While London was being rebuilt after the Blitz, Frank Auerbach began work on a series of charcoal portraits that would revitalise post-war British art. In keeping with his surroundings, he adopted a method of destruction and renewal, drawing his sitter’s features with rapid, heavy marks before erasing and redrawing them, over and over again, for months on end. Often seen to embody the austere atmosphere of their day, 17 of the drawings have been gathered by the Courtauld Gallery in London for the first exhibition ever devoted to them, seeking to reappraise their significance.

Drawing the people closest to Auerbach always produced the best results

“The exhibition’s focus on the charcoals is very much driven by the fact that Auerbach invented a new way of drawing,” says the show’s curator, Barnaby Wright. Auerbach’s method of applying and scraping off thick layers of paint is well documented, and it was during the preparation of a 2009 exhibition of the artist’s paintings that the idea came to Wright for a show of the drawings. “Working and reworking the drawings… I can’t think of a precedent in art history for them. They are a major contribution to the art of the period,” Wright says.

While Wright is keen to emphasise how the drawings were an end in themselves, the exhibition will also include six paintings from the same period selected to give an insight into the close relationship between these two strands of Auerbach’s work. The drawings and paintings of Auerbach’s friend and fellow artist Leon Kossoff, for example, share a similar tonal balance, while the monochrome oil-on-board Head of E.O.W. VI is painted with a draughtsman’s use of line.

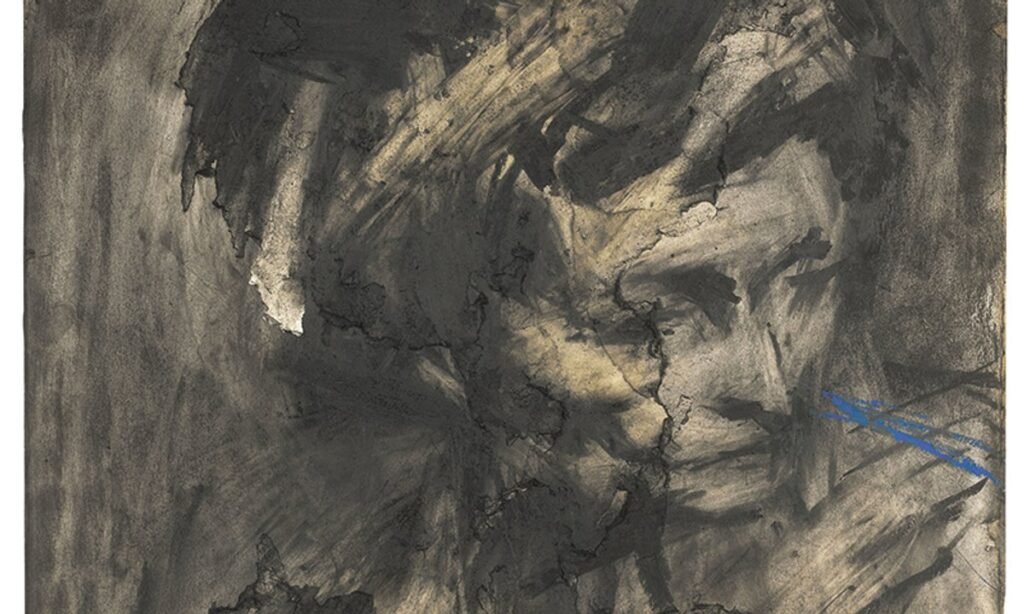

Auerbach’s charcoal and chalk drawing Head of Leon Kossoff (1956-57) © the artist; courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects; London

Alongside their formal innovation, the portraits are deeply personal. Born in Berlin in 1931, Auerbach was sent to England by his Jewish parents, who were later murdered by the Nazis. The only relative he saw again was his cousin, Gerda Boehm, of whom five portraits are included in this exhibition.

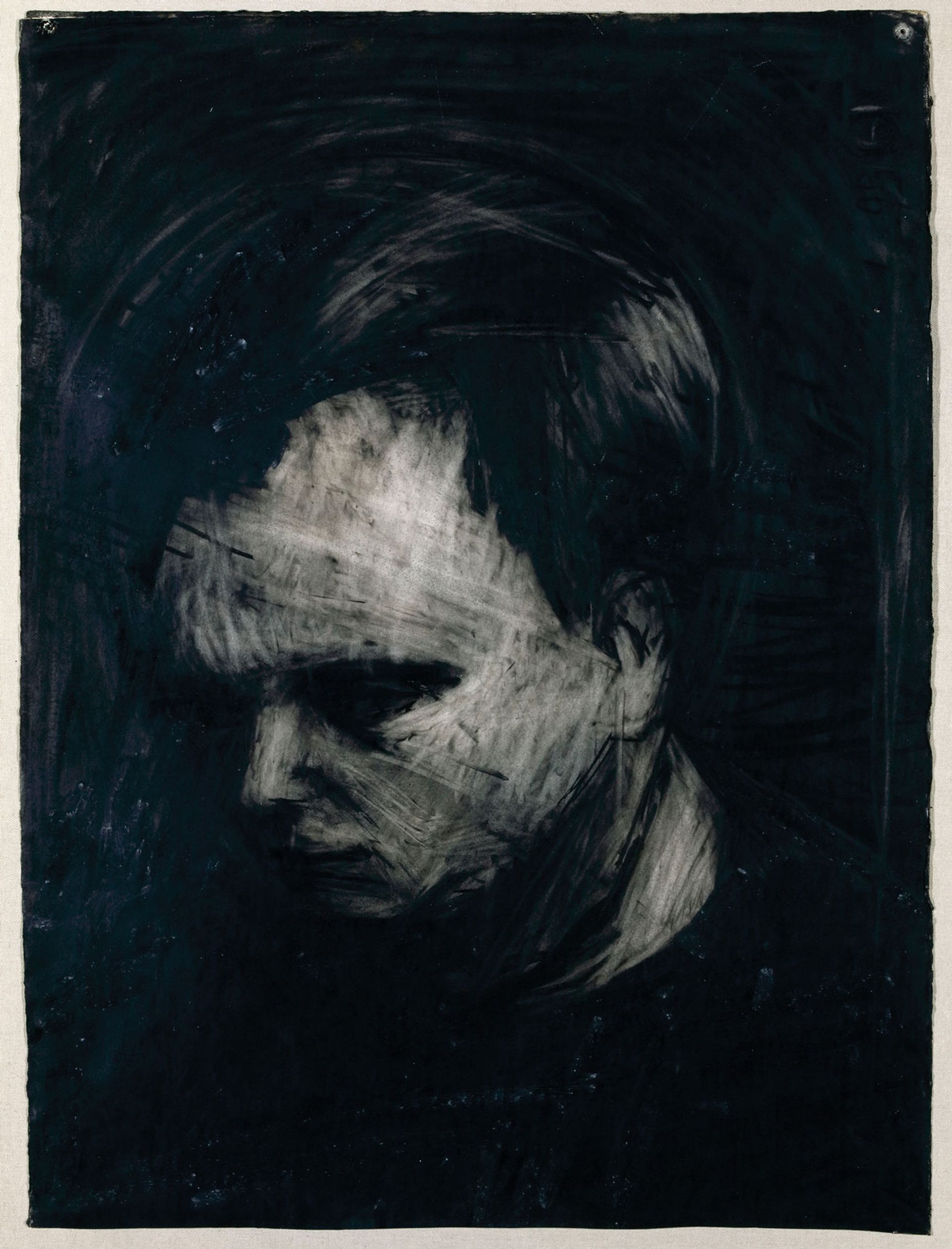

Drawing the people closest to him always produced the best results. The portraits of Boehm, Auerbach’s wife Julia, his lover Stella West, his friend Helen Gillespie, Kossoff and the artist himself record a pivotal phase in the life of an intensely private man. Auerbach still works in the same Mornington Crescent studio where many of these drawings were made, and his recollection of this time has played an instrumental role in the preparation of the exhibition, which has been the catalyst for new research. The findings are published in the catalogue, which also features an essay about Auerbach’s Self-Portrait (1958) by the Irish novelist Colm Tóibín.

• Frank Auerbach: the Charcoal Heads, Courtauld Gallery, London, 9 February-27 May