Photo Aubrey Mayer

Los Angeles–based artist Jonas Wood is best known for his paintings that feature landscapes, vessels, interiors, plants, and his love of sports. Recent exhibitions include “Henri Matisse & Jonas Wood” at Nahmad Contemporary in Gstaad, Switzerland, which displays both artist’s works in comparison, with a text written by curator and art historian Helen Molesworth.

But his drawing practice has been just as important to his development as an artist. Those works on paper the subject of his latest exhibition, “Drawings 2003-2023,” at Karma in New York (on view until August 18). One-hundred works on paper are displayed in chronological order in a salon-style format showcasing the artist’s wide breadth of subject matter, color, and mark-making. Bright and colorful, this show will also travel to Karma’s Los Angeles space in November 2023.

To learn more about his exhibition, ARTnews spoke with Wood by phone from New York. During the conversation, Wood spoke about his biographical roots, his trajectory through academia, the working world, and the advice that shapes his career and legacy. Wood also discusses the materials he employs and the process behind his vibrant body of work.

This article has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Jonas Wood, Studio Shelf, 2005.

Courtesy the artist and Karma

ARTnews: This exhibition focuses on your drawings from 2003 to 2023. Why did you want to focus on this 20-year timeframe?

Jonas Wood: Well, this July will be 20 years of living in Los Angeles as an artist, post-grad school. I created an installation of drawings from over the years. I am happy to work with [Karma founder] Brendan Dugan and Karma on this project. Brendan does such incredible historical shows, and I wanted to do something different. I have never exhibited a collection of only drawings.

There are a lot of people that work to find themselves after grad school. Can you tell me a bit about your life then?

I graduated from the University of Washington in Seattle in 2002. My wife, artist Shio Kusaka, and I briefly went to Martha’s Vineyard before moving to Los Angeles six months later. I asked myself, “Do I want to live in New York? Or do I want to live in LA?” So, I moved to LA because I had one friend there and started painting and drawing. I kept thinking, “How do I keep practicing? How do I get better?” Making drawings was a big part of that. I received excellent advice about how to keep working post-academia from a few of my teachers in grad school and how to practice outside their watchful eyes. When you’re in school, you have your peers and professors who observe and critique what you’re doing. My professors asked me, “What artists do you like? What did they paint? How did they practice?” I focused on the word practice to keep practicing painting.

From left, Jonas Wood: Momo and Shio at Huntington Garden (2023) and Shio and Robot (2008).

Courtesy the artist and Karma

What was some of the advice they gave?

My grad school professor Denzil Hurley, who died a couple of years ago, was incredible at activating young minds. He just had a show up at Canada Gallery in New York. He advised me to challenge myself because the University of Washington wasn’t a finishing school, like UCLA or all the great art schools in California, where the grad students are so exceptionally talented that they’re almost ready for the bright lights of gallery exposure. In Seattle, they focused on how to have an art practice and most likely apply to be a professor of art—teaching painting was more like a ceiling. The idea that you would be painting somewhere by yourself was more what I was focusing on. That was great advice, even in an atmosphere like Los Angeles, where many outstanding artists surrounded me. Also, the job I subsequently had when I first moved to L.A., assisting [artist] Laura Owens in her studio, paved my path.

How did that job come about?

I worked with Laura for almost a year and a half. The one friend that I knew in California was artist Matt Johnson, who is a fantastic sculptor. He and I went to high school together. Matt was already working for artist Charles Ray, and then he had taken a class with Laura at UCLA. After I was in LA for a couple of months, she was looking for an assistant and asked if some students were interested in the job. She asked some grad students if they were free, and Matt said, “I’m not. But my friend who just moved here is a painter.”

The first thing I was working on for her was a painting that she was making for the [2004] Whitney Biennial, and then, subsequently, in the weeks that followed, I realized who she was. Everybody was like, “You got that job?” But I just got lucky and met this unbelievable genius of a person. The learning experience was next level. I retained as much valuable information from Laura as I had learned in grad school. She painted a variety of things, which was liberating for me to discover, along with her mastery of drawing and painting. And in the mid-2000s, my wife worked for Charley Ray for almost four years, who is an extraordinary sculptor, so we both had great jobs.

From left, Jonas Wood: Wave Landscape Pot (2020) and Orange Bonsai in SK Dino Pot (2023).

Courtesy the artist and Karma

I was an assistant, too. My first job after UCLA was working for David LaChapelle. Working closely with someone like that makes you realize what it takes to be an artist. You said you and your wife decided to move to L.A. together. Do you bounce ideas off each other within your art practices?

I was focusing on making still-life paintings. Since Shio made all these vessels, it was natural that I was borrowing her objects and putting them in my pictures, just out of practice. When I had a solo show at the Black Dragon Society Gallery in 2006, and then one in 2007 at Anton Kern Gallery, people began asking me, “What are these vessels?” And I said, “Oh, these are my wife’s vessels.” She’s super supportive of me being a maniac painter, and we have been sharing a studio since 2005. We are not in the same room but working under the same roof. We have worked together for a long time, so we’ve been cross-pollinating and giving each other feedback and healthy criticism.

Regarding your drawing and being a draftsman, do you keep a sketchbook?

I don’t keep a sketchbook. I think of drawing as sketching with anything on paper, whether that be pen, watercolor, or colored pencils. I evolved to call it drawing, but only some call it that. For example, Laura Owens considers anything with paint on it a painting. I think about anything that is on paper as a drawing. I make a considerable amount of drawings to rigorously prepare my paintings or a detailed study that I use as a model to paint. When I paint, I paint a lot from sketches I’ve made. I read and try to interpret them in painting.

When a drawing translates into a painting, the image becomes more powerful in so many instances.

Right, drawing, personally, is facilitating how to make the best possible painting.

Jonas Wood, Bromeliad Still Life, 2021.

Courtesy the artist and Karma

You have such a wide breadth of objects and places in all your works, and I find that so enriching and thrilling to see. What you capture so well is the light in LA.

On the West Coast, it’s not just the light but also the people and how my life changed. I’m from Massachusetts, and the East Coast can be gritty and hardcore. While the West Coast is pretty laid back and sunny. When I arrived in Los Angeles, I noticed plants I had never seen and got into painting them. I was already in this mode of thinking, “How could I better myself?” and “How could I transcend my current situation as an artist?” I fell into the beauty of the space as a young adult. They all coincided.

L.A. was the first city I was happy to land in, and I felt I was coming home. The light is excellent for a studio, but I have always been obsessed with colors. I’ve always thought about how colors work together. And all those things collided with my interests and what I focused on in painting. All those things activate my mind.

I see a lot of sports references in your works. Where does that come from?

One of the things I was telling you, in the beginning, as the advice from one of my professors, is to pick subjects you’re genuinely invested in making. I’m a huge sports fan and played multiple sports growing up. I like the idea of athletes achieving or accomplishing something. It mainly started with practicing portraiture because I was sick of convincing a friend to let me take a picture and paint them. It is interesting to paint people you know, but it was like a different set of rules to paint somebody you didn’t know or idolize as someone who takes pictures or appropriates everything. I began to paint tennis courts, which came from photographs of turning the lights off and taking pictures of my TV during tennis matches and loving how it looked.

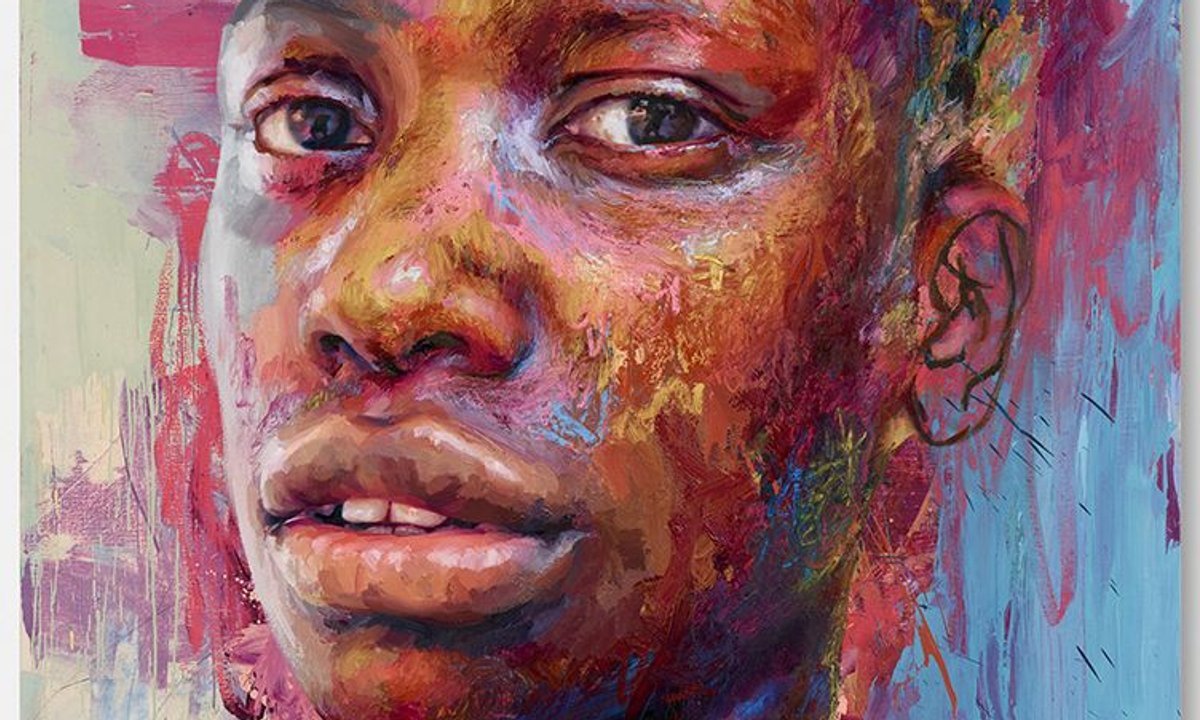

From left, Jonas Wood: Bo Jackson #2 (2018) and Larry Bird (2007).

Courtesy the artist and Karma

Oh, that’s so awesome. I love that it came from an everyday moment in your life.

In the tennis courts, it’s more about composition, abstraction, and repetition. The floating basketballs, tennis balls, or anything else makes me happy. I paint things I enjoy: plants, interiors, portraits, sports, and landscapes. All those things fascinated me from day one, and then I succeeded with it in the studio and continued pursuing it.

I think it’s sincere that you have kept a focus on subjects that you are genuinely passionate about.

Yeah, nobody had any expectations for me when I moved to LA, so I could do whatever I wanted. Second, I always thought of painting as needing to be more accurate. I’m a figurative painter who paints things from life, but I’m not a photorealist. I’m more like an abstract painter in that a painting could be anything. I didn’t cave into collector interest or curator interest. And I’m glad I didn’t have any success the first three or four years that I was in LA, so I could establish my identity without having too much feedback. I felt more comfortable with the idea that painting could be a variety of things not defined by one type of painting or one look, and I was very conscious of not wanting to get pigeonholed when I was younger. I intentionally showed a variety of motifs working together all the time, and I still do.

Installation view of “Jonas Wood: Drawings 2003–2023,” 2023, at Karma, New York.

Courtesy the artist and Karma

What type of materials do you use? Artists, I’m sure, would love to know.

I use a lot of light wash and watercolor as an underpainting. And usually, that’s Windsor Newton, or sometimes it’s a little bit nicer. And then, for colored pencils, I love Prismacolor.

Do you have the giant Prismacolor set?

I mean, I have every flavor under the sun of Prismacolor and anywhere in between—honestly, every color they’ve ever made. And some of them they don’t make anymore, so I have to find deadstock.

For oil paint, I like to use Gamblin, and for acrylic paint, I like Nova Color. I paint primarily on canvas or linen, and I use a certain kind of paper that doesn’t wrinkle or wave, no matter how much watercolor you put on. It’s the heaviest hot press-like watercolor paper you can get, almost like cardboard. I get it shipped from a French company as a giant piece of watercolor paper, 61 by 40 inches. (I don’t want anybody else to know the name so they don’t steal my paper spot.) I either make something that big or cut it down. I trace many things onto transparencies and project them because I still use an old-school projecting device and take photos, and I trace parts of the pictures and seam them together to make a particular image. On this trip to New York, I brought a couple of little notepads if I wanted to make some sketches, and then I bought some transparencies to trace.

Installation view of “Jonas Wood: Drawings 2003–2023,” 2023, at Karma, New York.

Courtesy the artist and Karma

As a final question, what does it mean to be showing all these drawings in New York?

It’s fantastic. I can’t wait for people to see this show. It’s immersive and compelling. My wife told me last night that if people have followed my work for the previous 20 years, they probably have seen all the works in the drawing show. Almost all of these works in this drawing show have been seen in the form of a painting. At a minimum, 60 drawings have all been made into paintings. I’ve had drawings sprinkled in my shows or in a room full of drawings, but I’ve never really had it as the primary focus. So, I’m eager to share this because it is the backbone of my studio practice.