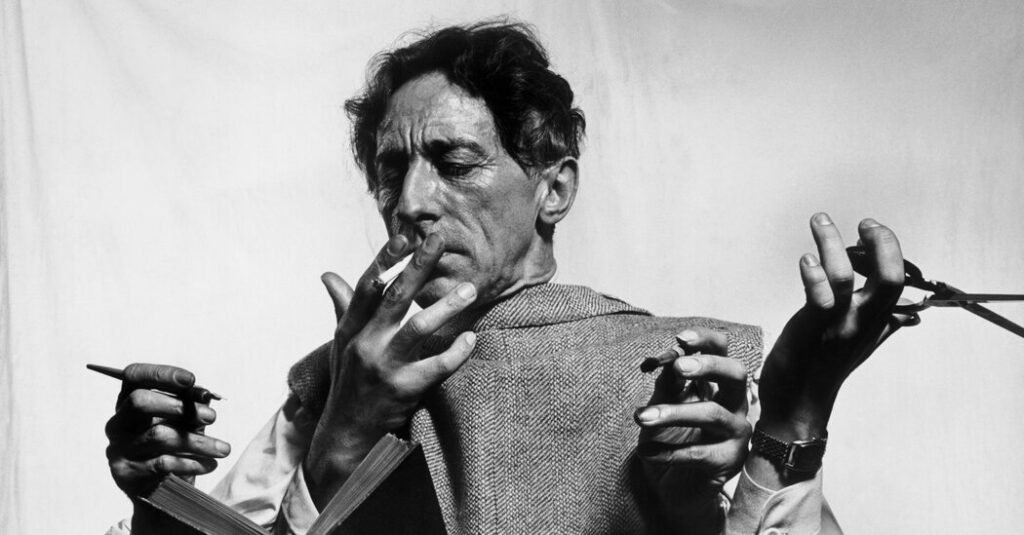

A 1949 photograph of Jean Cocteau, shot by Philippe Halsman for Life magazine, playfully depicts the suave and influential Cocteau, a leading figure of the 20th-century French avant-garde, with a surreal number of hands, holding a pen, a paintbrush, scissors, a book and, of course, a lit cigarette.

That image, now on posters all over Venice, beckons passers-by to the exhibition “Jean Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge,” at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection through Sept. 16. The show highlights the dexterity of the multitalented artist, writer, filmmaker and jewelry and fashion designer working fluidly across different media.

“Cocteau had kind of a bad rap as a dilettante — that accusation has haunted him,” said Kenneth E. Silver, a historian who organized the show with Blake Oetting, one of his doctoral students at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. “Moving all over the creative map is a given with artists now, but Cocteau was doing it almost before everybody else.”

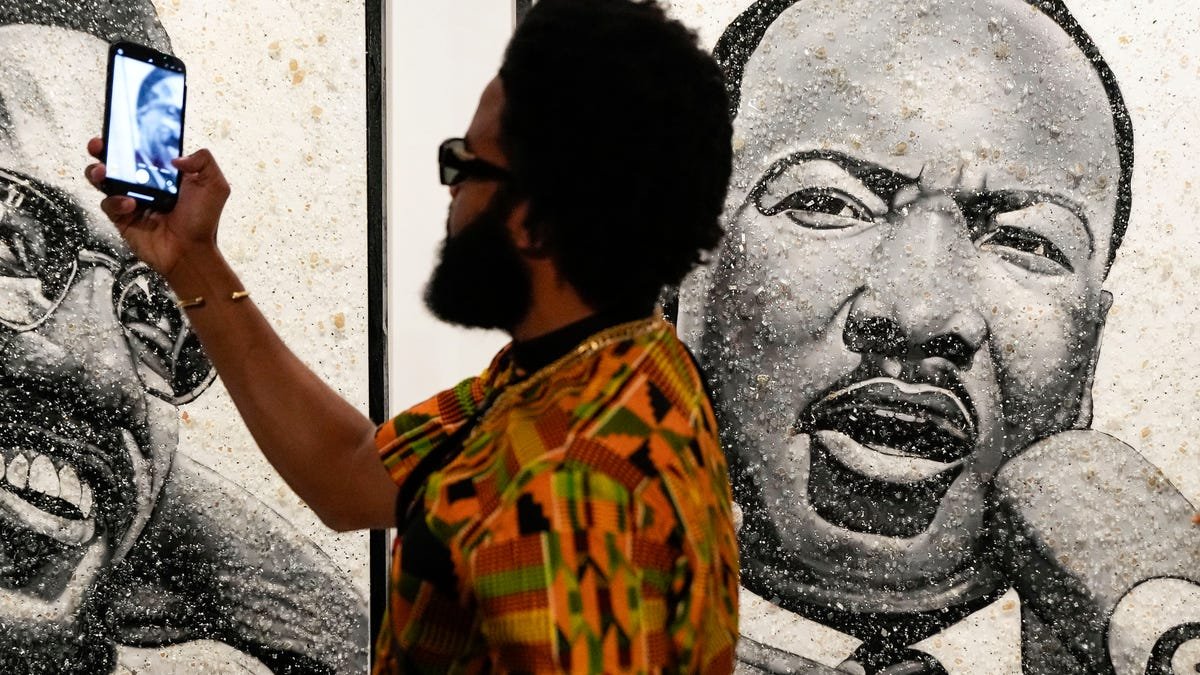

The museum’s curatorial team offered guided tours of the exhibition last week to participants of the Art for Tomorrow conference, an annual event founded by The New York Times and convened by the Democracy & Culture Foundation; it took place in Venice this year and focused on the theme of imperfect beauty. with panels moderated by Times journalists.

Perhaps best known for his 1929 novel “Les Enfants Terribles” (“The Holy Terrors”) and the 1946 feature film “La Belle et la Bête” (“Beauty and the Beast”), Cocteau was also a gifted and prodigious draftsman. Over the years, he produced nimble portraits of many in his circle, including Picasso and Elsa Schiaparelli (with whom he collaborated in 1937 on the design of a brooch in the shape of an eye with a teardrop pearl). All of these works are represented in the show.

The exhibition also underscores the story of Cocteau’s queerness through his frank drawings of nude men in moments of easy intimacy (the artist neither hid his sexuality nor ever came out). “Cocteau was not afraid of subjecting the male form to the same sorts of eroticized gaze that female models are so often subjected to,” Oetting said. The last major Cocteau exhibition, in 2004 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Oetting added, took place in “a different art world vis-à-vis questions of identity than we’re in now.”

Indeed, Cocteau’s experiences as a gay man, and as a crossover figure between the Parisian establishment into which he was born and the avant-garde, resonate with the exploration of outsiders broadly in the 60th International Art Exhibition at the Venice Biennale titled “Foreigners Everywhere,” organized by Adriano Pedrosa and on view through Nov. 24.

This alignment is serendipitous, but, according to Karole Vail, the director of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection and a granddaughter of Peggy Guggenheim, the connection is “total happenstance.”

Vail had the initial idea for the Cocteau exhibition, the largest ever in Italy, with more than 150 works by and of him, several years ago (before Pedrosa was named curator of the Biennale). She was interested in exploring the friendship between the artist and her grandmother, who inaugurated her first gallery, Guggenheim Jeune, in London with a show of Cocteau drawings in 1938, on the advice of their mutual friend Marcel Duchamp.

In her 1979 memoir “Out of This Century: Confessions of an Art Addict,” Guggenheim recounted: “The arrangements for the Cocteau show were rather difficult. To speak to Cocteau, one had to go to his hotel in the Rue de Cambon and try to talk to him while he lay in bed, smoking opium.”

Cocteau would eventually send her drawings of costumes and furniture he designed for his 1937 play “Les Chevaliers de la Table Ronde” (“The Knights of the Round Table”), and an enigmatic allegorical drawing in graphite, chalk, crayon and blood on a bedsheet he made especially for Guggenheim’s exhibition, called “Fear Giving Wings to Courage.”

The large-scale composition included a portrait of Cocteau’s longtime lover, the actor Jean Marais, with a fiery flock of hair and dressed in mesh tank top and shorts amid several nude figures, and it got held up in British customs because of the pronounced depiction of pubic hair.

Guggenheim could only get the piece released by promising to hang it in her office, shielded from the public, and she liked it so much in the end that she bought the drawing. “It did provoke a scandal,” Vail said, “and in some ways put Peggy’s gallery and her, ultimately, on the map.”

Cocteau, who fell in love with Venice at 15, would come to the city after World War II until his death in 1963, visiting Guggenheim at her home in the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal, now the site of the museum.

The exhibition there, in the palazzo, displays numerous drawings by Cocteau of gondoliers and Venetian cityscapes, as well as a letter he wrote to Guggenheim around 1956 (lent from Vail’s personal collection), illustrated with an affectionate caricature of her in a big hat. The show also includes a 1956 photograph of Cocteau on the roof terrace of Guggenheim’s palazzo and wearing a pair of her eccentric sunglasses, believed to have been shot by Guggenheim herself.

“Fear Giving Wings to Courage,” on loan from the Phoenix Art Museum, where it ended up after Guggenheim eventually sold it to an American relative, now is the big star, the 5-foot-by-8-foot sheet hanging on its own wall in the exhibition.

“The work is finally able to be seen in all its glory,” Oetting said, noting how Marais’s styling looks similar to that of gay men walking around downtown New York today. The story behind this work, he added, “is so indicative of the way that Cocteau himself has sort of been held up in the back office of modernism.”