Lincoln, Neb. —The EPSCoR project Jessica Corman leads really picked up STEAM by incorporating art.

After seeing results from the first year of the project, the National Science Foundation quadrupled the art funds.

Originally, the team had proposed compiling data on aquatic ecosystems like lakes, streams and wetlands and their chemistry. The data could concern carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous in the water, bugs, plants and algae to gauge water quality and safety for drinking and wildlife. Corman had also proposed that a portion of the RII Track-2 award go toward work with an artist.

She said the “Art, Data, and Environments” portion of the award had the objectives to think more broadly about the data being generated and more inclusively about who would benefit from it. Katie Anania, a professor of art history, helped the scientists meet these objectives.

“The first step that she did was to have us have conversations thinking outside of our very familiar X-Y plots to think more broadly about how we could communicate data,” Corman said.

The group met at the Sheldon Museum of Art and viewed paintings and photographs of landscapes and Native American symbolism of the seasons and changes through time. They discussed how these artists represented environmental data.

“As soon as we introduced art activities at the Sheldon Museum into the grant, everyone on the project–from the PIs to the graduate trainees–started to look a little more closely at how they used visual material in their work,” Anania said.

She led workshops where the scientists looked at figures they had already published or hoped to publish to help communicate their data. Participants dug deeper into a figure meant to communicate changes in insect communities from before and after a hurricane in Puerto Rico. The team came up with a figure resembling a beaded bracelet and inspired by Aztec and Mayan Nepōhualtzintzin ways of tracking money or quantities in Central America. The lead on the insect project then presented his data using the figure at conferences and published an article in Leonardo about his experience using the figure.

After the first year, when the National Science Foundation awarded the team more funds for the art-science collaboration, Corman was able to offer fellowships to two other art historians, Jessica Santone and Dorota Bizcel. They brought in Vaughn Bell, an environmental artist from Seattle.

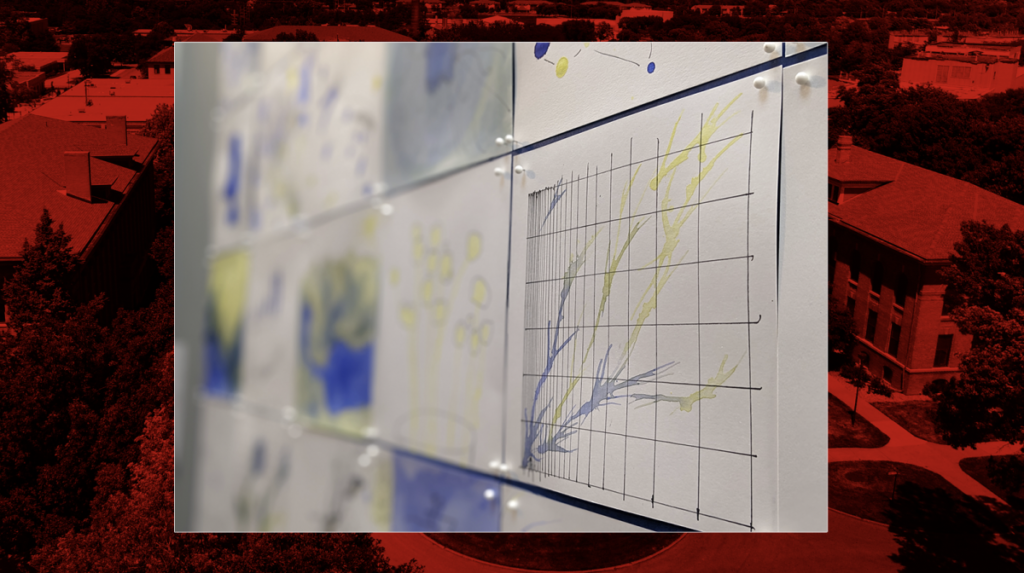

Bell led 70 scientists in exploring their scientific interests with art at an international conference on March 21, 2023. At the Conference on Biological Stoichoimetry, each participant received three 8X8 sheets of paper, watercolors in yellow and blue and pipettes to draw with.

Bell asked them to create three pieces of art with the prompts to make a grid and tell a story with water and science research materials, picture their workplace and draw it, and visualize their research and draw its process and results, noticing how their drawings portrayed time.

“It was a very different perspective than artists communicating the scientist data, but it was really the artist creating space for the scientists to create art of their data,” Corman said.

She drew the Niobrara River as her place of work and turned toward more abstract art to picture the process of research, which could be messy and convoluted, she said.

“We sort of talk about like ‘Oh, we go from observation to hypothesis to experiment,’ but in reality, the process of science is so much more complicated,” she said. “Something that we’re hoping to do with this project is to get scientists to remember that sort of messiness and complication that comes with doing your science, and that that can actually be a really wonderful way to engage people in conversations about the work that you’re doing.”

Corman said she was impressed by the creativity of the conference participants, who came from 18 states and five countries and ranged in profession from undergraduate students to National Academy of Sciences members.

“We were bounded by the prompts and bounded by the colors and the tools we could use, but it was just great as scientists to be unbounded in the way we could express our creativity in just a very different way than we normally do,” she said.

Most of the participants were scientists, but Corman said a representative from a Natural Resources District and one from Nebraska Game and Parks also took part. The five states involved in the project–Alaska, Arkansas, Nebraska, Vermont and Wyoming—already work with water quality managers, stakeholders and decision makers, but Corman said she thought it was important to include such people in the communication training and tools.

She said she especially tried to convey to the graduate students that communicating science is not just about finding the answer and handing that information over but about incorporating the people dependent on the body of water.

“Instead of just relying on, ‘Study is done. Here’s the results,’ you actually start building relationships and building trust with people, and that tends to lead to much better results at the end of the day,” Corman said.

A goal of the RII Track-2 program is to build capacity in states to carry out research. Corman said she thought the conference helped them meet that goal.

“Not only was this a really great intellectual exercise, but it was also a way to build the team and build connections between sciences,” she said.

After the conference ended, Santone and Bell selected 80 of the participants’ paintings and assembled them in a display at the Constellation Studios gallery in downtown Lincoln. The watercolors became part of a larger exhibit, “Approaching Water,” that drew 250 to 300 attendees.

A sound artist also put data from Corman’s Niobrara River research to music and played it in the background of the exhibit.

The team received many positive comments about both the conference and gallery, Corman said.

She stated the most important outcome for the project as “this idea that art is not just a tool to communicate science, but it’s also a tool that scientists can use to think about their science, to think about the process, and to think about who’s engaged with the science that they’re doing.”

She and Anania have already begun talks about ways they could include this idea in a training for graduate students.

And Corman signed up for a drawing course at the LUX Center for the Arts.

“I realized how poor my artistic skills were compared to some of my colleagues,” the project leader said with a laugh.