As curator Denise Fong explains, these symbols of waste and urban decay exist in many places, and the Museum of Vancouver has worked with students at the nearby University of British Columbia to adopt Yao’s approach to grass-roots activism and to look at abandoned public space in Vancouver.

Born in Taiwan in 1969, Yao is the son of Yao Dong-sheng, a lawyer, legislator and traditional Chinese painter.

As part of the first generation of artists to emerge after martial law ended in 1987, the younger Yao was keen to break free from conventions and forge new forms of expression. “I hate traditional Chinese paintings,” he says.

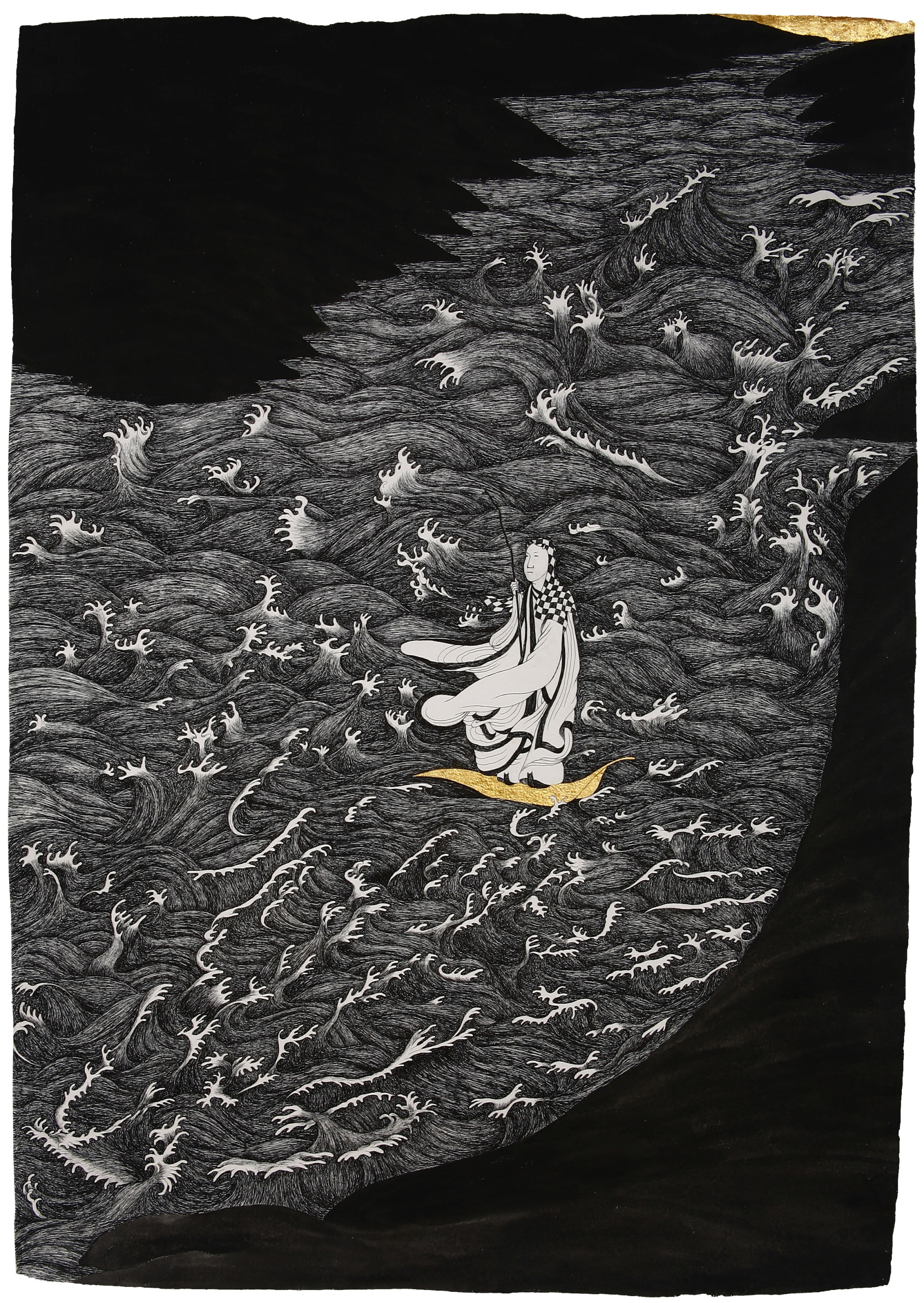

After his father died, however, Yao started making Chinese paintings, but on his own terms.

Yao represented Taiwan in the 1997 Venice Biennale, and has also been chosen for many major international exhibitions, including the 2018 Shanghai Biennale.

In 2007, when he was the artist-in-residence at Glenfiddich Distillery, in Scotland, he began to make so-called fake Chinese ink paintings with a ballpoint pen and gold leaf on paper. These types of projects, he says, help to fund his social projects such as the “Mirage” series.

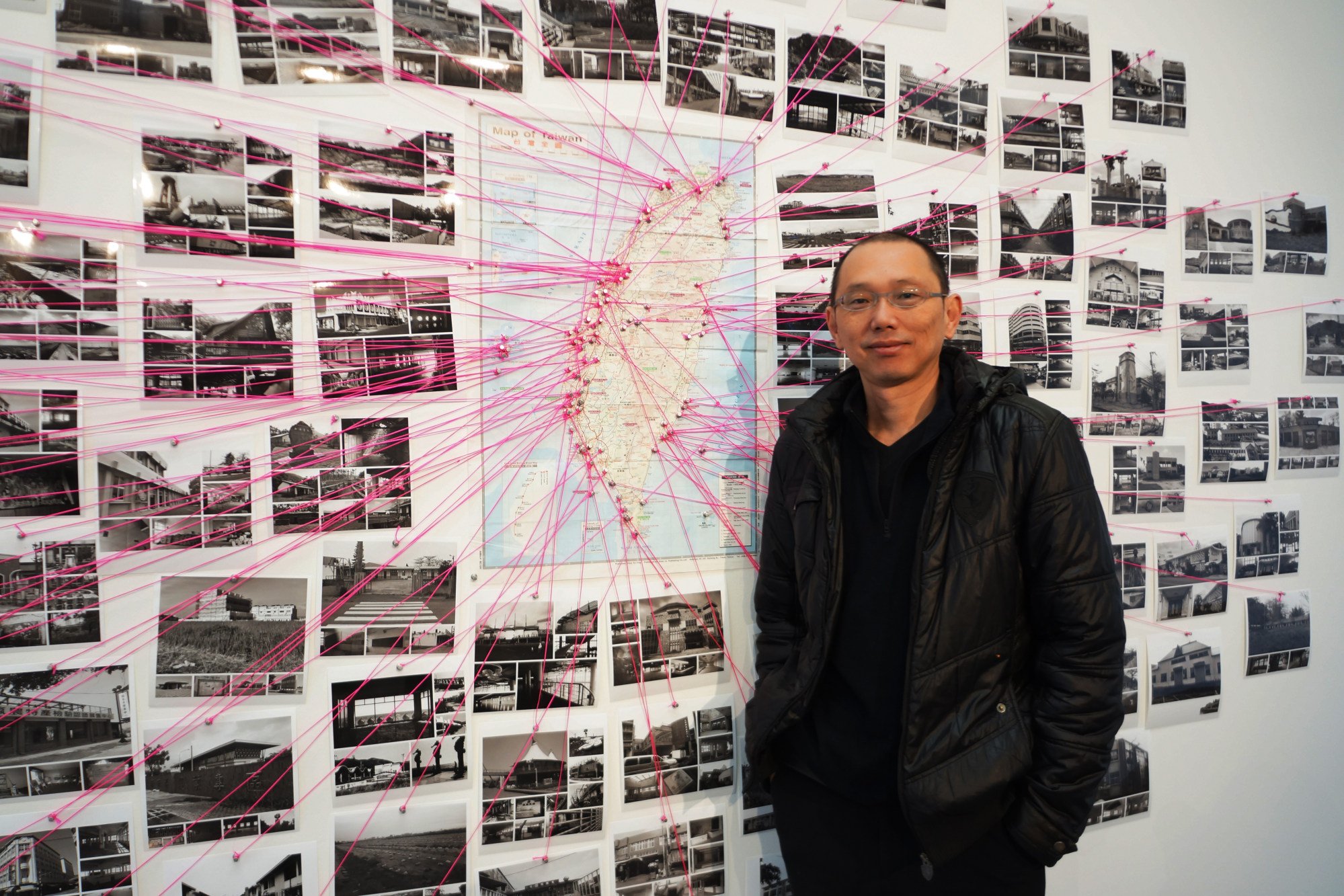

The “mosquito halls” on which his Vancouver exhibition focuses are convention centres, sports facilities, schools and other public buildings built between the 1970s and 2010s that were abandoned for a variety of reasons. Many of the schools, for example, were closed because of Taiwan’s persistently low birth rate.

The structures chronicled in the exhibition of black-and-white photographs include the Taiwan Pavilion, which debuted at the Expo 2010 Shanghai China before being dismantled and rebuilt in Hsinchu County, northwest Taiwan.

It is a dramatic glass-box structure housing a giant spherical lantern that has gone dark since the site closed permanently. The caption on his photograph of it says it cost NT$1.4 billion (US$40 million) to build.

Another photograph is of the Zhulu Cultural Performance Centre in Chiayi County, southwest Taiwan. It has a web-like roof that leaves the building exposed to the elements, and as a result a pool of water has formed on the ground.

Construction of the building began in 2014 but was never completed, after NT$70 million had been spent on it.

Over the years, Yao has asked his students in Taipei to help identify buildings by going through government websites that list public property. He has also encouraged them to speak to parents, friends, the local police and politicians in their hometowns to obtain background information about sites.

The exercise was also meant to foster a sense of local identity for the students, many of whom were not from Taipei, and to help them understand the economic disparity between different regions.

Together with Lost Society Document, an organisation formed by his students, and curator and documentarian Sandy Lo Hsiu-chih, Yao has published eight books about these sites.

He has sent them all to the Taiwanese government, the national auditor and every legislator and media outlet. “When the TV and newspaper reporters interviewed me, I asked the government to release these buildings for NGOs, artists, children, elderly people and the healthcare sector to use,” he says.

We need to talk about the history and memory of these places so people will not forget them

The documentary, which is over 10 minutes long, brings together a former tenant and employee who lived above the restaurant and a young Chinatown activist who is keen to educate the public about the importance of Gain Wah and drum up interest in revitalising the space.

The “Mirage” exhibition also features a map of Vancouver on which visitors are encouraged to pinpoint the locations of unused buildings they know of.

Space is a hot-button issue in Vancouver, with the cost of housing skyrocketing in recent decades and the city moving away from building single-family homes in favour of high-rise condominiums to house its growing population.

While in Vancouver, Yao went on a photo walk with a group of local amateur and professional photographers, exploring some abandoned buildings.

Museum of Vancouver staff, including Fong, gave historical context to the places they visited, which included a short stretch of railway used to ferry passengers during the 2010 Winter Olympics that is now rusted, with wild flowers growing between the rails.

“In Taiwan, we would use a site like this to do contemporary performance art, theatre or singing,” Yao says of the section of track and elevated platform alongside.

“We need to talk about the history and memory of these places so people will not forget them. Our government likes to erase the memories and that’s bad, because they are evidence of our existence,” he adds.

“Mirage: Disused Public Property in Taiwan”, Museum of Vancouver, 1100 Chestnut Street, Vancouver, Canada. For daily opening hours visit museumofvancouver.ca