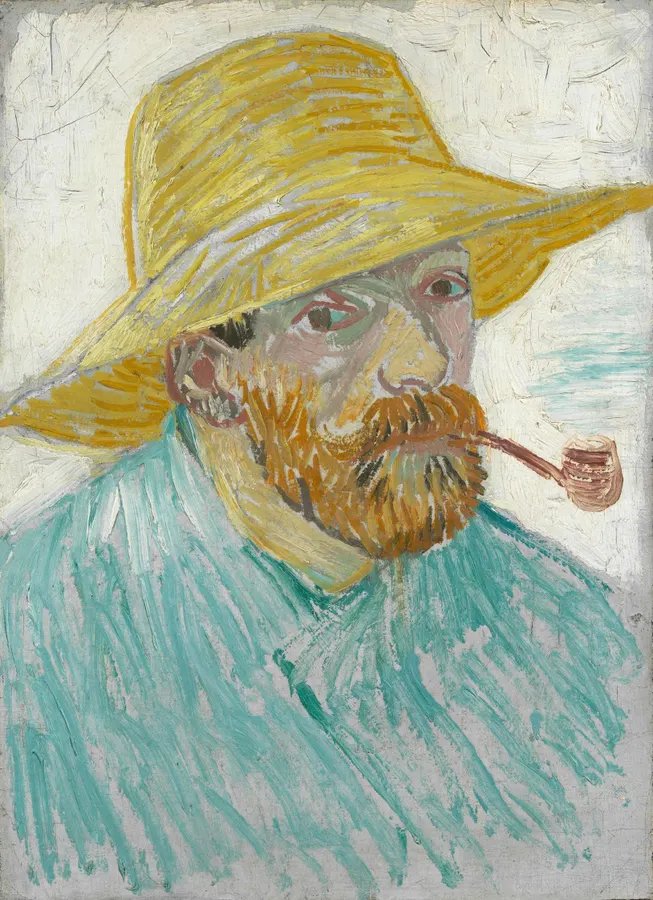

Vincent van Gogh, Self -Portrait with Pipe and Straw Hat , 1887. Oil on canvas, 41.9 cm x 30.1 cm.

© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

At the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last brings to life one of the most intimate, revealing chapters of Vincent van Gogh’s time in Arles. Following its debut at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the exhibition reunites for the first time, a substantial grouping of the 26 portraits Van Gogh painted of the Roulin family: Joseph, Augustine, and their children Armand, Camille, and baby Marcelle. The result is a moving, tightly focused showcase that illuminates the artist’s evolving emotional world, his breakthroughs in portraiture, and the profound personal bond that sustained him during one of the most turbulent periods of his life.

‘Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last’ at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photograph by Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

A friendship forged in Arles

The story begins in the summer of 1888, when Van Gogh had settled in Arles seeking the bright sun and vivid colors of Provence. He envisioned building a community of artists there, yet the reality was loneliness, financial instability, and a continual struggle with his mental health. Amid this challenging backdrop, a friendship emerged that would anchor him: his relationship with Joseph Roulin, the Post Master at Arles train station.

Roulin was solidly built, with a flowing beard and wise, penetrating gaze, and he became not only a willing sitter but also a confidant to the increasingly vulnerable painter. His wife Augustine and their children embraced Van Gogh as well, offering a sense of warmth and stability at a time when the artist desperately needed both. This extraordinary connection forms the emotional heart of the Amsterdam exhibition.

Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photograph © Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

An enigmatic chair at the center of it all

The exhibition opens with a subtle yet deeply affecting moment. Van Gogh’s self-portrait in a blue smock and yellow straw hat hangs beside a lonely willow-frame chair–a humble but electrifying presence. Visitors soon learn this is the very chair from Van Gogh’s Arles studio, the chair on which the Roulin family sat as they posed for him, and the same chair famously depicted in his paintings. Long overlooked in storage and too fragile to travel to Boston, it is being shown for the first time.

The quiet authority of the chair–so often a sentinel in Van Gogh’s visual world–announces itself the moment one steps into the exhibition rooms. Placed at the threshold, the humble seat from his Arles studio becomes less an object than an invocation, a timber echo of the artist’s hand and solitude.

In the Van Gogh Museum’s permanent exhibition visitors can see the artists’s cherished vision of his Arles bedroom, where a plain wooden chair keeps vigil beside the neatly made bed: an emblem of domestic simplicity, yet charged with the presence of its absent occupant. Van Gogh’s use of the chair as a pictorial and metaphorical motif continues in Van Gogh and the Roulins.

Gauguin, Van Gogh’s mercurial companion during those turbulent months in Arles, appears at the exhibition’s opening in a small portrait gazing across at the chair from his Arles studio, as though continuing an old, unresolved conversation. Further into the exhibition visitors encounter Gauguin’s Chair (1888), its red and green hues smouldering with unease, the candle perched upon it trembling like a nervous heartbeat beside two casually placed books.

In Van Gogh and the Roulins, the Arles studio chair greets visitors almost as an apparition, part relic, part portrait. It stands for the artist himself, but also for the constellation of sitters who shaped his days in Arles: Gauguin, the devoted Roulins, and all those who left their trace in the hollow of its seat. Through this simple wooden form, their presence flickers back to life.

Curator Nienke Bakker explained to me when we met at the museum: “At some point we thought we should put it in the exhibition. Of course, it makes sense. But it couldn’t travel to Boston because it’s so fragile. Really, it’s the perfect moment. It has been waiting for this.”

It feels poignant to have the chair positioned next to Van Gogh’s self-portrait at the start of the exhibition, as if Vincent’s ghost is in the room. It also serves to give a sense of the Roulins family sitting for Van Gogh on the chair.

Bakker continues: “I really wanted that visitors walking into the exhibition would see the first portrait of Monsieur Roulins. Our designer said we should put the chair right at the beginning, as if you enter into the studio and you see his chair. I wanted to put the friends (Vincent and Joseph) close together with the chair in the middle. It makes it very tangible. Also because Vincent was probably the first in his studio to sit in this chair, and Roulin was one of the sitters posing on the chair.”

Positioned next to Van Gogh’s self-portrait, the chair becomes a quiet stand-in for the artist himself, as though Vincent’s presence lingers just beyond the frame.

This staging becomes a perfect prelude to the first major portrait on view: Joseph Roulin seated in his navy blue uniform, rendered with bold strokes and an almost sculptural beard. Displayed opposite its real-world counterpart, the chair creates an intimate bridge between object, sitter, and painter: one of several curatorial decisions that give this exhibition its emotional weight.

Vincent van Gogh, Postman Joseph Roulin, 1888. Oil on canvas, 81.3 × 65.4 cm. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Robert Treat Paine. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All Rights Reserved.

Understanding Joseph Roulin

Van Gogh painted Joseph repeatedly, captivated by his dignity, steadiness, and rich color palette of blue and gold offered by his uniform. In letters to his brother Theo, he likened Roulin’s thoughtful nature to that of Socrates, a comparison that becomes visually persuasive when standing before these works.

So how did Joseph meet Van Gogh? Bakker explains: “He became friends with Roulin while he was sitting for his portrait. They probably met in the café (in Arles). Van Gogh was living there – he rented a room upstairs from the café before he moved to the Yellow House. They would also have run into each at the station, where Joseph was working as postmaster, and Van Gogh would go there to send paintings to his brother in Paris, and also to pick up shipments of canvas and paint.”

Their friendship grew naturally. Before moving into The Yellow House in Arles, Van Gogh lived above a café where the two likely first met. Their paths crossed at the station as well where Vincent would send canvases to his brother Theo and collect deliveries of paint and canvas. Over time, Roulin became more than a model, he became an emotional anchor.

Vincent van Gogh, The Yellow House (The Street) , 1888. Oil on canvas, 72 cm x 91.5 cm

© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Gauguin and a telling contrast

The exhibition subtly contrasts the steadfast loyalty of the Roulin family with the volatility of Van Gogh’s relationship with Paul Gauguin. Across from one early portrait of Joseph hangs Gauguin’s head rendered in acidic green–painted shortly before the two artists’ quarrels escalated. Gauguin fled Arles after Van Gogh’s infamous breakdown when he famously cut off his ear and presented it to a local prostitute before being admitted to hospital, yet the Roulins continued to support him with their unconditional friendship. Augustine visited Vincent in hospital, and Joseph sent letters of encouragement. Their kindness left a lasting imprint that Van Gogh would echo in his works.

In a letter to Theo from April 1889, Van Gogh described Roulin’s compassionate presence: “While Roulin isn’t exactly old enough to be like a Father to me, all the same he has silent solemnities and tenderness for me like an old soldier would have for a young one.” This tenderness permeates the portraits, granting them a warmth that transcends their sometimes feverish colors.

‘Gaugin’s Chair’ by Vincent van Gogh at Van Gogh Museum. Photograph by Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

Augustine as La Berceuse

One of the exhibition’s most compelling sequences is the series of portraits of Augustine Roulin, whom Van Gogh painted as La Berceuse (The Lullaby). In these works, Augustine appears serene and maternal, gently holding a rope used to rock a cradle just outside the frame. Van Gogh imagined the paintings hung in a sailor’s cabin so that fishermen at sea might feel comforted, “reminded of their own lullabies.”

These portraits reveal Van Gogh at his most experimental. Inspired by Dahlias from his Mother’s garden and Japanese woodblock prints from the collection he shared with Theo, he placed Augustine against bold, decorative floral backgrounds. The repeated motif morphs throughout the series–from representational blooms to dynamic abstractions–mirroring the psychological arc of his time in Arles and then in hospital. The juxtaposition of Augustine’s calm demeanor with the vibrating backdrop reflects Van Gogh’s desire to elevate everyday domestic life into something symbolically powerful.

Portrait of Augustine Roulin, ‘Van Gogh and the Roulins. Together Again at Last’ at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photograph © Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

A deeper dialogue with art history

Bakker and co-curator Katie Hanson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, weave art-historical context into the exhibition with precision. Sightlines connect Van Gogh’s portraits to works by Rembrandt, Frans Hals, Honoré Daumier, and Gauguin, underscoring the artists he studied intensely. Rembrandt’s empathy, Daumier’s compassion for working people, and Hals’s brisk brushwork all echo in Van Gogh’s portrayals of the Roulins, not as derivative influences, but as living artistic conversations.

This thoughtful contextualization reveals Van Gogh not as a solitary genius but as an artist deeply aware of, even in dialogue with, his predecessors.

Portraits of Baby Roulins in ‘Van Gogh and the Roulins’ at Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. Photograph by Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

A family reunited

The reunion of 14 Roulin Family portraits in one space is nothing short of revelatory. Armand appears serious and introspective; Camille’s youthful, mischievous spark shines through, and baby Marcelle radiates innocence. Collectively, they read like chapters of a family saga, one in which Van Gogh himself is both narrator and participant.

For visitors accustomed to the blazing yellows of Sunflowers or the cosmic swirl of Starry Night, the Roulin portraits offer something quieter but equally profound. They reveal Van Gogh’s belief that ordinary working people could embody universal emotions and archetypes. By painting them again and again, he was refining not just his technique but his understanding of human connection.

Vincent van Gogh ‘Madame Augustine Roulin and Baby Marcelle’, ‘Van Gogh and The Roulins’. Photograph © Lee Sharrock

© Lee Sharrock

Van Gogh and the Roulins is elegantly curated, deeply researched, and emotionally resonant. It reveals Van Gogh’s humanity through the people who offered him friendship, stability, and kindness at a time when he needed them most. More than an exhibition of portraits, it is a portrait of a friendship that shaped an artist’s life and helped define an era of his work.

In reuniting these canvases, the Van Gogh Museum invites us into the painter’s inner circle, reminding us that even amid personal turmoil, Van Gogh found solace in the company of a humble postman’s family. Their presence sustained him. Their portraits endure.

Van Gogh and the Roulins is on view at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, until 11th January, 2026.