In her introduction to Contact: Art and the Pull of Print, Jennifer L. Roberts wants you to know what the book is not about as much as what it is. One term, she explains, won’t be mentioned past this very deliberate point of omission: “reproduction” and its various associated terms—“replication,” or, even worse, “repetition”—are straight-up forbidden, starting now.

It’s a defensive posture to prove a point: Roberts, Faust professor of the humanities, is invested in the medium as a space for creative ingenuity, where its unique demands and properties converge in an art form entirely its own. A consideration of its replicative uses is an overworn path she won’t be taking anywhere in these nearly 200 pages, she says, and thank heavens for that. It’s probably too much to say that Contact breaks new ground on printmaking as a much-overlooked art form, but it does, with sharply exclusive intent, concern itself with the medium’s higher purpose as a field of inquiry, possibility, and imaginative verve.

In her advocacy, Roberts seems to take personally the dismissive air that’s often attended the discipline (“just prints,” she points out, is the consistently offhand malignment that sticks most in her craw). And make no mistake: Contact is an argument, and a thorough one, by a uniquely informed and curious mind. It just might not be an argument that most in the art world thought necessary to have.

Roberts’s focus is on contemporary prints, mid-twentieth-century and beyond, when movements like Conceptualism and Pop helped unlock deeper and more self-reflective works about the medium itself, after centuries of—ahem—mostly straight reproduction. For process nerds (like me), Contact puts the pieces together, weaving disparate threads of printing’s insidious, under-the-radar stamp on contemporary art.

I knew, for example, about David Hammons pressing his margarine-swathed self onto heavy paper, the resulting stain of facial feature and clothing the basis of his “Body Print” series of the 1970s; and I’d long marveled at Robert Rauschenberg’s “Hoarfrost Editions” series, the product of running soggy, crushed pages of newspapers and magazines through a press with results more happenstance than intentional.

Roberts spends time on these works in the opening chapter, “Pressure,” a term she explores in literal and allegorical ways. I’ll say I don’t really recall whether I thought of either of them (or Andy Warhol’s serial works of celebrities or car crashes or electric chairs, duh) as prints so much as, well, art. Therein lies the issue, I suppose. In the art world, we have a whole language for exalted practices like painting; when someone says “painterly”—that is, how a particular artist tracks impasto over canvas or paper (or whatever), as personal and unique as a signature—we know exactly what he or she means.

Has anyone ever used the term “printerly?” I’m betting not. A medium so defined by its technical parameters—a print has to be, well, printed; a painting is whatever the artist wants to shove around a canvas, by whatever means—inevitably lends itself to a technical consideration. That a mechanical tool might be seen in the same terms as a brush, or a pen, or a sculptor’s hand was no doubt a stretch for many, and for a long time.

But the same was said of photography, the mass proliferation of which in the early twentieth century prompted the German philosopher Walter Benjamin to write, in his seminal 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” that (to mercilessly paraphrase) the camera’s ability to create a perfect facsimile freed art to be more broadly interpretive and subjective, and to consider motives beyond mere representation. In other words, it threw gasoline in the smoldering embers of Impressionism and helped fuel an explosion of free-flowing experimentation—of which photography itself is undeniably part.

Photography, of course, evolved past the utilitarian, and quickly; it’s now in the soup of every art movement, conceptual or otherwise. Its reproductive function didn’t limit its potential, and eventually, its perception; like any medium, limitations are almost always external, not internal, and blowing them to bits is one of the most satisfying things an artist can do.

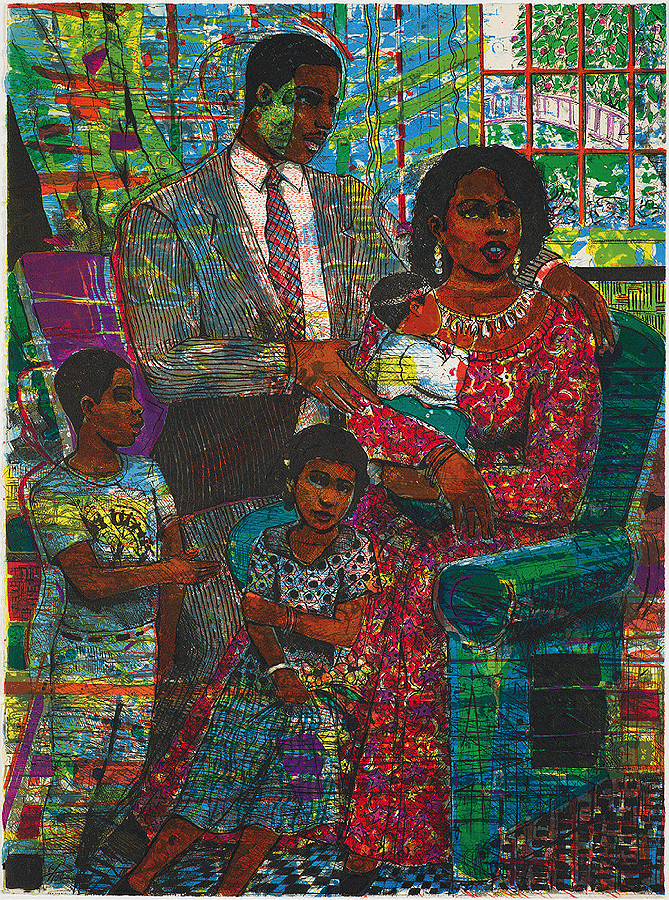

Unity (1995), an offset lithograph on white wove paper. | ©Estate of Louis Delsarte. Photo: Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

Printmaking has all this potential, much evidence of seizing it, but much less recognition (Jasper Johns, quoted in chapter two, says printmaking “makes your mind work in a different way,” and that it has elements that “are interesting in themselves”). Why? In that second chapter, “Reversal,” Roberts begins with a critical point: Printing, from its very beginning—way before photography—was maybe the essential seedling of modernity, giving information to the masses, wresting control from the elites (Martin Luther’s Bible comes to mind), and making possible widespread literacy and everything that entailed.

Printing was a key tool of the Enlightenment, making available text and images that brought about the first real era of broader public education and knowledge. Among the things it furnished to the public at large was art, in reproduction; aesthetics had never been so democratic. So, the class associations of printing are in its DNA. Prints were often made for mass markets and mass distribution, cheapening them not only as commodities but as art. One can see how, in the era of Conceptual Art in the 1960s, printing would have its own anti-capitalist value. Conceptualism was, among other things, a refutation to an art market run amok; it happily embraced cheap materials or, as the art critic Lucy Lippard had it, the “dematerialization” of art as object entirely, with performance or “happenings” as tableau.

And yet, in its subtleties, its own limitations, there is magic. In “Reversal,” Roberts speculates on a 1642 etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, The Raising of Lazarus; she and it remind us that printing is backwards: The impression is the finished product; the labored-upon surface, in this case, copper plate, is not only meticulously and masterfully scratched into being by the artist, but as a mirror image. Rembrandt was criticized for the piece because in the print, Christ revives Lazarus with his left hand; divination was meant to issue from the right. And on the plate, it does, but the print…well. It’s a pretzel of process that calls to mind all kinds of Benjamin-esque notions of authenticity—where the plate, not the print, is the vessel of artistic aura, bearing the marks of the artist’s hand and intent.

But I digress, not least because Contact is an invitation to digression. Across its six chapters, tangents abound, along with countless spectacular illustrations; Roberts deals expertly with the deeper meaning of making something meant to be made again. And she excels in tying historical and technical fact to philosophical, conceptual, and even poetic intent, and grapples gamely with the deeper meaning of making something meant to be made again. Ideas about the disavowal of source, or the dilution of and challenge to conventional notions of authenticity, are intellectually rich and provocative.

I will say, though, that I often found myself lost in the exhaustive detail of the medium’s intensive mechanics. In the third chapter, “Separation,” the physical reality of four-color printing—requiring images to run through a press multiple times to add all the desired hues—engages the reader with its conceptual frame for formal intentions: Julie Nehretu’s abstract Entropia (review), 2004, becomes an avatar for the literal pulling apart of an image to reconstruct it as whole. Stirringly, Mark Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge, 2023, a 400-foot-long piece recently installed in the circular upper galleries of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., charges notions of appropriation and reproduction with the politics of representation and oppression: the work is a radical deconstruction of the French painter Paul Philippoteaux’s monumental cyclorama painting of the Battle of Gettysburg from 1883—and, Roberts points out, a print. To make it, Bradford downloaded portions of the original from the internet, blew it up into strained and pixelated view, and tore it to shreds, fracturing the violently heroic narrative into one infinitely more complex, chaotic, and unresolved. As the shreds of paper dangling from the surface make clear, print did that—and as testament to incomplete histories that tend to favor victors, it’s hard to see another medium that could.

But the text bogs down in dense technical detail that I’m not sure I can even try to reproduce here; even after reading it twice, I still don’t think I quite get it, and I wonder if I really need to. It made me wonder a little whether the book is for enthusiasts, or printmakers themselves, a decidedly smaller audience to say the least.

Roberts began the book by explaining that each of the chapters started life as an online lecture, delivered in 2021 during the pandemic from her closet-sized office; in assembling them into the book, she made the decision not to harden her prose into more academic language, but to keep the conversational tone of the lectures themselves.

That shines through in spots and is clouded in others. This is ultimately an expert’s guide with several bones thrown to the enthusiast, when I think I’d prefer it the other way around.

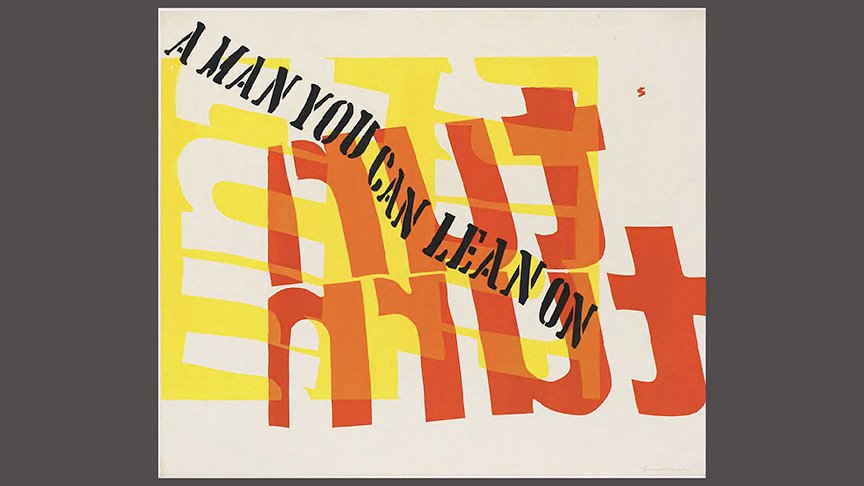

In chapter four, “Strain,” devoted almost exclusively to screen printing, Roberts moves briskly from the medium’s genesis of printmaking at its most pervasive (screen printing was, and is, the domain of advertising and mass media like posters, billboards, T-shirts, and so on) to artists like Warhol, who used exactly those qualities to make an art predicated on conspicuous consumption and the imperfections inherent in a medium expected to make infinite, identical copies. She cites National Velvet, Warhol’s incomplete grid of the repeated image of Elizabeth Taylor, showing the physical tracks of the printing process in the subtle variations image to image; it’s a terrific, mind-pleasing example of being, well, printerly. But the mechanics of screen printing befuddle, and there’s a lot of it. It made my reading selective, not fluid. Chapter five in particular, “Interference,” really started to lose me; it felt very far away from the meaty social implications that compel other parts of the book.

But the final chapter, “Alienation,” is among the richest; here, Roberts departs largely from technical discussion and allows herself the free-flowing consideration of a time- and labor-intensive medium’s role amid the intense, immediate, and constant torrents of image and information that define the digital era. She dwells long on the work of Christine Baumgartner, a German artist who works in woodcut printing, among the oldest and most laborious processes in any medium, let alone printmaking. Baumgartner’s images, painstakingly produced by hand and at massive scale (her blocks, usually sheets of plywood, are both too big and too soft to run through a press), are confounding, inky shadows of photographic realism in soft black and white. They take weeks or months to render an image that could be captured in an instant and rendered via any digital editing program in minutes.

So, why? This, perhaps, is the most valuable insight of all that echoes throughout the book and beyond: Baumgartner’s painstaking efforts engage slow, deep examination—a nearly lost art in itself—that prompt “insights for contemporary life that are not available otherwise,” Roberts writes. That’s putting it mildly. In the physical labor of print, revelation awaits in the richness of languorous looking, an experience eroding in front of our eyes.