathetic disgust. Created shortly after his seminal 1955 series of drawings, Six Gentlemen of our Times, this portrait also exemplifies the artist’s intricate cross-hatching and confident line. Although Souza has constructed Stravinsky’s features with his characteristic cross-hatching and the subject’s bespectacled eyes are placed high in his forehead, the face in this drawing is not that of a ‘soulless’ socialite or corrupt businessman, nor is it “a ridged, rocky terrain bounded by lines and petrified by its own violence” (The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2001, p. 83). Rather, in Souza’s portrayal, the composer comes across as an intelligent individual, held in high regard by his peers.”

All very interesting, but no clear reason for Souza’s “appreciation” of Stravinsky. But there is plenty of room for an educated guess, or perhaps many.

Stravinsky, especially after the scandalous 1913 Paris premiere of his revolutionary ballet Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring) was labelled the “enfant terrible” of classical music of his time. The famous auction house Christie’s called Souza the “enfant terrible” of Modern Indian art.

The enduring formative impression of Roman Catholicism in Souza’s Goan childhood on his art is well-documented. Yashodhara Dalmia, in the chapter A Passion for the Human Figure: Francis Newton Souza of the above-mentioned book The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives, quotes him extensively on the subject.

Although Stravinsky drifted away in his adult years from the Russian Orthodox Church he had been born into, his homesickness while in Europe drew him back to the faith, “a portable piece of Russia”. An especially moving ceremony at the Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua in 1926 while on a concert tour made him formally rejoin the Church. A slew of sacred compositions followed, most famously his Symphony of Psalms for chorus and orchestra (1930, rev 1948) and Canticum Sacrum for tenor, baritone, chorus and orchestra (1955).

Souza and Stravinsky also had inspirational subject matter (in addition to Christianity, of course) that overlapped. Oedipus Rex, based on Sophocles’ tragedy, was a Stravinsky opera-oratorio (1927). The inspiration for Souza’s 1961 depiction of the tragic king was (as he himself explained) his own irrational feeling of guilt that his father died soon after his birth, and the disturbing revelation of surreptitiously watching his mother bathe through a hole he bored in the door. Imagine what Freud (Sigmund, not Lucian) would have made of that! It certainly puts his obsession with the female anatomy in perspective.

Macklin spoke of Souza’s strong anti-nuclear testing sentiment in the late 1950s and early 1960s as the motivation for his 1961 painting Apocalypse. Plans in 1953 by Stravinsky and Welsh poet-writer Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) to collaborate on an opera which detailed the recreation of the world after one man and one woman remained on Earth following a nuclear disaster never materialised with Thomas’s sudden death. Stravinsky instead completed In Memoriam Dylan Thomas, a piece for tenor, string quartet, and four trombone the following year.

Stravinsky was the subject for many other artists, from Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861 -1942) to Robert Delaunay (1885 -1941) and several others, but most famously Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

The most plausible link between Souza and Stravinsky could have been Pablo Picasso whose timeline as you can see neatly overlaps that of Stravinsky. The friendship between Picasso and Stravinsky was strong, and even got them arrested once for “drunken behaviour”. Stravinsky wrote a five-bar sketch of clarinet music for Picasso on a hotel telegram. He used complex rhythms, and also turned the telegram on its side so that the horizontal lines became vertical. This presented a new and surprising perspective on the familiar object whilst also physically cutting through his music. The piece, though barely a piece at all, explored Picasso’s Cubist ideas in a musical context.

Picasso responded with three sketches of Stravinsky in 1920, one of which was almost confiscated at the Swiss border on suspicion of being a coded military plan.

Picasso also drew the cover art for Stravinsky’s 1918 Ragtime and designed the costumes and sets for his 1920 ballet Pulcinella.

Dalmia mentions Picasso’s profound influence on Souza, as did Macklin in his lecture. Picasso himself once said, “Lesser artists copy, great artists steal.” An identical sentiment that has also been attributed to Stravinsky himself: “Good composers borrow, Great ones steal.”

Souza referenced Picasso’s 1907 Demoiselles d’Avignon (which itself was “inspired” by Paul Cezanne’s 1880 Bathers) with his own Ladies of Belsize Park (1962).

It is possible that Souza was responding to Picasso’s Stravinsky sketches with one of his own. A great “steal” if ever there was one.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa. It has been reproduced with the permission of the writer.

Also read: Artist FN Souza’s early works reveal his intimate connection with Goa and its people